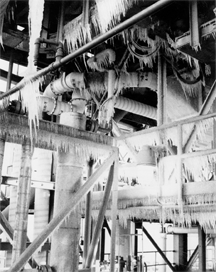

Ice on the launch pad on January 28, 1986, the day of the last Challenger Launch (STS-51-L). The unusually cold weather was well beyond the tolerances for which the rubber seals of the solid rocket boosters were approved, and it most likely caused the O-ring failure that led to the Challenger loss. Groupthink probably provides a solid explanation for the flawed launch decision, but it can do much more. The string of decisions that led to the design of the space shuttle itself might also have benefited from scrutiny from the perspective of groupthink. Even more important, though, is the organizational design of NASA. There was a belief both inside NASA and out that it was an elite organization that always got things right. That belief is one of the fundamental characteristics that makes groups and organizations susceptible to groupthink. Only after the loss of Challenger did the question of the design of NASA come into focus. See, for example, Howard S. Schwartz, Narcissistic Process and Corporate Decay, New York University Press, 1992. (Order from Amazon.com) Photo by Michael Hahn, courtesy U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Design is the articulation of intent to achieve a goal, including plans for executing that intention. We're engaged in design whenever we devise products, services, procedures, tests, policies, legislation, campaigns — just about anything in the modern knowledge-oriented workplace. And when we design, we risk error. Our design might not achieve all we hoped, or it might not achieve the goal at all. Or we might discover that the goal we were aiming for isn't what we actually wanted. So much can go wrong that attaining even a measured success sometimes feels thrilling.

Design errors are more common than we imagine. When a system produces disappointing results, we cannot always distinguish design errors from user errors or implementation errors. And we don't always know whether the system was being used in an environment for which it was designed. That's why we sometimes mistakenly attribute system failures to something other than design error, even when design errors played a role.

Because we usually use the term error for undesirable outcomes, the language we use to describe design errors carries connotations that limit our thinking. For this discussion, we use error to mean merely unintended as opposed to unintended and unfavorable. With this in mind, when a design "goes wrong" we mean that it didn't achieve the goal, or that we discovered an even more desirable goal. We must therefore classify as design errors those exciting surprises that bring welcome results. Typically, we take credit for these as if we intended them, but their sources are often simple design errors.

The Design errors are more

common than we imaginekind of design errors I find most fascinating are those that arise from the way humans think and interact. Let's begin with one of the most famous of group biases, groupthink.

Groupthink happens when groups fail to consider a broad enough range of alternatives, risks, interpretations, or possibilities. Groups are at elevated risk of groupthink if they aren't diverse enough, or lack sufficient breadth of experience, or feel infallible, or want to preserve their elite status, or have an excessive desire for order.

For example, if an elite review team is pressed for time and must review two designs — one by an elite development team, and one by a less accomplished team, it might decide to do a less-than-thorough job on the work of the elite development team so as to make time for careful review of the work of the less-accomplished development team. Because the review team values its reputation for getting work done on time, and because it feels an affinity for the elite developers, an error in the elite developers' work can squeeze through. That might not be a bad thing, of course. Some design errors produce favorable outcomes. Such beneficial errors are rare, but we ought not dismiss the possibility out of hand.

We'll continue next time with an examination of more group biases. Next in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrendPtoGuFOkTSMQOzxner@ChacEgGqaylUnkmwIkkwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Problem Solving and Creativity:

Choices for Widening Choices

Choices for Widening Choices- Choosing is easy when you don't have much to choose from. That's one reason why groups sometimes don't

recognize all the possibilities — they're happiest when choosing is easy. When we notice this

happening, what can we do about it?

Intentionally Unintentional Learning

Intentionally Unintentional Learning- Intentional learning is learning we undertake by choice, usually with specific goals. When we're open

to learning not only from those goals, but also from whatever we happen upon, what we learn can have

far greater impact.

Virtual Brainstorming: II

Virtual Brainstorming: II- When virtual teams must brainstorm, they try to do so virtually. But brainstorming isn't just another

meeting. There's a real risk that virtual brainstorms might produce inadequate results. Here's Part

II of some suggestions for reducing the risk.

Newtonian Blind Alleys: I

Newtonian Blind Alleys: I- When we decide how to allocate organizational resources, we make assumptions about how the world works.

Often outside our awareness, the thinking of Sir Isaac Newton influences our assumptions. And sometimes

they lead us into blind alleys. Universality is one example.

On Working Breaks in Meetings

On Working Breaks in Meetings- When we convene a meeting to work a problem, we sometimes find that progress is stalled. Taking a break

to allow a subgroup to work part of the problem can be key to finding simple, elegant solutions rapidly.

Choosing the subgroup is only the first step.

See also Problem Solving and Creativity and Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming April 24: Antipatterns for Time-Constrained Communication: 1

Coming April 24: Antipatterns for Time-Constrained Communication: 1- Knowing how to recognize just a few patterns that can lead to miscommunication can be helpful in reducing the incidence of problems. Here is Part 1 of a collection of communication antipatterns that arise in technical communication under time pressure. Available here and by RSS on April 24.

And on May 1: Antipatterns for Time-Constrained Communication: 2

And on May 1: Antipatterns for Time-Constrained Communication: 2- Recognizing just a few patterns that can lead to miscommunication can reduce the incidence of problems. Here is Part 2 of a collection of antipatterns that arise in technical communication under time pressure, emphasizing those that depend on content. Available here and by RSS on May 1.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrendPtoGuFOkTSMQOzxner@ChacEgGqaylUnkmwIkkwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrendPtoGuFOkTSMQOzxner@ChacEgGqaylUnkmwIkkwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!