The waiter arrived with the cold drinks and started dealing them out. That usually meant that the sandwiches were close behind. The great service was one reason they all liked Mike's.

"Good question," said Kevin, pulling a pen from his pocket. "Napkin, James." James was closest to the napkin dispenser.

"Good question," said Kevin, pulling a pen from his pocket. "Napkin, James." James was closest to the napkin dispenser.

So he obliged. "Ah, the old back-of-the-napkin trick," said James. "Can't do it in your head, eh Kev?"

Marian loved watching these two go at each other. They were having fun.

Kevin was thinking, pen poised. "Marian, tell us one more time," he said.

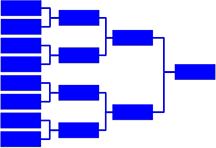

"OK," she said. "64 teams in the tournament. Single elimination. How many games total will they play?"

Kevin thought there was a trick. "So, 32 games in the first round, 16 in the second…like that?"

Before Marian could answer, James solved the riddle. "63 total games," he said, smiling at Kevin. "Next question."

Stung, Kevin looked at James. "How'd you do that?"

James was in his glory. "Easy. Single elimination. Everybody but the winner has to lose once." He smiled again.

Sometimes, especially in meetings, we ask questions for which we don't really need the answers. Like Kevin, we believe we need the answers, but we're mistaken. And sometimes we ask questions for reasons that are even less straightforward.

- One-upsmanship

- We're hoping to catch somebody "not knowing" or better yet, being wrong.

- Stalling

- Sometimes we ask questions

when we don't really need

the answers - We want to keep everyone occupied while we think things through, or until word on an important issue arrives by instant message.

- Hogging

- We realize that spending time on other issues leaves less time for the group to focus on us.

- Piling on

- We're hoping that the volume of questions about someone's task will create an impression that success is in doubt.

- Astuteness proof

- We believe that very few will understand the question we're asking, which will demonstrate yet again that we're so clever that we ought to be in charge of the galaxy. Or at least this team.

Even when the questioner's motives are pure, we can sometimes experience questions as attacks. When we do, we can become fearful or defensive, and the conversation can take a wrong turn.

There is a better way.

Instead of asking others for information, give information about your own internal state. If you're truly confused or ignorant about something, say so. Tell the group, "I don't understand that." Or, "It seems to me that X conflicts with Y."

If the group can clarify things for you, they will. If not, most will turn to the person who's responsible for the item, and then it will be clear that your muddle isn't just your own muddle.

When we replace questions with statements of personal ignorance or confusion, there are many fewer questions, many fewer statements of ignorance, and meetings go faster. Seems obvious to me. Or maybe I just don't understand why we ask each other so many questions. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Do you spend your days scurrying from meeting to meeting? Do you ever wonder if all these meetings are really necessary? (They aren't) Or whether there isn't some better way to get this work done? (There is) Read 101 Tips for Effective Meetings to learn how to make meetings much more productive and less stressful — and a lot more rare. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Effective Communication at Work:

Dismissive Gestures: III

Dismissive Gestures: III- Sometimes we use dismissive gestures to express disdain, to assert superior status, to exact revenge

or as tools of destructive conflict. And sometimes we use them by accident. They hurt personally, and

they harm the effectiveness of the organization. Here's Part III of a little catalog of dismissive gestures.

What We Don't Know About Each Other

What We Don't Know About Each Other- We know a lot about our co-workers, but we don't know everything. And since we don't know what we don't

know, we sometimes forget that we don't know it. And then the trouble begins.

Interrupting Others in Meetings Safely: I

Interrupting Others in Meetings Safely: I- In meetings we sometimes feel the need to interrupt others to offer a view or information, or to suggest

adjusting the process. But such interruptions carry risk of offense. How can we interrupt others safely?

Please Reassure Them

Please Reassure Them- When things go wildly wrong, someone is usually designated to investigate and assess the probability

of further trouble. That role can be risky. Here are three guidelines for protecting yourself if that

role falls to you.

Six Traps in Email or Text: I

Six Traps in Email or Text: I- Most of us invest significant effort in communicating by email or any of the various forms of text messaging.

Much of the effort is spent correcting confusions caused, in part, by a few traps. Knowing what those

traps are can save much trouble.

See also Effective Communication at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!