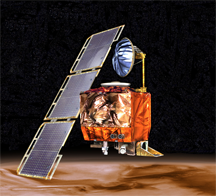

NASA's Mars Climate Orbiter, which was lost on attempted entry into Mars orbit on Sptember 23, 1999. It either crashed onto the surface of Mars or escaped Mars gravity and entered a solar orbit. The failure was due to mismatch of measurement units in two software systems. A NASA-built system used metric units and a system built by Lockheed Martin used "English" units. In the terminology of this post, the NASA team and the Lockheed Martin team were using incompatible frames.

Some miscommunications can have dire consequences.

NASA artist's rendering courtesy Wikimedia.

In Part I of this exploration, I described three communication antipatterns that can arise independent of what we intend to communicate. In Part II I described antipatterns that arise, in part, because of the attributes of what we're communicating. In this last Part III, I focus on three kinds of confusions that arise from contextual factors.

As in the previous posts in this series, I use the name Eugene (E for Expressing) when I'm referring to the person expressing an idea, asking a question, or in some other way contributing new material to an exchange. And I use the name Rachel (R for Receiving) when I'm referring to the person Receiving Eugene's communication.

With that prolog, here are three antipatterns that increase the risk of miscommunication.

- Poor framing

- The frame of a message includes the specific context required to understand it. The specific context is the top layer of the knowledge stack. It includes specific vocabulary, acronyms, historic references, and the settings in which components must operate. Because framing terminology that also serves other purposes can create ambiguity, the frame includes information needed to resolve those ambiguities.

- Rachel (a recipient) If time constraints are tight,

the urge to find communications

shortcuts can be overwhelmingcan understand only well-framed messages. A poorly framed message almost certainly leads to miscommunication. - Examples are among the most powerful tools for mitigating the risk of poor framing. If Eugene (the person Expressing the message content) doesn't include examples, Rachel would do well to ask for them, or perhaps to formulate one herself and ask Eugene to confirm that it's a relevant example.

- Similarity to previous problems

- If time constraints are tight, the urge to find communications shortcuts can be overwhelming. One very appealing shortcut involves viewing the current problem as another instance of a previously solved problem. That approach can work well at times, because it saves some of the effort associated with defining the problem and then finding a solution.

- But in our haste we sometimes overlook important distinctions between the current problem and the problem previously solved. For example, when Eugene has taken this shortcut, and Rachel or others haven't, the opportunities for miscommunication are numerous. Worse, recognizing the miscommunications can be difficult when the parties are talking about different problems using similar vocabularies.

- At some point when this has occurred, someone might say, "Wait, are we talking about the same thing?" If you feel the urge to ask such a question, you could be caught in this kind of trap.

- Closely held information

- If one of the parties to the exchange, let's say Eugene, has access to closely held information, special kinds of miscommunications can occur. Suppose that Eugene knows about Secret 1, but Rachel doesn't. And suppose that Secret 1 is relevant to their exchange. We can easily imagine scenarios in which Eugene — knowingly or unknowingly — allows Rachel to exit the conversation with a significant misconception. But there's nothing special about these roles — we can swap roles and the problem could still arise.

- Eugene's failure (or choice) to inform Rachel that she is misinterpreting some part of their exchange might not reflect badly on Eugene. For example, he might be constrained by law or by role not to reveal anything about Secret 1, including its very existence.

- Both Eugene and Rachel might simultaneously possess closely held information that they cannot reveal to the other. Navigating in environments in which these scenarios are common can be challenging.

Last words

These three posts have explored miscommunications that arise in three categories: causes independent of content, causes that depend on content, and causes that depend on contextual factors. Other frameworks are possible, of course. To search for causes of miscommunication in your context, begin by collecting examples. If you can devise a framework that covers a significant share of your examples, you can use that framework to anticipate other communication antipatterns. Anticipation is among the first steps toward prevention. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are you fed up with tense, explosive meetings? Are you or a colleague the target of a bully? Destructive conflict can ruin organizations. But if we believe that all conflict is destructive, and that we can somehow eliminate conflict, or that conflict is an enemy of productivity, then we're in conflict with Conflict itself. Read 101 Tips for Managing Conflict to learn how to make peace with conflict and make it an organizational asset. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Effective Communication at Work:

Some Truths About Lies: I

Some Truths About Lies: I- However ethical you might be, you can't control the ethics of others. Can you tell when someone knowingly

tries to mislead you? Here's Part I of a catalog of techniques misleaders use.

Interviewing the Willing: Tactics

Interviewing the Willing: Tactics- When we need information from each other, even when the source is willing, we sometimes fail to expose

critical facts. Here are some tactics for eliciting information from the willing.

Dismissive Gestures: II

Dismissive Gestures: II- In the modern organization, since direct verbal insults are considered "over the line," we've

developed a variety of alternatives, including a class I call "dismissive gestures." They

hurt personally, and they harm the effectiveness of the organization. Here's Part II of a little catalog

of dismissive gestures.

Inbox Bloat Recovery

Inbox Bloat Recovery- If you have more than ten days of messages in your inbox, you probably consider it to be bloated. If

it's been bloated for a while, you probably want to clear it, but you've tried many times, and you can't.

Here are some effective suggestions.

Reframing Revision Resentment: II

Reframing Revision Resentment: II- When we're required to revise something previously produced — prose, designs, software, whatever,

we sometimes experience frustration with those requiring the revisions. Here are some alternative perspectives

that can be helpful.

See also Effective Communication at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!