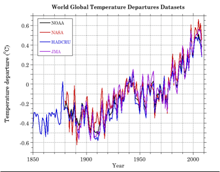

World global temperature departures from the 1951-1980 mean. The plot shows four data sets, including NASA, NOAA, the Climate Research Unit (CRU) of the University of East Anglia, and the Japan Meteorological Agency. All are very similar, and although there are significant overlaps between the respective data sources of these four agencies, each is applying its own analytical methods to that data. The CRU is the focus of what is often called "Climategate" — an allegation that climate researchers there (and presumably elsewhere) have used their scientific skill to conspire to produce a conclusion that matches their preconceptions, abusing their positions and violating their scientific integrity. The advocates of the Climategate position allege, among other things, that confirmation bias is at work in the scientific community and that global warming, if it exists at all, is not due to human activity. Scientists, including recently a scientist who had joined with the global warming deniers, have repeatedly debunked these allegations.

Interestingly, it is the advocates of Climategate who may provide the clearest examples of confirmation bias. One example of a justification of this assertion relates to what is here called "Hear no evil, see no evil." Let us concede that, across any given field of scientific research, scientific integrity is rarely upheld perfectly and that in any area of scientific research, there are instances of scientific fraud. Two critical questions then become: "What is the incidence of scientific fraud, by field of research?" and "What is the expected incidence of scientific fraud in climatology?" Finding a single instance of scientific fraud does not in itself invalidate all research in a given field, nor does it invalidate the research done by others in that field, nor does it prove that the research performed in that field is any less credible than is the research performed in other fields. Any conclusion as to the credibility of climatological research must rest on some estimate of the integrity of the field itself relative to others. But Climategate advocates have done no such studies of which I am aware, or, at least, they have not publicized this element of the argument. For them it appears to be sufficient to call into question one group's work without establishing any kind of context for their subsequent conclusions. This could be explained as an unwillingness to test their conclusions, which is a hallmark of confirmation bias. Illustration courtesy The New Republic.

There is a cognitive bias known as confirmation bias that causes us to seek confirmation of our preconceptions, while we avoid information that might contradict them. [Nickerson 1998] It can also cause us to tend to overvalue information supporting our preconceptions, and undervalue information in conflict with them.

Last time, we explored indicators that confirmation bias might be taking place. Let's now explore how confirmation bias affects our thinking. Here are five ways people use confirmation bias — often outside their awareness — to reinforce their preconceptions.

- Hear no evil, see no evil

- We use many techniques for avoiding information that conflicts with preconceptions. In meetings, we deprive people of the floor if we regard their positions as threats to our preconceptions, or we're inattentive when they speak, or we place their agenda items last, hoping to run out of time. We ignore what they write and we distract others from paying attention to their contributions. For conferences, we use peer review to exclude them from programs altogether; we assign them to small, undesirable, or out-of-the-way venues; we schedule them for undesirable time slots; or we schedule them opposite events that we expect to be heavily attended.

- Consider carefully the spectrum of information sources to which you do pay attention. When others make choices for you (as happens in conferences), think about what has been excluded from the program.

- False memories

- Most research about false memories relates to the recovered memory techniques in common use a decade ago. In the workplace, false memories also play a role. When we recollect what someone said or wrote, we're risking confirmation bias.

- Take extra care when retrieving memories that support positions you hold — memory tends to provide data that supports what we believe, and it tends not to provide data that conflicts with what we believe.

- False reasoning

- When reasoning is subtle, we sometimes make mistakes. But when reasoning isn't especially challenging, we can still make errors, especially when we hurry or we're under stress.

- Because of confirmation bias, these errors tend to favor our preconceptions. Examine carefully any reasoned argument that supports preconceptions.

- False accusations

- Accusations that survive being subjected to testing against evidence are more likely to be valid. By limiting such testing, confirmation bias tends to increase the likelihood that accusations are false.

- Accusations need not be verbalized. Even when they're merely thoughts, they affect how we interact with the accused. Such accusations are especially prone to confirmation bias, because they are rarely subject to confrontation with evidence.

- Tiptoeing around the elephants

- The "elephant in the room" The "elephant in the room"

often takes the form of

information that contradicts

our preconceptionsoften takes the form of information that contradicts what we hope to be true — information that contradicts our preconceptions. Confirmation bias helps us defend against these contradictions. - When you sense the presence of an elephant in the room, check for contradictions of the group's hopes, dreams, and preconceptions.

Next time we'll examine the effects of confirmation bias on management processes. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

For more about "the elephant in the room," see "Stalking the Elephant in the Room: I," Point Lookout for June 9, 2010. For more about false accusations, see "Political Framing: Strategies," Point Lookout for May 6, 2009.

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Emotions at Work:

You Remind Me of Helen Hunt

You Remind Me of Helen Hunt- At a dinner party I attended recently, Kris said to Suzanne, "You remind me of Helen Hunt."

I looked at Suzanne, and sure enough, she did look like Helen Hunt. Later, I noticed that I

was seeing Suzanne a little differently. These are the effects of hat hanging. At work, it can damage

careers and even businesses.

A Guide for the Humor-Impaired

A Guide for the Humor-Impaired- Humor can lift our spirits and defuse tense situations. If you're already skilled in humor, and you

want advice from an expert, I can't help you. But if you're humor-impaired and you just want to know

the basics, I probably can't help you either. Or maybe I can...

Human Limitations and Meeting Agendas

Human Limitations and Meeting Agendas- Recent research has discovered a class of human limitations that constrain our ability to exert self-control

and to make wise decisions. Accounting for these effects when we construct agendas can make meetings

more productive and save us from ourselves.

Patterns of Conflict Escalation: I

Patterns of Conflict Escalation: I- Toxic workplace conflicts often begin as simple disagreements. Many then evolve into intensely toxic

conflict following recognizable patterns.

Heart with Mind

Heart with Mind- We say people have "heart" when they continue to pursue a goal despite obstacles that would

discourage almost everyone. We say that people are stubborn when they continue to pursue a goal that

we regard as unachievable. What are our choices when achieving the goal is difficult?

See also Emotions at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!