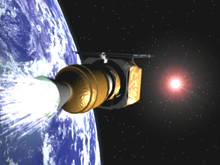

Computer-generated image of the third stage ignition, sending the Mars Climate Orbiter (MCO) to Mars in December, 1998. The spacecraft eventually broke up in the Martian atmosphere as a result of what is now often called the "metric mix-up." The team at Lockheed Martin that constructed the spacecraft and wrote its software used Imperial units for computing thrust data. But the team at JPL that was responsible for flying the spacecraft was using metric units. The mix-up was discovered after the loss of the spacecraft by the investigation panel established by NASA.

One of the many operational changes deployed as a result of this loss was increased use of reviews and inspections. While we do not know why reviews and inspections weren't as thorough before the loss of the MCO as they are now, one possibility is the effects of confirmation bias in assessing the need for reviews and inspections. Image courtesy Engineering Multimedia, Inc., and U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

As we've seen, confirmation bias causes us to seek confirmation of our preconceptions, while we avoid contradictions to them, always outside our awareness. [Nickerson 1998] last time, we explored the effects of confirmation bias on thought processes. Let's now explore its affects on management processes. Here are four ways people use confirmation bias to reinforce their preconceptions about managing.

- The Pygmalion Effect

- In the Pygmalion Effect [Livingston 1991], managers' expectations influence how they see employee performance, which influences employees' performance itself. This transcends confirmation bias, which applies only to the owner of the preconceptions.

- But employee performance is rarely deficient in every way. Although it might be substandard, it almost certainly has some bright spots. But managers with negative preconceptions tend to undervalue those bright spots, and overvalue problematic performance factors. Thus, confirmation bias provides a foundation for the Pygmalion Effect by hardening the manager's preconceptions. In extreme cases, it might even be the precipitating cause of the entire incident.

- Lock-in

- Lock-in is a pattern of dysfunction that appears in decision making when an individual or group escalates its commitment to a low-quality prior decision, often in spite of the availability of superior alternatives. Lock-in can be a symptom of confirmation bias, because it helps the decision maker resist information or ideas that call preconceptions into question.

- To some extent, educating decision makers about the role of confirmation bias in lock-in can help control lock-in. But this tactic is relatively ineffective once lock-in happens, because the educator can appear to be furthering an agenda of opposition to the prior decision.

- The backfire effect

- When we correct misstatements made by others, their beliefs in their misstatements sometimes intensify. The attempt to correct backfires.

- When this happens, it's often caused by confirmation bias, as the people corrected try to preserve their preconceptions.

- Aversion or resistance to reviews, inspections, and dry runs

- Structured defect discovery activities are intended to improve the quality of work products by uncovering defects. The experience of having one's work inspected can therefore be painful to those who want to believe that their work is flawless, or if not flawless, better than it actually is. That's why resistance to structured defect discovery activities is often little more than a manifestation of the dynamics of confirmation bias.

- The most straightforward At times, confirmation bias tends

to reinforce our preconceptions

about managing and about the

people we manageform of resistance is direct opposition. People might complain about the activity's effectiveness, or about the burden it places on busy people, or about the return on investment. But there are more subtle forms of resistance, too. For instance, some might withhold discovery of defects in one team's work product to return an earlier favor from others, or to incur a debt to be repaid later. Like lock-in, training in confirmation bias and its effects provides perhaps the best chance of controlling aversion to structured defect discovery activities.

If you doubt that confirmation bias affects your own management processes, examine your doubts for signs of confirmation bias. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

For more on the Pygmalion effect, see "Pygmalion Side Effects: Bowling a Strike," Point Lookout for November 21, 2001. For more about the lock-in, see "Indicators of Lock-In: I," Point Lookout for March 23, 2011.

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Emotions at Work:

Email Happens

Email Happens- Email is a wonderful medium for some communications, and extremely dangerous for others. What are its

limitations? How can we use email safely?

When Naming Hurts

When Naming Hurts- One of our great strengths as Humans is our ability to name things. Naming empowers us by helping us

think about and communicate complex ideas. But naming has a dark side, too. We use naming to oversimplify,

to denigrate, to disempower, and even to dehumanize. When we abuse this tool, we hurt our companies,

our colleagues, and ourselves.

The Injured Teammate: I

The Injured Teammate: I- You're a team lead, and one of the team members is very ill or has been severely injured. How do you

handle it? How do you break the news? What does the team need? What do you need?

Good Change, Bad Change: II

Good Change, Bad Change: II- When we distinguish good change from bad, we often get it wrong: we favor things that would harm us,

and shun things that would help. When we do get it wrong, we're sometimes misled by social factors.

When Somebody Throws a Nutty

When Somebody Throws a Nutty- To "throw a nutty" — at work, that is — can include anything from extreme verbal

over-reaction to violent physical abuse of others. When someone exhibits behavior at the milder end

of this spectrum, what responses are appropriate?

See also Emotions at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!