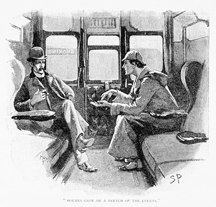

Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson, in an illustration by Sidney Paget, captioned "Holmes gave me a sketch of the events." The illustration was originally published in 1892 in The Strand magazine to accompany a story called The Adventure of Silver Blaze by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It is in this story that the following dialog occurs:

Gregory (Scotland Yard detective): "Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?"

Holmes: "To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time."

Gregory: "The dog did nothing in the night-time."

Holmes: "That was the curious incident."

From this, Holmes concludes that the dog's master was the villain. This is an example of what I here call abductive reasoning.

Original book illustration, courtesy Wikimedia.

In Part I and Part II of this exploration of contributions to pre-decision discussions, I examined how we use facts and emotions in discussion contributions. We can think of facts and emotions as the raw materials of the discussion. Reasoning is a tool for combining the raw materials into a comprehensible structure. So in this part I examine how the three different kinds of reasoning can build new components that help us find paths to final decisions.

Three forms of reasoning are available for use in pre-decision discussions. Most uses of reasoning in organizational settings are informal, but even in informal reasoning there are some refining attributes. Those attributes distinguish the three forms of reasoning.

- Deductive reasoning

- We use deductive reasoning to proceed from premises to conclusions in a sequence of steps, each step following from its predecessors by implication. Deductive reasoning provides strong validation for its conclusion. For example, if we know that testing is the only way to be certain that our software application works as intended, and we also know that we haven't tested our software application in a given release of an operating system, then it follows that we don't know for certain whether our software application works in that release of the operating system. The software might work, or it might not work, but we can be certain that we don't know for certain.

- Deductive reasoning based on validated facts and evidence provides a validated conclusion. That is its appeal. But rarely do we have validated facts and evidence, because we rarely have the time and resources required for validating those facts and evidence.

- Inductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning also proceeds from premises to a conclusion, but it establishes the conclusion as a generalization of the premises. When the basis for the generalization is data regarding large numbers of examples, the generalization is statistical. When the basis for the generalization is a limited number of cases deemed typical of a large class, the generalization is anecdotal. Neither kind of generalization leads with certainty to a valid conclusion. For this reason, inductive reasoning is less likely to provide strong validation for the conclusion.

- But inductive reasoning is still useful. Continuing with our software example, suppose we know that the operating system release in question is a minor update of the previous release, and that our software worked well in four previous minor updates. Reasoning inductively, we then have reason to believe that the software will work in this new minor release. It might work, or it might not work. We don't know for certain, but based on past experience, we believe there is a strong chance that the software will work.

- Abductive reasoning

- Abductive reasoning is neither deductive nor inductive, but, in a weird way, it can be both. Distinguishing abductive reasoning and deductive reasoning can be difficult, because what Sherlock Holmes (Arthur Conan Doyle actually) calls deductive is in the modern terminology, abductive.

- When we're Reasoning is a tool for combining the

raw materials of a discussion — facts

and emotion — into a comprehensible

structure that helps us

find paths to decisionsreasoning abductively, we begin by gathering data about the situation. We then formulate an explanation. That is, we apply principles that we believe pertain to that situation to provide an explanation for what we observe about the situation. - To illustrate, consider yet another extension of the software example. Suppose we actually test our software on 22 machines running the minor update of the operating system. And further suppose that on three of the 22 machines, the software fails. Examining all 22 machines, we notice that the three that failed were also running an old version of a popular word processing program. The machines on which our software operated correctly were running an updated version of that word processing program. Using abductive reasoning we suggest that an unanticipated interaction could be occurring between our software and the word processor. Engineers then investigate further, and they do discover the problem and install a repair.

Using deductive reasoning, we find a conclusion by starting with premises, and creating a chain of implications connecting them to the conclusion. Using inductive reasoning we create a generalization from the premises to reach a highly plausible conclusion. And using abductive reasoning we create an explanation that fits all available observations. Noticing the kinds of reasoning in use in your organization can help you reach more solid conclusions more rapidly. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Do you spend your days scurrying from meeting to meeting? Do you ever wonder if all these meetings are really necessary? (They aren't) Or whether there isn't some better way to get this work done? (There is) Read 101 Tips for Effective Meetings to learn how to make meetings much more productive and less stressful — and a lot more rare. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Conflict Management:

How to Avoid Responsibility

How to Avoid Responsibility- Taking responsibility and a willingness to be held accountable are the hallmarks of either a rising

star in a high-performance organization, or a naïve fool in a low-performance organization. Either

way, you must know the more popular techniques for avoiding responsibility.

Covert Bullying

Covert Bullying- The workplace bully is a tragically familiar figure to many. Bullying is costly to organizations, and

painful to everyone within them — especially targets. But the situation is worse than many realize,

because much bullying is covert. Here are some of the methods of covert bullies.

On Differences and Disagreements

On Differences and Disagreements- When we disagree, it helps to remember that our differences often seem more marked than they really

are. Here are some hints for finding a path back to agreement.

Quasi-Narcissistic Quasi-Subordinates

Quasi-Narcissistic Quasi-Subordinates- One troublesome kind of workplace collaboration includes those that combine people of varied professions

and ranks for a specific short-term mission. Many work well, but when one of the group members displays

quasi-narcissistic behaviors, trouble looms.

Overt Verbal Abuse at Work

Overt Verbal Abuse at Work- Verbal abuse in the workplace involves using written or spoken language to disparage, to disadvantage,

or to otherwise harm others. Perpetrators tend to favor tactics that they can subsequently deny having

used to harm anyone.

See also Conflict Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!