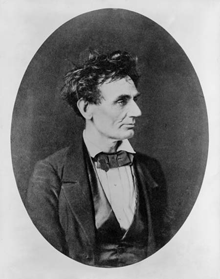

Abraham Lincoln as a young man about to become a candidate for U.S. Senate. It was in the context of this election campaign that the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates, between Lincoln and the incumbent Senator Stephen Douglas, took place. In these debates, Douglas took a generally pro-slavery position. Lincoln's position was not that of an abolitionist — he advocated for halting the extension of slavery to new territories.

During the debates, Douglas repeatedly accused Lincoln of advocating for full equality of blacks and whites, including not only political rights, but what was then called "amalgamation" — intermarriage between the races. Lincoln responded by saying: "Certainly the Negro is not our equal in color — perhaps not in many other respects; still, in the right to put into his mouth the bread that his own hands have earned, he is the equal of every other man. In pointing out that more has been given to you, you cannot be justified in taking away the little which has been given to him. If God gave him but little, that little let him enjoy." And: "I protest against that counterfeit logic which concludes that because I do not want a black woman for a slave, I must necessarily want her for a wife."

Note that Lincoln doesn't directly confront the racist charges of Douglas, nor does he advocate for abolition. In our time, political debate — such as it is — includes what we call negative attacks. These attacks are often based on critiques of the opponent's integrity using a standard of integrity that is all-or-nothing. In all probability, Lincoln would have failed to meet that standard. Lincoln's approach to the task of moral advancement is pragmatic. He tries to accomplish what is actually achievable at the moment. His failure to reach for the ultimate goal can be criticized for a lack of moral purity, but it did undoubtedly advance the cause. Photo courtesy U.S. Library of Congress. Photo taken February 28, 1857, by Alexander Hesler (1823-1895).

I'm often asked about how to participate in workplace politics without sacrificing one's integrity. The question itself reveals part of the problem, because it contains within it two examples of a logical fallacy called false dichotomy. With regard to politics, the confusion relates to the concept of participation; with regard to integrity, the confusion relates to the definition of integrity itself.

The basic question is this: How can I participate in workplace politics without compromising my integrity?

To begin to sort out the confusion, let's define both workplace politics and integrity. For this discussion, we take workplace politics to be what happens when we contend with each other for control or dominance, or when we work with others to resolve specific issues. We take integrity to be the alignment of word and deed with values and principles.

The definition of politics exposes the first example of false dichotomy. It is the belief that we can choose not to participate in workplace politics. That is, the question assumes that we either participate, or we don't. In reality, we cannot choose not to participate in workplace politics. Anyone employed in an organization is participating in its politics to some extent. For example, if you decide not to play an active role, you are then still a witness. Because what witnesses see and think is important to the more active participants, even witnesses play a role.

The basic question above mistakenly assumes that it's possible not to participate in workplace politics. We can choose how we participate, but we cannot choose whether we participate. Some roles are more active than others, but if you're inside the organization, you're inside its politics.

Now consider Integrity. Most of us believe that if our words, deeds, values, and principles are not in alignment, then we lack integrity. A single statement, act, principle, or value, no matter how minor, violates one's integrity if it is inconsistent with one's other words, deeds, principles, or values. Indeed, some people believe that a single such violation — no matter how incidental, or how long ago — is enough to destroy a person's integrity utterly.

This exposes the second example of false dichotomy, because perfect alignment of words, deeds, values, and principles — 100% of the time — is impossible. As human beings, we cannot choose whether we Most of us believe that

if our words, deeds,

values, and principles

are not in alignment,

then we lack integritywill violate our integrity; we can only choose how and — to some extent — how often. Since absolute integrity is unachievable, a concept of degrees of integrity is more useful. For example, "She has a lot of integrity."

The problem underlying the basic question arises when we believe first we can totally avoid political participation, and second that integrity is absolute and all-or-nothing. Out here in Reality, though, both political participation and integrity are matters of degree. Reality is a whole lot messier than our theories. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

For more about the false dichotomy, see "Think in Living Color," Point Lookout for June 26, 2002. More about logical fallacies

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Workplace Politics:

When You're the Least of the Best: II

When You're the Least of the Best: II- Many professions have entry-level roles that combine education with practice. Although these "newbies"

have unique opportunities to learn from veterans, the role's relatively low status sometimes conflicts

with the self-image of the new practitioner. Comfort in the role makes learning its lessons easier.

Reactance and Micromanagement

Reactance and Micromanagement- When we feel that our freedom at work is threatened, we sometimes experience urges to do what is forbidden,

or to not do what is required. This phenomenon — called reactance — might explain

some of the dynamics of micromanagement.

Backstabbing

Backstabbing- Much of what we call backstabbing is actually just straightforward attack — nasty, unethical,

even evil, but not backstabbing. What is backstabbing?

More Things I've Learned Along the Way: VI

More Things I've Learned Along the Way: VI- When I gain an important insight, or when I learn a lesson, I make a note. Example: If you're interested

in changing how a social construct operates, knowing how it came to be the way it is can be much less

useful than knowing what keeps it the way it is.

Exhibitionism and Conversational Narcissism at Work: I

Exhibitionism and Conversational Narcissism at Work: I- Exhibitionism is one of four themes of conversational narcissism. Behavior considered exhibitionistic

in this context is that which is intended to call the attention of others to the abuser. Here are six

examples that emphasize exhibitionistic behavior.

See also Workplace Politics for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!Beware any resource that speaks of "winning" at workplace politics or "defeating" it. You can benefit or not, but there is no score-keeping, and it isn't a game.

- Wikipedia has a nice article with a list of additional resources

- Some public libraries offer collections. Here's an example from Saskatoon.

- Check my own links collection

- LinkedIn's Office Politics discussion group