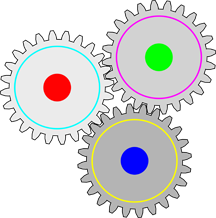

Three gears in a configuration that's inherently locked up. Any combination of an odd number of planar gears configured in a loop is inherently locked. Even though, at a local scale, the configuration looks like it might do something useful, when we examine it as a whole, we can see that it cannot do anything at all. So it is with collaborations in which participants harbor disjoint awareness of each other's activity and intentions. Image by J_Alves.

Many modern organizations achieve their objectives by organizing themselves into teams or other collaborative structures. And because their people are working as collaborators, they need some awareness of what their teammates are doing or what people in other collaborations are doing. But in forming or maintaining shared awareness of each other's work, people often encounter a problem I call disjoint awareness.

Disjoint awareness is a mismatch between what people believe their collaborators are doing or intending and what their collaborators are actually doing or intending. It can also denote a mismatch at the level of an entire team — a mismatch between what Team A believes Team B is doing and what Team B is actually doing. So disjoint awareness is due to a mismatch between the collaborators' awareness of each other's work and the awareness they would actually need if they were to avoid interfering with each other.

The mismatch can appear as a result of numerous phenomena, including ignorance, misconceptions, willful blindness, or unintended consequences of security measures. We'll examine some drivers of disjoint awareness in coming issues. To understand what we can do to reduce the incidence of disjoint awareness, let's begin by exploring its nature and effects.

A fictitious scenario

Here's an example of a scenario in which disjoint awareness reduces the chances of an organization achieving its objectives.

But the problem of disjoint awareness isn't restricted to the BAT or to administrative or executive teams. In this fictitious scenario, many of the people who sponsor or manage the numerous projects in IT did have risk plans to cover budget cutbacks, but those plans weren't always coordinated with each other. That is, very few projects had plans for coordinating with other projects to revise schedules or devise alternative approaches to mitigate the effects of the cuts collectively. Such plans would have required more complete awareness of the changing needs and changing status of other projects — awareness most of the project managers lacked at the time the cuts were announced.

As a means of Disjoint awareness denotes a

deficiency in people's awareness of

what their collaborators are doingensuring that the team and the organization achieve their objectives, some collaborators focus almost exclusively on achieving their own objectives. But as members of a team, it isn't enough to "do our part." We must go about doing our parts in ways that allow, enable, or support others as they do their parts. Just as important: as we do our part, we must avoid interfering with others as they do theirs.

The zeroth step required for avoiding interference with the work of our collaborators is awareness of how our own actions might interfere with teammates' work. It's difficult to avoid interfering with others unless we're somewhat aware of what they're doing or planning to do, and how our own activities might interfere with theirs. That's why a narrow focus on "doing my part" creates a risk of disjoint awareness, and consequent interference with the work of others.

And the problem transcends the individual. In complex organizations that have dozens or hundreds of teams, each team pursues its own objectives. And like the individual members of a single team, each team must have some continually refreshed awareness of the work of other teams. Absent that awareness, one team might interfere with others as all pursue their own objectives. That's what happened with Daffodil, Marigold, and the BAT.

Last words

So for any given objective and for any set of teams, there's an optimal set of awarenesses that corresponds to an acceptably low level of interference between teams. If the respective awarenesses of all involved don't match that optimal set, we have a state of disjoint awareness, and collaborators or even whole teams are prone to interfere with each other.

Next time we'll examine some of the phenomena that tend to produce disjoint awareness. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Occasionally we have the experience of belonging to a great team. Thrilling as it is, the experience is rare. In part, it's rare because we usually strive only for adequacy, not for greatness. We do this because we don't fully appreciate the returns on greatness. Not only does it feel good to be part of great team — it pays off. Check out my Great Teams Workshop to lead your team onto the path toward greatness. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness:

Dangerous Phrases

Dangerous Phrases- I recently upgraded my email program to a new version that "monitors messages for offensive text."

It hasn't worked out well. But the whole affair got me to think about everyday phrases that do tend

to set people off. Here's a little catalog.

When We Need a Little Help

When We Need a Little Help- Sometimes we get in over our heads — too much work, work we don't understand, or even complex

politics. We can ask for help, but we often forget that we can. Even when we remember, we sometimes

hold back. Why is asking for help, or remembering that we can ask, so difficult? How can we make it easier?

Selling Uphill: The Pitch

Selling Uphill: The Pitch- Whether you're a CEO or a project champion, you occasionally have to persuade decision makers who have

some kind of power over you. What do they look for? What are the key elements of an effective pitch?

What does it take to Persuade Power?

How to Make Meetings Worth Attending

How to Make Meetings Worth Attending- Many of us spend seemingly endless hours in meetings that seem dull, ineffective, or even counterproductive.

Here are some insights to keep in mind that might help make meetings more worthwhile — and maybe

even fun.

Remote Facilitation in Synchronous Contexts: I

Remote Facilitation in Synchronous Contexts: I- Whoever facilitates your distributed meetings — whether a dedicated facilitator or the meeting

chair — will discover quickly that remote facilitation presents special problems. Here's a little

catalog of those problems, and some suggestions for addressing them.

See also Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!