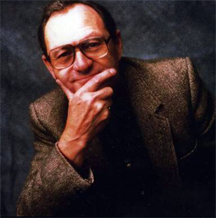

Robert Zajonc (1923 - 2008) was a Polish-born American social psychologist who is known for work on social and cognitive processes. He discovered and demonstrated experimentally the mere exposure effect. Because of this effect, repeated exposure to a given stimulus leads to a change of attitude about the stimulus. Photo credit ucsd.edu.

Some workplace discussions fail to converge because participants cannot agree that particular facts are indeed facts. This can happen even when the facts in question are objectively unquestionable: sales are increasing, or voluntary terminations spiked in Q2, or one of the technologies underlying some of our products is about to become obsolete. Debates about issues that aren't actually debatable are more harmful than merely wasting time. They can lead to the spread of misinformation on a scale that can prevent the organization from taking necessary steps that can avert organizational disaster.

In Part I of this exploration, we examined two barriers to accepting truth that are unfortunate, but which trace to cultural causes difficult to avoid. In this Part II, we sketch three additional barriers that trace to more individual frailties. And this leads to an important insight about persuasion in workplace debate.

We begin with sketches of three more barriers to accepting truth.

- Boredom

- For some people, in some life situations, energetic and passionate workplace debate provides welcome respite from intellectual boredom. They find irresistible the challenge of crafting arguments and chains of reasoning that are unexpected by their debate partners and which "win the day" for the side of the argument they're advocating.

- The intellectually bored generally aren't evil people. Their behavior usually returns to more acceptable patterns if we can find something for them to do that's both constructive and sufficiently challenging intellectually. A contributing cause of this problem, perhaps, is the failure of the supervisor of the bored person to first notice the boredom and then to take steps to address it effectively.

- Malevolence

- Malevolence is the desire to cause harm. In the context of workplace debate, malevolence can take many forms. Examples include taking steps to prevent debate from reaching closure; intentionally offending one or more debate participants; preventing a particular participant from attaining a goal; or causing all participants to be late for lunch.

- Straightforward Organizational power can bias our

judgment as we assess the

ideas or proposals of othersmotives for malevolence can include compulsion, revenge for perceived wrongs, or a desire to sabotage a rival's efforts. But more subtle motives can also occur. For example, the perpetrator might be acting at the behest of a person not participating in the debate, in exchange for a favor that person might deliver — or might already have delivered — in another context. - Power bias

- Organizational power can bias our judgment as we assess the ideas or proposals of others. People who possess organizational power can be reluctant to consider proposals that they believe might erode the power they do have; people who lack organizational power or who seek additional power can be reluctant to consider proposals that they believe might hinder their acquisition of power they don't have. So either way, power introduces a bias that can affect judgment and motivation.

- If power bias presents a significant barrier to people accepting truth, offering more truth or different truth is unlikely to bring the discussion to closure. In such situations, the pursuit or retention of power is the fundamental issue. Addressing that issue, or any issues that might be causing people to focus on their organizational power, is likely a more fruitful approach.

Certainly there are dozens more factors that lead us to be reluctant to accept truth. Fear is probably among the more important. Fear causes us to stay with what is, instead of what could be better. Virginia Satir expressed this idea by saying that people tend to prefer the familiar to the comfortable. The phenomenon that familiarity enhances preference, sometimes called the mere exposure effect, has since been demonstrated experimentally. [Fang 2007] Perhaps the most persuasive evidence for the existence of a mere exposure effect is the choice by advertisers to present identical advertisements repeatedly in multiple media.

Participants in workplace debates can also exploit the mere exposure effect, but to do so, they might need to adopt a long view. To expect that presenting unfamiliar facts for the first time can be persuasive in the moment might be expecting too much. The mere exposure effect suggests that presenting those same facts or similar facts repeatedly over the course of several debates might be more likely to achieve the intended result. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Effective Communication at Work:

Nasty Questions: I

Nasty Questions: I- Some of the questions we ask each other aren't intended to elicit information from the respondent. Rather,

they're poorly disguised attacks intended to harm the respondent politically, and advance the questioner's

political agenda. Here's part one a catalog of some favorite tactics.

Long-Loop Conversations: Asking Questions

Long-Loop Conversations: Asking Questions- In virtual or global teams, where remote collaboration is the rule, waiting for the answer to a simple

question can take a day or more. And when the response finally arrives, it's often just another question.

Here are some suggestions for framing questions that are clear enough to get answers quickly.

Four Overlooked Email Risks: II

Four Overlooked Email Risks: II- Email exchanges are notorious for exposing groups to battles that would never occur in face-to-face

conversation. But email has other limitations, less-often discussed, that make managing dialog very

difficult. Here's Part II of an exploration of some of those risks.

The Risks of Rehearsals

The Risks of Rehearsals- Rehearsing a conversation can be constructive. But when we're anxious about it, we can imagine how it

would unfold in ways that bias our perceptions. We risk deluding ourselves about possible outcomes,

and we might even experience stress unnecessarily.

Formulaic Utterances: III

Formulaic Utterances: III- Formulaic utterances are phrases that follow a pre-formed template. They're familiar, and they have

standard uses. "For example" is an example. In the workplace, some of them can help establish

or maintain dominance and credibility. Some do the opposite.

See also Effective Communication at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!