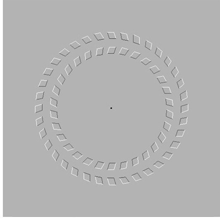

A visual illusion. While staring at the dot in the center of the image, move your head forward and back. You'll see the two rings of quadrilaterals rotate in opposite directions. They don't actually rotate at all, much less in opposite directions, but your visual system tells you that they do. Even after you're aware that this is an illusion, you can't make the illusion "go away." That is also the hallmark of cognitive biases. Even when we're aware of their effects, we can't manage to exercise unbiased judgments. To avoid the effects of a cognitive bias that affects personal judgment in a given situation, we must recruit the assistance of someone (or several someones) who aren't in that situation, and who thus aren't subject to that cognitive bias. Of course, because they could be subject to some other cognitive bias or biases, designing bias-avoidance procedures can be tricky. Image courtesy U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Google "scope creep" and you get over 10.1 million hits. Mission creep gets 15.6 million. Feature creep also gets over 20.2 million. That's pretty good for a technical concept, even if it isn't quite "miley" territory (222 million). The concept is known widely enough that anyone with project involvement has probably had first-hand experience with scope creep.

If we know so much about scope creep, why haven't we eliminated it? One simple possible answer: Whatever techniques we're using probably aren't working. Maybe the explanation is that we're psychologically challenged — that is, we, as humans, have a limited ability to detect scope creep, or to acknowledge that it's happening. If that's the case, a reasonable place to search for mechanisms to explain its prevalence is the growing body of knowledge about cognitive biases.

A cognitive bias is the tendency to make systematic errors of judgment based on thought-related factors rather than evidence. For example, a bias known as self-serving bias causes us to tend to attribute our successes to our own capabilities, and our failures to situational disorder.

Cognitive biases offer an enticing possible explanation for the prevalence of scope creep despite our awareness of it, because "erroneous intuitions resemble visual illusions in an important respect: the error remains compelling even when one is fully aware of its nature." [Kahneman & Tversky 1977] [Kahneman & Tversky 1979] Let's consider one example of how a cognitive bias can make scope creep more likely.

In their 1977 report, Kahneman and Tversky identify one particular cognitive bias, the planning fallacy, which afflicts planners. They The planning fallacy can lead to

scope creep because underestimates

of cost and schedule can lead

decision makers to feel that

they have time and resources

that don't actually existdiscuss two types of information used by planners. Singular information is specific to the case at hand; distributional information is drawn from similar past efforts. The planning fallacy is the tendency of planners to pay too little attention to distributional evidence and too much to singular evidence, even when the singular evidence is scanty or questionable. Failing to harvest lessons from the distributional evidence, which is inherently more diverse than singular evidence, the planners tend to underestimate cost and schedule.

But because the planning fallacy leads to underestimates of cost and schedule, it can also lead to scope creep. Underestimates can lead decision makers to feel that they have time and resources that don't actually exist: "If we can get the job done so easily, it won't hurt to append this piece or that."

Accuracy in cost and schedule estimates thus deters scope creep. We can enhance the accuracy of estimates by basing them not on singular data alone, but instead on historical data regarding organizational performance for efforts of similar kind and scale. And we can require planners who elect not to exploit distributional evidence in developing their estimates to explain why they made that choice.

In coming issues we'll examine other cognitive biases that can contribute to scope creep. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

More about scope creep

Some Causes of Scope Creep [September 4, 2002]

Some Causes of Scope Creep [September 4, 2002]- When we suddenly realize that our project's scope has expanded far beyond its initial boundaries — when we have that how-did-we-ever-get-here feeling — we're experiencing the downside of scope creep. Preventing scope creep starts with understanding how it happens.

Scopemonging: When Scope Creep Is Intentional [August 22, 2007]

Scopemonging: When Scope Creep Is Intentional [August 22, 2007]- Scope creep is the tendency of some projects to expand their goals. Usually, we think of scope creep as an unintended consequence of a series of well-intentioned choices. But sometimes, it's much more than that.

More Indicators of Scopemonging [August 29, 2007]

More Indicators of Scopemonging [August 29, 2007]- Scope creep — the tendency of some projects to expand their goals — is usually an unintended consequence of well-intentioned choices. But sometimes, it's part of a hidden agenda that some use to overcome budgetary and political obstacles.

The Perils of Political Praise [May 19, 2010]

The Perils of Political Praise [May 19, 2010]- Political Praise is any public statement, praising (most often) an individual, and including a characterization of the individual or the individual's deeds, and which spins or distorts in such a way that it advances the praiser's own political agenda, possibly at the expense of the one praised.

The Deck Chairs of the Titanic: Task Duration [June 22, 2011]

The Deck Chairs of the Titanic: Task Duration [June 22, 2011]- Much of what we call work is as futile and irrelevant as rearranging the deck chairs of the Titanic. We continue our exploration of futile and irrelevant work, this time emphasizing behaviors that extend task duration.

The Deck Chairs of the Titanic: Strategy [June 29, 2011]

The Deck Chairs of the Titanic: Strategy [June 29, 2011]- Much of what we call work is about as effective and relevant as rearranging the deck chairs of the Titanic. We continue our exploration of futile and irrelevant work, this time emphasizing behaviors related to strategy.

Ground Level Sources of Scope Creep [July 18, 2012]

Ground Level Sources of Scope Creep [July 18, 2012]- We usually think of scope creep as having been induced by managerial decisions. And most often, it probably is. But most project team members — and others as well — can contribute to the problem.

Scope Creep, Hot Hands, and the Illusion of Control [February 26, 2014]

Scope Creep, Hot Hands, and the Illusion of Control [February 26, 2014]- Despite our awareness of scope creep's dangerous effects on projects and other efforts, we seem unable to prevent it. Two cognitive biases — the "hot hand fallacy" and "the illusion of control" — might provide explanations.

Scope Creep and Confirmation Bias [March 12, 2014]

Scope Creep and Confirmation Bias [March 12, 2014]- As we've seen, some cognitive biases can contribute to the incidence of scope creep in projects and other efforts. Confirmation bias, which causes us to prefer evidence that bolsters our preconceptions, is one of these.

On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: I [April 23, 2025]

On Planning in Plan-Hostile Environments: I [April 23, 2025]- In most organizations, most of the time, the plans we make run into little obstacles. When that happens, we find workarounds. We adapt. We flex. We innovate. But there are times when whatever fix we try, in whatever way we replan, we just can't make it work. We're working in a plan-hostile environment.

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

The Risky Role of Hands-On Project Manager

The Risky Role of Hands-On Project Manager- The hands-on project manager manages the project and performs some of the work, too. There are lots

of excellent hands-on project managers, but the job is inherently risky, and it's loaded with potential

conflicts of interest.

The Politics of the Critical Path: I

The Politics of the Critical Path: I- The Critical Path of a project or activity is the sequence of dependent tasks that determine the earliest

completion date of the effort. If you're responsible for one of these tasks, you live in a unique political

environment.

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II- Plans are well known for working out differently from what we intended. Sometimes, the unintended outcome

is due to external factors over which the planning team has little control. Two examples are priming

effects and widely held but inapplicable beliefs.

Should We Do This?

Should We Do This?- Answering the question, "Should we do this?" is among the more difficult decisions organizational

leaders must make. Weinberger's Six Tests provide a framework for making these decisions. Careful application

of the framework can prevent disasters.

The Risk Planning Fallacy

The Risk Planning Fallacy- The planning fallacy is a cognitive bias that causes underestimates of cost, time required, and risks

for projects. Analogously, I propose a risk planning fallacy that causes underestimates of probabilities

and impacts of risk events.

See also Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!