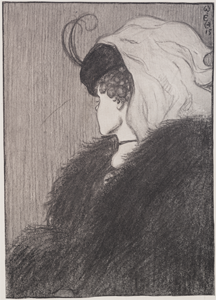

"My Wife and My Mother-in-Law", a famous optical illusion, appears in Puck, 78:2018 (1915 Nov. 6), p. 11. This optical illusion illustrates a visual ambiguity (as do many others). It reminds us that ambiguity in any context can be the result of how our own perceptual apparatus works, or even what state it is in. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Ambiguity is a delightful ingredient of poetry, art, and Life. But in the context of complicated technical collaborations, ambiguity can be an expensive hindrance. One could be forgiven for speculating that a long stretch of the road to failure is paved with ambiguity. Although success can depend on knowing how to recognize ambiguity, recognition is only a first step. We need to know how to resolve ambiguity, how to avoid it, and how to work with it when we can't resolve it or avoid it.

Distinguishing ambiguity and uncertainty

One commonOne could be forgiven for speculating

that a long stretch of the road to

failure is paved with ambiguity problem that arises in the context of dealing with ambiguity is confusion between ambiguity and uncertainty. A statement, a behavior, or a situation is ambiguous if it's consistent with two or more different interpretations or meanings. Uncertainty, on the other hand, is a situational condition that holds when aspects of that situation are unknown.

When we have available multiple possible interpretations of a swatch of information, then we're dealing with ambiguity. For example, if the work we require involves two different but similar technologies, A and B, we might know whether we should seek a specialist in A who is also conversant in B, or a specialist in B who is also conversant in A. In a case like that, we're dealing with ambiguity.

When we don't know what might occur, or how a situation might evolve, we're dealing with uncertainty. For example, if we need to hire a specialist to complete part of our project, but we don't know when we'll have approval for the necessary budgetary variance, we're dealing with uncertainty.

Confusion between uncertainty and ambiguity can arise when it's possible to assess probabilities of being correct for the various interpretations of ambiguous information. If we do that, then we're treating the different interpretations as if they were uncertainties. The risk here is that we might not actually have all interpretations in hand. So even though the assessed probabilities of all known interpretations sum to 100%, it's possible that another interpretation that we had never considered might turn out to be correct. Treating ambiguity as if it were uncertainty can then be an expensive error.

Kinds of ambiguity

The choice of effective tactics for resolving ambiguity depends on the nature of the ambiguity. Broadly speaking, there are two common types.

- Exclusive ambiguity

- In exclusive ambiguity, two or more interpretations differ because they are mutually exclusive in at least one respect. That is, although each interpretation is possible, ultimately only one can be valid. For example, consider a policy pronouncement defining the sales responsibilities for the components of the sales department of a company called FlowerCity. Suppose the statement reads, "Group A handles all sales of the Marigold product line, and Group B handles all sales of the Petunia product line." The statement is ambiguous relative to sales of product packages including combinations of Marigold and Petunia products. Either Group A or Group B will be responsible, but the policy statement is ambiguous with respect to this issue. The possible interpretations are exclusive of each other.

- Contradictory ambiguity

- In contradictory ambiguity, two or more interpretations differ in that one or both include elements that the other does not. Nevertheless, both interpretations could ultimately be valid. For example, when Nation A marshals military forces along its border with Nation B, the intelligence forces of Nation B might not be able to determine whether this deployment is offensive or defensive. When they observe that A's deployment includes missiles that have a range over 200 miles, they conclude that the deployment is offensive. But when they observe large inventories of anti-tank mines, they conclude that the deployment is mainly defensive. Ultimately, both interpretations are of course possible. Nation A might be preparing for both offensive and defensive strategies.

Choosing an ambiguity resolution strategy

Ambiguities sometimes resolve themselves as events unfold. For example, FlowerCity might discontinue combination sales. But resolving ambiguity intentionally often requires a proactive search for additional information — or some means of creating it. For example, an exclusive ambiguity might resolve upon emergence of information that rules out one of the possible interpretations. In our FlowerCity example, we might allocate all combination products to one sales department. For the international border clash example, we might task our intelligence gathering teams to search for more indicators of offensive or defensive weapons deployments, whichever seems most likely to produce clarifying results.

Last words

If an ambiguity isn't resolved, either by circumstances or intention, we must find ways to press forward with the ambiguity unresolved. In that circumstance, resilience strategies are most valuable, because they're more likely to survive resolution of the ambiguity in whatever way it resolves. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Projects never go quite as planned. We expect that, but we don't expect disaster. How can we get better at spotting disaster when there's still time to prevent it? How to Spot a Troubled Project Before the Trouble Starts is filled with tips for executives, senior managers, managers of project managers, and sponsors of projects in project-oriented organizations. It helps readers learn the subtle cues that indicate that a project is at risk for wreckage in time to do something about it. It's an ebook, but it's about 15% larger than "Who Moved My Cheese?" Just . Order Now! .

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Conflict Management:

What Insubordinate Nonsubordinates Want: II

What Insubordinate Nonsubordinates Want: II- When you're responsible for an organizational function, and someone not reporting to you won't recognize

your authority, or doesn't comply with policies you rightfully established, you have a hard time carrying

out your responsibilities. Why does this happen?

So You Want the Bullying to End: I

So You Want the Bullying to End: I- If you're the target of a workplace bully, you probably want the bullying to end. If you've ever been

the target of a workplace bully, you probably remember wanting it to end. But how it ends can be more

important than whether or when it ends.

Grace Under Fire: III

Grace Under Fire: III- When someone at work seems intent on making your work life a painful agony, you might experience fear,

anxiety, or stress that can lead to a loss of emotional control. Retaining composure is in that case

the key to survival.

Commenting on the Work of Others

Commenting on the Work of Others- Commenting on the work of others risks damaging relationships. It can make future collaboration more

difficult. To be safe when commenting about others' work, know the basic principles that distinguish

appropriate and inappropriate comments.

Rescheduling: the Politics of Choice

Rescheduling: the Politics of Choice- When the current project schedule no longer leads to acceptable results, we must reschedule. When we

reschedule, organizational politics can determine the choices we make. Those choices can make the difference

between success and a repeat of failure.

See also Conflict Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!