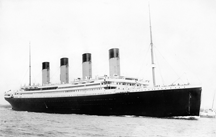

RMS Titanic departing Southampton on April 10, 1912. Widely acclaimed as "practically unsinkable," she sank in the early hours of April 15, on her first crossing of the Atlantic. Even the word practically couldn't sufficiently protect the prognosticators from risk. Photo by F.G.O. Stuart (1843-1923), courtesy Wikipedia.

A common pattern in problem solving and product development is known as proof of concept (POC). In a proof-of-concept exercise, we charter a team and give them access to what we believe to be a package of resources sufficient for building a demonstration of the concept we're trying to study. It seems like a reasonable approach. Proof of concept limits risk by limiting the scale of the trial. Then, so the theory goes, if the trial works we can scale up with a great degree of confidence. If the trial doesn't work, we make adjustments and try again. But for problems that require much scaling up proof-of-concept is an unsafe choice. The approach we really need is disproof of concept.

Bias in the proof-of-concept concept

The goal The name "proof of concept" is

actually part of the problem.

It communicates and reinforces

the bias of the investigation.of proof-of-concept exercises is to find a way to make the big idea work. That's why we call them proof-of-concept exercises. To achieve that goal, the team makes a string of decisions and assumptions designed to help it reach the goal. The problem with this approach is that it encourages a bias. That bias arises from three factors: the name of the POC approach, a conflict of interest, and the politics of POC teams.

- The name "proof of concept"

- The name "proof of concept" is actually part of the problem. The name communicates and reinforces the bias of the investigation. In essence, the team isn't investigating the properties of the concept or any preliminary implementation of the concept. Rather, the name communicates the fact that the team is responsible for proving the validity of the concept. Instead of searching for adjustments that strengthen the concept, the team focuses on finding ways — any ways at all — to demonstrate that the concept works.

- An inherent conflict of interest

- The conflict of interest arises from the conflict between the overall goal — make the idea work — and another goal, often unspoken: find the weaknesses, misconceptions, and shortcomings in the concept under study. Indeed, some of these POC teams take as their charter the necessity of proving that the concept works. For them, failure is not an option. For them, the concept must work because they believe that failure to prove the concept would raise questions about their personal capabilities and, in some cases, their loyalty to the organization.

- The politics of POC teams

- To be a member of a POC team is to recognize the politics of failure. The framing of the team's mission is to prove the concept. Team success is defined as proving the concept. Team failure is failing to prove the concept. One result of this framing of the team's mission is the tendency of some POC teams to search for the set of special cases and circumstances in which they can prove the concept. Finding those circumstances enables them to declare that they achieved the goal, subject to constraints. Example: A POC team studying the plans for the Titanic might have found that the Titanic was a fine, safe, ocean liner provided it doesn't run into icebergs — or anything else unexpected. The problem with this kind of conclusion is that it isn't a proof of concept; it's a proof of concept with some very important contingencies. But politically savvy POC teams find it difficult to choose any other course.

Disproof of concept

A significant risk of the POC approach is that the POC team might expend resources — and more important, calendar time — discovering conditions and devising adjustments that make the concept workable. In one unfortunate scenario, the POC team does find conditions and adjustments that make the concept workable, but the conditions and/or adjustments aren't acceptable in anticipated field conditions. That is, the concept works in the POC environment, but it isn't feasible at full scale. For teams that want to avoid producing this outcome too late in the investigation to be helpful, a very useful alternative is an approach based on disproof of concept (DOC).

In the disproof-of-concept approach, the DOC team aims to find the "fatal flaws" in the concept as quickly as possible. It's actually a variant of the "fail faster" approach to innovation. The DOC approach recognizes that calendar time is the most precious of all resources. By uncovering fatal flaws early, the DOC approach affords designers and strategists early warning of the need for adjustments. And with early warning they have greater freedom and a wider array of options for making adjustments. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Projects never go quite as planned. We expect that, but we don't expect disaster. How can we get better at spotting disaster when there's still time to prevent it? How to Spot a Troubled Project Before the Trouble Starts is filled with tips for executives, senior managers, managers of project managers, and sponsors of projects in project-oriented organizations. It helps readers learn the subtle cues that indicate that a project is at risk for wreckage in time to do something about it. It's an ebook, but it's about 15% larger than "Who Moved My Cheese?" Just . Order Now! .

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Problem Solving and Creativity:

Poverty of Choice by Choice

Poverty of Choice by Choice- Sometimes our own desire not to have choices prevents us from finding creative solutions. Life

can be simpler (if less rich) when we have no choices to make. Why do we accept the same tired solutions,

and how can we tell when we're doing it?

We Are All People

We Are All People- When a team works to solve a problem, it is the people of that team who do the work. Remembering that

we're all people — and all different people — is an important key to success.

Workplace Barn Raisings

Workplace Barn Raisings- Until about 75 years ago, barn raising was a common custom in the rural United States. People came together

from all parts of the community to help construct one family's barn. Although the custom has largely

disappeared in rural communities, we can still benefit from the barn raising approach in problem-solving

organizations.

Guidelines for Curmudgeon Teams

Guidelines for Curmudgeon Teams- The curmudgeon team is a subgroup of a larger team. Their job is to strengthen the team's conclusions

and results by raising thorny issues that cause the team to reconsider the path it's about to take.

In this way they help the team avoid dead ends and disasters.

Thirty Useful Questions

Thirty Useful Questions- Whether solving technical problems, creating plans, or puzzling through political tangles, asking the

right questions can be the key to finding useful approaches. An example: What questions would I like

to know the answers to?

See also Problem Solving and Creativity for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!