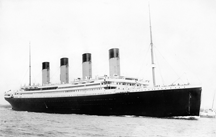

RMS Titanic departing Southampton on April 10, 1912. Widely acclaimed as "practically unsinkable," she sank in the early hours of April 15, on her first crossing of the Atlantic. Even the word practically couldn't sufficiently protect the prognosticators from risk. Photo by F.G.O. Stuart (1843-1923), courtesy Wikipedia.

You're working on a high-risk project, and the VP of Marketing wants you to reassure the product manager that you'll meet the promised delivery date. Or you've been tasked to find out why one of the company's products was recalled, and the CEO wants to know whether a repetition could ever happen. Or some other embarrassing event has occurred, and it has fallen to you to find a path forward. Isaac, who was in the lead of whatever unit got into such a mess (if the event is in the past), or who is in the lead of the unit that could create a future mess, has asked you to "please reassure them," that everything will be OK and all is well.

Isaac has given you his word that all will be well. That's nice, but very far from good enough. If you do as Isaac asks, your career is at risk.

Here are some guidelines for avoiding your own entanglement in the looming failure you've been charged with investigating.

- Understand your personal risks

- Although your role as investigator is legitimate on the surface, it's possible that your real task is to provide the answer almost everyone wants: everything will be OK. If there's strong evidence that everything will be OK, the risk to you is small. But unless you have access to independent, objective expertise, or unless you're qualified — and permitted and able — to assess the evidence yourself, you'll be relying on the judgments of others if you declare the situation under control. That could be a very risky act indeed.

- Nobody can predict the future

- Assurances Although your role as investigator

is legitimate on the surface, it's

possible that your real task is to

provide the answer almost everyone

wants: everything will be OKof the 100% kind about future events, from absolutely anyone, no matter how respected or expert, are so much bilge water. Nothing about the future is 100% predictable. There's always a small chance of the unexpected occurring. The Titanic was widely believed to be "practically unsinkable." - When you receive such 100% assurances, ask probing questions of the person providing the assurances. Start with, "How can you be 100% certain of anything involving the future?" And get their responses in writing. Such things look a whole lot dumber in print than they sound in person.

- Be judicious in your reporting

- If you can't persuade Isaac to be more circumspect, then gather enough information to provide a foundation for a report along the lines of, "They seem convinced that all will be well, but I couldn't find hard data strong enough to support their claims."

- You probably aren't free to refuse to pass Isaac's claims along, but you're certainly free to include your own assessment along with Isaac's claims. In formulating your own assessment, be careful to restrict it to facts. Unless you have justification, you really can't say that Isaac's claims are false. But you probably can say that you haven't found support for Isaac's claims.

When you do provide the result of your investigation, take care to be explicit if you're merely passing along the judgments of others. Express your projections in terms of probabilities, quantified to the extent possible. If you can supply percentages, do so, but otherwise use phrases like, "strong likelihood," or "small chance." For example, you could say that there's a 90% chance that things are OK.

If in your judgment a report about the uncertain future is required to make predictions without reference to probabilities or chance, there's an elevated likelihood that you've been cast in the role of someone to be blamed in case all does not go well. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Workplace Politics:

Managing Pressure: Communications and Expectations

Managing Pressure: Communications and Expectations- Pressed repeatedly for "status" reports, you might guess that they don't want status —

they want progress. Things can get so nutty that responding to the status requests gets in the way of

doing the job. How does this happen and what can you do about it? Here's Part I of a little catalog

of tactics and strategies for dealing with pressure.

No Tangles

No Tangles- When we must say "no" to people who have superior organizational power, the message sometimes

fails to get across. The trouble can be in the form of the message, the style of delivery, or elsewhere.

How does this happen?

Cyber Rumors in Organizations

Cyber Rumors in Organizations- Rumor management practices in organizations haven't kept up with rumor propagation technology. Rumors

that propagate by digital means — cyber rumors — have longer lifetimes, spread faster, are

more credible, and are better able to reinforce each other.

Self-Importance and Conversational Narcissism at Work: I

Self-Importance and Conversational Narcissism at Work: I- Conversational narcissism is a set of behaviors that participants use to focus the exchange on their

own self-interest rather than the shared objective. This post emphasizes the role of these behaviors

in advancing the participant's sense of self-importance.

Off-Putting and Conversational Narcissism at Work: II

Off-Putting and Conversational Narcissism at Work: II- Having off-putting interactions is one of four themes of conversational narcissism. Here are five behavioral

patterns that relate to off-putting interactions and how abusers employ them to distract conversation

participants from the matter at hand.

See also Workplace Politics for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!