Many believe that "You get what you measure." The belief persists, in part, because of anecdotal evidence; because some experiments do appear to be consistent with the assertion; and because so many of us believe that the rest of us believe it.

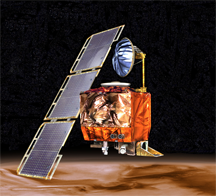

The Mars Climate Orbiter, as it would have appeared if it had not been lost upon entry into Mars orbit. Mars Climate Orbiter was lost because of a mismatch between Metric and English units in a file used by its trajectory models. The measurements were all objective, and they were even precise, but confusion led to a loss of the orbiter. Photo courtesy U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Still, there are reasons to question its validity. What follows is a catalog of possible explanations for variances between the promise and the reality of metrics-based management. In this Part I, we examine three assumptions underlying the measurement process. See Part II and Part III for more.

- We assume that indirect measurements work

- Sometimes we try to measure attributes that aren't directly measurable. For instance, when we try to measure immeasurables like loyalty or initiative, we actually measure something else that we assume is highly correlated with what we're trying to measure. We usually do this using interviews or surveys.

- But too often, rigorous proof of the assumed correlation is unavailable. Sometimes, we comfort ourselves, saying, "it's so obvious," but this is risky — the history of management, psychology, and science is replete with assumptions that, though obvious, were nonetheless false.

- We assume that all attributes are measurable

- The word "measurement" evokes our experiences determining physical attributes like length, weight, or temperature. This leads us to assume that whatever we want to know can be determined by a suitable measurement, but that assumption can lead to trouble. Consider something as important as progress. Suppose a team has been working for three weeks, when, suddenly, someone realizes that their entire approach will never work. This is certainly progress — they've learned something important. But it probably won't register as progress in the organization's metrics. Most likely, it will be reported as a setback.

- Measuring nonphysical We assume (wrongly)

that all organizational

attributes are measurableattributes, such as the advance of knowledge, is often possible when changes are incremental. But at times, our metrics fail, and they tend to fail precisely when we most want to know where we stand. - We assume that objectivity implies precision

- Sometimes we use measures that are objective but imprecise. That is, we assume wrongly that multiple identical measurements would yield nearly identical results. For instance, when we measure attitudes using a survey "instrument," we assume that the results we obtain are relatively context-independent. We don't actually know that the results are independent of, say, the time of the month, or the price of the company's shares — we just assume it.

- Rarely do we test these assumptions. Indeed, we often assume that these factors do affect the results. We know this because we sometimes observe organizations gaming the measurement for favorable results, or trying to influence the results by releasing favorable news.

Assumptions like these can account for some — not all — of the poor performance of metrics-based management. In a future issue, we'll examine the effects of employee behavior. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness:

Tactics for Asking for Volunteers: I

Tactics for Asking for Volunteers: I- CEOs, board chairs, department heads and team leads of all kinds sometimes seek people to handle specific,

time-limited tasks. Asking the group for volunteers works fine — usually. There are alternatives.

A Review of Performance Reviews: The Checkoff

A Review of Performance Reviews: The Checkoff- As practiced in most organizations, performance reviews, especially annual performance reviews, are

toxic both to the organization and its people. A commonly used tool, the checkoff, is especially deceptive.

How to Get Out of Firefighting Mode: I

How to Get Out of Firefighting Mode: I- When new problems pop up one after the other, we describe our response as "firefighting."

We move from fire to fire, putting out flames. How can we end the madness?

Listening to Ramblers

Listening to Ramblers- Ramblers are people who can't get to the point. They ramble, they get lost in detail, and listeners

can't follow their logic, if there is any. How can you deal with ramblers while maintaining civility

and decorum?

Risk Creep: I

Risk Creep: I- Risk creep is a term that describes the insidious and unrecognized increase in risk that occurs despite

our every effort to mitigate risk or avoid it altogether. What are the dominant sources of risk creep?

See also Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!