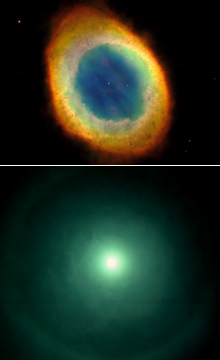

Two halos: the Ring Nebula (top) and a solar halo (bottom). The Ring Nebula (Messier 57) is a shell of ionized gas that surrounds a white dwarf star following an explosion of a red giant star. The shell is actually spherical, but it appears to us to be a ring because from this angle its edges are thickest. The solar halo is a fairly common sight that occurs when high thin clouds are positioned between the sun and the viewer. The clouds consist of tiny ice crystals oriented randomly, and rotating and moving randomly, but a tiny fraction of them at any one time are oriented just right to reflect and refract solar light at an angle of about 22 degrees. Thus, the angle between the line to the sun and the edge of the halo is exactly that angle.

These two halos are of fundamentally different kinds. The atoms of the Ring Nebula actually emit light. The ice crystals of the high thin clouds that produce the solar halo are reflecting and refracting light, the source of which is elsewhere (in this case, the sun). The Ring Nebula is an active halo, the solar halo is a passive halo. The ionized gases of the Ring Nebula are primary sources of light. The ice crystals of the solar halo are secondary sources of light. In the Halo Effect, the halo in question is passive. That is, when evaluating people, ideas, or objects, there are two kinds of attributes in question. The attributes we know and understand are the primary sources. The other attributes — the ones we get confused about — are the secondary sources. Photos of the Ring Nebula and the solar halo courtesy U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Cognitive biases are psychological phenomena that distort our perceptions, memory, or judgment. When success depends on accurate perception, evaluation, or recollection of what's around us, distortions can lead to erroneous results that range from harmless to catastrophic.

The Halo Effect (or Halo Error) was first identified in 1920 by Edward Thorndike, who was studying how military officers evaluated their subordinates. [Thorndike 1920] He found that high ratings in one attribute tended to be correlated with high ratings in other seemingly unrelated attributes. But the effect is universal, extending beyond military performance evaluation. In modern experiments, for example, researchers have demonstrated that people tend to judge physically attractive people as possessing more socially desirable personality traits than do less physically attractive people. Thus, physical traits bias our assessment of personality traits.

In the context of performance reviews, researchers have demonstrated that when evaluators perceive in subordinates attributes that they regard as negative, those evaluators tend to assess more negatively the unrelated attributes of those subordinates. This effect is known as the Horn Effect.

The Halo Effect is pervasive. Here are three examples of how it can affect organizational decision making.

- Status affects persuasiveness

- Assessments of the validity of someone's assertions can be affected by our perception of her or his status. For instance, when supervisors attend meetings of their subordinates, their statements tend to have greater weight than they deserve. And when pariahs speak, listeners are more likely to discount what is said than when superstars deliver essentially the same message.

- The effects of status are wide-ranging. For instance, someone mentored by a high-status individual can acquire some of the elevated status of the mentor. See "Dispersed Teams and Latent Communications," Point Lookout for September 3, 2003, for more.

- Falsifying an argument falsifies the assertion

- When we assess the truth of an assertion, we examine the argument that justifies it. In the course of that examination, if we find a flaw in the argument, we sometimes conclude that the assertion is false. The assertion might indeed be false, but finding a flaw in a supposed proof of the assertion doesn't prove that the assertion is false.

- This error is a rhetorical fallacy known as argumentum ad logicam, the fallacy fallacy, or the fallacist's fallacy. It's a manifestation of the halo effect in the realm of logic.

- Hat hanging

- Hat hanging is a phenomenon identified by Virginia Satir, a pioneer family therapist. When pariahs speak, listeners are

more likely to discount what is

said than when superstars deliver

essentially the same messageThe name evokes the idea that we hang the hat of someone from our past on someone in our present. For example, life can be difficult for someone whose appearance matches the appearance of a film actor who often plays villains. It's a manifestation of the halo effect in the realm of personal identification. - Hat hanging can occur in supervisor-subordinate pairs when age differences approximate parent-child age differences. See "You Remind Me of Helen Hunt," Point Lookout for June 6, 2001, for more.

Recognizing the Halo Effect in oneself is difficult. Practice by recognizing it in others. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Critical Thinking at Work:

When Stress Strikes

When Stress Strikes- Most of what we know about person-to-person communication applies when levels of stress are low. But

when stress is high, as it is in emergencies, we're more likely to make mistakes. Knowing those mistakes

in advance can be helpful in avoiding them.

I've Got Your Number, Pal

I've Got Your Number, Pal- Recent research has uncovered a human tendency — possibly universal — to believe that we

know others better than others know them, and that we know ourselves better than others know themselves.

These beliefs, rarely acknowledged and often wrong, are at the root of many a toxic conflict of long standing.

What Groupthink Isn't

What Groupthink Isn't- The term groupthink is tossed around fairly liberally in conversation and on the Web. But it's

astonishing how often it's misused and misunderstood. Here are some examples.

When Fixing It Doesn't Fix It: I

When Fixing It Doesn't Fix It: I- When complex systems misbehave, a common urge is to find any way at all to end the misbehavior. Succumbing

to that urge can be a big mistake. Here's why we succumb.

Motivation and the Reification Error

Motivation and the Reification Error- We commit the reification error when we assume, incorrectly, that we can treat abstract constructs as

if they were real objects. It's a common error when we try to motivate people.

See also Critical Thinking at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!