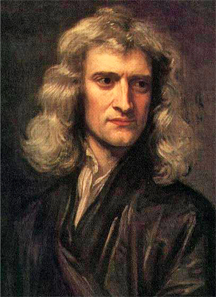

Portrait of Isaac Newton (1642-1727). This is a copy of a painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1689). Image courtesy Wikimedia.

When solving problems we sometimes reach conclusions that don't serve us well. In the less harmful cases, we discover our error before we make significant investments. In other cases, we commit resources and energy that lead only to the ends of blind alleys, compelling us to reconsider, or find alternatives, or to ultimately abandon efforts altogether. And that's if the organization survives. Human creativity ensures that we can create blind-alley "solutions" in endless variety. But one particular pattern is what I call the Newtonian Blind Alley.

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) was a natural philosopher who created many of the early models of natural phenomena: optics, gravitation, and mechanics, to name a few. He was a revolutionary, in the sense that his conclusions were based on a method of reasoning not widely used at the time, but which we now identify as scientific. His work was founded on a limited number of assumptions about how the natural world works.

Those assumptions — often called "laws" — have since permeated Western culture. Nearly everyone knows the more famous examples: "For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction." Or "A body in uniform motion tends to stay in motion unless an external force acts on it."

Unfortunately, these assumptions are routinely and often implicitly applied in domains for which there is little evidence of their relevance. And that's where the trouble begins.

For example, consider the assumption that the laws of physics are universal — so that a law that applies at Point A must necessarily apply everywhere. Newton used this assumption when he proposed his theory of gravitation, which states that the attractive force between two point masses acts along the line between them, is proportional to the product of the two masses, and is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Newton proposed that this law is universal, applying to all masses throughout the universe.

Newton's theory We assume that the laws of physics

are universal — a law that applies here

must necessarily apply everywhereserved astronomers well until definitive experiments confirmed Einstein's theory of gravitation, but the assumption of universality stands: even for Einstein's theory, we continue to assume that what holds in one place in the universe holds everywhere.

The "laws" of physics might well be universal — we have scant evidence to the contrary. But applying an analogous universality assumption to managing organizations is risky. An example of an analogous assumption might be something like, "If Re-engineering worked in six companies, it will work here." Or "If social media helped the X foundation raise the funds it needed, it will help us." Many a management initiative has failed because it was patterned after initiatives that worked well in several other organizations, without thoroughly understanding how the context, culture, and history of those organizations affected the results of the initiative.

The flaw in their reasoning is that the past efforts might have succeeded because of particular features of those organizations that aren't present in every organization, and when those features are absent, the pattern doesn't work as well, or fails utterly. When the pattern does fail, Newtonian thinking has led to another blind alley.

Misplaced belief in universality is just one example of a Newtonian Blind Alley. We'll examine another example next time. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Problem Solving and Creativity:

Poverty of Choice by Choice

Poverty of Choice by Choice- Sometimes our own desire not to have choices prevents us from finding creative solutions. Life

can be simpler (if less rich) when we have no choices to make. Why do we accept the same tired solutions,

and how can we tell when we're doing it?

When We Need a Little Help

When We Need a Little Help- Sometimes we get in over our heads — too much work, work we don't understand, or even complex

politics. We can ask for help, but we often forget that we can. Even when we remember, we sometimes

hold back. Why is asking for help, or remembering that we can ask, so difficult? How can we make it easier?

Knowing Where You're Going

Knowing Where You're Going- Groups that can't even agree on what to do can often find themselves debating about how

to do it. Here are some simple things to remember to help you focus on defining the goal.

Workplace Politics and Type III Errors

Workplace Politics and Type III Errors- Most job descriptions contain few references to political effectiveness, beyond the fairly standard

collaborate-to-achieve-results kinds of requirements. But because true achievement often requires political

sophistication, understanding the political content of our jobs is important.

Strategic Waiting

Strategic Waiting- Time can be a tool. Letting time pass can be a strategy for resolving problems or getting out of tight

places. Waiting is an often-overlooked strategic option.

See also Problem Solving and Creativity for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!