The Costanza Matrix

Seinfeld, a TV series that first ran from 1989 to 1998 in the United States (and will likely run for decades more) was famous as a "show about nothing." More accurately, perhaps, it was a show about life. It has become the source of a genre of Web sites, books, and miscellaneous whatnot with the general theme "What Seinfeld Teaches Us about Life." One valuable idea that I — and many others — drew from Episode 102 appears in a line spoken by the famous ne'er-do-well character "George Costanza," who says, "…it's not a lie…if you believe it."

Whether he's correct or not, it's apparent that "George" does believe what he's saying, and therefore, if his claim is correct, he's not lying. But that's obvious. Less obvious: if the statement is incorrect, is he lying?

This is a nontrivial question. In the United States, substantiating a charge of fraud requires that five specific conditions be met, one of which is that the defendant must have knowingly made a false statement.

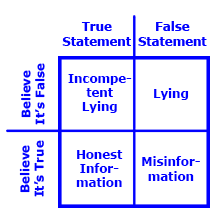

So I decided to examine the connection between statement validity and the speaker's belief. The result is what might be called "The Costanza Matrix." As a legal tool, it isn't worth much, but in the workplace it can help sort out ethical questions when someone makes a false statement.

The Costanza matrix is a two-by-two matrix whose axes might be described as Statement Truth and Speaker's Belief, which are, respectively, the degree of truth of the statement, and the degree to which the speaker believes it. Here are the four cells of this matrix.

- Statement is true; Speaker believes it's true

- The speaker is honestly conveying valid information when the statement is true and the speaker believes it's true. I call this Honest Information.

- Statement is false; Speaker believes it's true

- The speaker The Costanza matrix is a two-by-two

matrix whose axes might be

described as Statement Truth

and Speaker's Beliefis making an honest error when the statement is false, but the speaker believes it's true, whether out of ignorance, stupidity, or having been misinformed. I call this Misinformation. This is the situation "George" was talking about: it's not a lie if you believe it. - Statement is false; Speaker believes it's false

- The speaker is dishonestly conveying disinformation, or is plainly lying, when the statement is false, and the speaker knows it's false. I call this Disinformation or Lying.

- Statement is true; Speaker believes it's false

- When the statement is true, but the speaker believes it's false, and intends to mislead, the speaker is lying, but incompetently so. I call this Incompetent Lying.

The possibly novel insight here is that when a speaker is making a true statement, it's nevertheless a lie if the speaker believes it to be false and intends to mislead — an incompetent lie, to be sure, but still a lie. One finer point: if the statement is true, but the speaker believes it's false and is mistaken about why he or she believes the statement is false, we might be underestimating the degree of incompetence, but the speaker is still lying incompetently. In any case, as "George" might say, if a statement is true, "it is a lie if you don't believe it." ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Ethics at Work:

Budget Shenanigans: Swaps

Budget Shenanigans: Swaps- When projects run over budget, managers face a temptation to use creative accounting to address the

problem. The budget swap is one technique for making ends meet. It distorts organizational data, and

it's just plain unethical.

When You Aren't Supposed to Say: III

When You Aren't Supposed to Say: III- Most of us have information that's "company confidential," or even more sensitive than that.

Sometimes people who want to know what we know try to suspend our ability to think critically. Here

are some of their techniques.

Devious Political Tactics: A Field Manual

Devious Political Tactics: A Field Manual- Some practitioners of workplace politics use an assortment of devious tactics to accomplish their ends.

Since most of us operate in a fairly straightforward manner, the devious among us gain unfair advantage.

Here are some of their techniques, and some suggestions for effective responses.

Extrasensory Deception: I

Extrasensory Deception: I- Negotiation skills are increasingly essential in problem-solving workplaces. When incentives are strong,

or pressure is high, deception is tempting. Here are some of the deceptions popular among negotiators.

Counterproductive Knowledge Work Behavior

Counterproductive Knowledge Work Behavior- With the emergence of knowledge-oriented workplaces, counterproductive work behavior is taking on new

forms that are rare or inherently impossible in workplaces where knowledge plays a less central role.

Here are some examples.

See also Ethics at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!