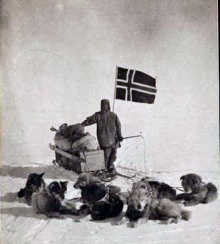

Oscar Wisting, a member of Roald Amundsen's expedition to reach the South Pole, and his dog team in triumph at the South Pole in 1911. In the world of European polar exploration, hauling equipment in dog sleds was controversial at the time, even though Arctic peoples had been working with dogs in this way for millennia.

Although most readers of this post no doubt regard dogs as pets and companions, Amundsen and his party viewed their dogs differently. In some sense, they viewed their dogs as friends and collaborators, as willing partners in the effort to reach the South Pole. That the humans killed many of the canines when the task demanded it (as planned) doesn't contradict this view, for the slaughter of the dogs was extremely upsetting to the explorers. But such was the ethos of the day, and the imperatives of the situation. As Amundsen later wrote about the mood of the explorers after the deed was done, "The holiday humour that ought to have prevailed in the tent that evening — our first on the plateau — did not make its appearance; there was depression and sadness in the air — we had grown so fond of our dogs."

The photo is from Amundsen's account of his journey to the South Pole, The South Pole, (now available from Cooper Square Press, but originally published in 1913 by J. Murray). It also appears in Amundsen's autobiographical work, My Life as an Explorer (Doubleday, Page &

Company, New York: 1927). The photo is part of the collection of the National Library of Australia.

We often use the words collaboration and cooperation as if they were interchangeable. They are not. They're similar, in that they both denote processes in which multiple people (or entities) work in such a way that their respective efforts are closely related. And from a distance, people who are cooperating and people who are collaborating can seem to be engaged in the same way. But they are not.

To see that the two terms — collaboration and cooperation — have different meanings, we need only reflect on how we use language. For example, within a business unit working on multiple projects, when we mean to refer to a group of people who are collaborating with each other, we can speak of "a collaboration." But when we mean to refer to a group of people who are cooperating with each other, we rarely speak of "a cooperation." Indeed, Microsoft Word, which I'm using to compose this post, indicates a possible grammatical error at every point at which I use the word cooperation in that way.

We do have the noun "cooperative," which means, "an enterprise or organization owned by and operated for the benefit of those using its services." [Mish 2005] But the noun "cooperative" doesn't apply to a group of people who are cooperating with each other within a business unit.

Because we so rarely use the word cooperation as a noun to refer to a workplace group of cooperating people, I feel free to use it in that sense in this post (and the next two) without risking ambiguity. So in this post, when I refer to "a cooperation" I mean a group of people who are cooperating to achieve their various respective goals.

When When we mean to refer to a group of

people who are cooperating with each

other, we rarely speak of "a cooperation"we assess the performance of people in an organization, we must take care to distinguish cooperation from collaboration. And when we divide the work of a business unit, we must choose carefully between asking people to collaborate and asking those same people to cooperate. When we confuse cooperation and collaboration, we can get disappointing results because those results might differ from what we expect. In the next post I suggest some reasons why such disappointment isn't surprising. To support that exploration, I begin by examining more closely the differences between collaborations and cooperations.

- Objective

- A collaboration forms when individuals or entities form an alliance to achieve a single shared objective. [Huggett 2018] The members of the collaboration all consider themselves to be co-authors of the work product the collaboration produces.

- A cooperation is a loose collection of individuals or entities who are willing to assist each other in achieving their respective individual objectives, or the objectives of others. The assistance they provide might include actual effort, or it might consist of merely adjusting their schedules or shifting responsibilities to accommodate each other.

- Identity

- Collaborations have defined identities. They have names. They might be categorized as projects, initiatives, skunk works, or strategic partnerships. Some even have their own facilities and financial resources.

- Cooperations rarely have names. They are rarely categorized differently from the organizational units that host them. For example, although the people of the Marketing Department cooperate with Engineering in presenting Product X to the market, they do so as a consequence of their functional responsibility, rather than as a consequence of belonging to a cooperation with a defined identity.

- Origins

- Collaborations usually form by intention. They often happen when people recognize a need and acknowledge that they cannot meet that need acting alone. The prospective collaborators know what the missing pieces are, and they seek others who can provide those pieces. When they find willing partners, the collaboration is formed. Custom within the collaboration resolves any resource usage conflicts.

- Cooperations don't form by intention, and we rarely recognize them as entities. The people of a cooperation just go about their business without actively obstructing each other. When there is a conflict about the use of some resource, the affected parties negotiate shared use. When one member of the cooperation needs something from another, they negotiate a resolution. When cooperation breaks down, and negotiations fail to resolve resource usage conflicts, organizational hierarchy prevails. When one member achieves his/her/its objective, that member might adopt a new objective, or withdraw from the cooperation, or move on, while the other members of the cooperation press on toward their objectives. If there is a shared recognition of success, the credit goes to the hosting organization, rather than to the cooperation.

- Lifecycle

- Collaborations have inception dates and termination dates. They usually persist continuously between those dates, but some collaborations experience suspension and resumption. Terminations usually coincide with achieving their objectives, which might be delivery of a working system, successfully executing some action, or issuing a final report. Early terminations are possible. In some cases, collaborations can be reorganized into new or existing collaborations.

- Because cooperations lack identities, they also lack inception dates and termination dates. Many persist indefinitely, though they might vary dramatically in their effectiveness over their lifetimes.

- A vision that transcends operations

- A collaboration is an alliance of individuals or entities working to achieve a single shared objective. For example, the carpenters, electricians, and plumbers working on constructing a house form a collaboration. They share a coherent vision — they understand that they're building a house. They must cooperate to do this. But because the unexpected is inevitable in such activities, from time to time they must collaborate to modify the vision to make it achievable.

- For cooperations to be effective, their members must share an understanding of what effectiveness is. They must agree to adjust their activities from time to time to enable the cooperation to operate smoothly. For example, the staff of your local public library performs various tasks as required by their customers. They all agree on an operational vision: they provide service that meets certain performance goals to serve the community. They provide that service by cooperating with each other. But the cooperation itself requires no more elaborate vision regarding its objectives.

Last words

The differences between collaborations and cooperations manifest themselves in a range of indirect effects. For example, many performance management systems include standards that encourage cooperative behavior. They also include standards intended to encourage high performance within the collaborations people are assigned to. At times, efforts to meet one standard conflict with efforts to meet another. That is, within a collaboration, it's possible to place your own performance at risk by extending yourself to cooperate with members of another collaboration. This tension, coupled with pressure for high individual performance, can cause people to place cooperation at lower — or lowest — priority.

In Part II of this exploration I examine the risks associated with confusing collaboration with cooperation. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Occasionally we have the experience of belonging to a great team. Thrilling as it is, the experience is rare. In part, it's rare because we usually strive only for adequacy, not for greatness. We do this because we don't fully appreciate the returns on greatness. Not only does it feel good to be part of great team — it pays off. Check out my Great Teams Workshop to lead your team onto the path toward greatness. More info

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness:

Team-Building Travails

Team-Building Travails- Team-building is one of the most common forms of team "training." If only it were the most

effective, we'd be in a lot better shape than we are. How can we get more out of the effort we spend

building teams?

Our Last Meeting Together

Our Last Meeting Together- You can find lots of tips for making meetings more effective — many at my own Web site. Most are

directed toward the chair, or the facilitator if you have one. Here are some suggestions for everybody.

Wacky Words of Wisdom

Wacky Words of Wisdom- Words of wisdom are so often helpful that many of them have solidified into easily remembered capsules.

We do tend to over-generalize them, though, and when we do, trouble follows. Here are a few of the more

dangerous ones.

How to Get Out of Firefighting Mode: I

How to Get Out of Firefighting Mode: I- When new problems pop up one after the other, we describe our response as "firefighting."

We move from fire to fire, putting out flames. How can we end the madness?

Defect Streams and Their Sources

Defect Streams and Their Sources- Regarding defects as elements of a stream provides a perspective that aids in identifying causes other

than negligence. Examples of root causes are unfunded mandates, misallocation of the cost of procedure

competence, and frequent changes in procedures.

See also Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!