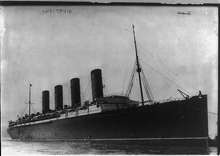

Cunard's R.M.S. Lusitania coming into port, possibly in New York. The passenger liner was sunk by a German U-Boat early in World War I, on May 7, 1915. At the time, she was carrying 1,959 passengers and crew, 1,198 of whom were killed. She sank within 18 minutes of being struck. Her sinking was viewed by many as what we now call a war crime, and it led to the entry of the United States into the war.

During the investigation that followed, investigators encountered many of the obstacles to truth-finding that are listed here. The question of the number of torpedoes provides an example of fabrication. One torpedo was deployed, but since two torpedoes would deflect responsibility for loss of life away from Cunard and the ship designers, witnesses were pressured to report two torpedoes. An example of concealment was the withholding of information about the ammunition cargo that the ship carried. Explosive cargo might have been identified as a reason for the rapid sinking. Photo from the George Grantham Bain Collection (U.S. Library of Congress).

Following unwanted outcomes, we often commission "lessons learned" exercises to investigate the conditions that brought about the unwanted outcomes. We want to learn how to prevent recurrences of those outcomes or any other unwanted outcomes that might flow from similar conditions. In too many organizations, these exercises yield useless or misleading results.

What we seek is Truth: the reasons why the unwanted outcome occurred. But these investigations rely on reports from people who participated in or witnessed events leading to the outcome. To find the truth we must interpret the reports we receive, and those reports can contain a variety of misleading elements. Here's a short catalog of those elements.

- Confusions and mistakes

- Relying on memory and impressions, witnesses and participants sometimes get it wrong. They get confused about the order of events, or who did what. They confuse what they actually witnessed with what they heard about second-hand.

- Excuses

- An excuse is a fact, condition, or situation that provides protection for someone from blame for the unwanted outcome. Excuses are those offerings that, if true, most people would accept as relieving someone of being regarded as having caused or contributed to causing the unwanted outcome.

- Allegations

- An allegation is the opposite of an excuse — it's a fact, condition, or situation that, if true, affixes to someone blame for the unwanted outcome. While excuses tend to be offered by the person excused, allegations tend to be offered by someone other than the one blamed.

- Omissions

- Reports that omit relevant information can also mislead investigators. Omissions can be intentional, but they need not be. They can result from numerous factors including faulty memory, emotional trauma, and poor technique by the investigator.

- Concealment

- Concealment To find the truth we must

interpret reports that can

contain a variety of

misleading elementstranscends intentional omission. It includes deliberate actions to deflect the investigator from the information concealed, such as destruction or obfuscation of information, or propagating false accounts of events. It can also include actions that make the information difficult to retrieve. For example, important witnesses might be relocated, terminated, or transferred. - Fabrications

- Fabrications are fictions intended to mislead the investigator. When well crafted and when delivered by someone who is unaware that they are fabrications, they are difficult to detect, because the deliverer isn't actually lying. Detecting them often requires tracing them to their source.

In determining who acted (or did not act) so as to contribute to the genesis of the unwanted outcome, there's a high risk that some witnesses and participants might experience the investigation as a search for someone to blame. The investigators themselves might adopt this belief.

In organizational cultures that tend to affix blame, investigations are unlikely to uncover much Truth, because people fear blame. Over time, people who don't master these tools for misleading investigations tend to be discredited, ejected from the organization, or allocated to less central roles. Organizations that want to improve outcomes would do well to eliminate blame from their cultures. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are you fed up with tense, explosive meetings? Are you or a colleague the target of a bully? Destructive conflict can ruin organizations. But if we believe that all conflict is destructive, and that we can somehow eliminate conflict, or that conflict is an enemy of productivity, then we're in conflict with Conflict itself. Read 101 Tips for Managing Conflict to learn how to make peace with conflict and make it an organizational asset. Order Now!

For indicators that an organizational culture is a blaming culture, see "Top Ten Signs of a Blaming Culture," Point Lookout for February 16, 2005. The words blame and accountability are often used interchangeably, but they have very different meanings. See "Is It Blame or Is It Accountability?," Point Lookout for December 21, 2005, for a discussion of blame and accountability. For more on blaming and blaming organizations, see ":wrapquotes" and "Plenty of Blame to Go Around," Point Lookout for August 27, 2003.

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Organizational Change:

Kinds of Organizational Authority: the Informal

Kinds of Organizational Authority: the Informal- Understanding Power, Authority, and Influence depends on familiarity with the kinds of authority found

in organizations. Here's Part II of a little catalog of authority, emphasizing informal authority.

How to Find Lessons to Learn

How to Find Lessons to Learn- When we conduct Lessons Learned sessions, how can we ensure that we find all the important lessons to

be learned? Here's one method.

Motivation and the Reification Error

Motivation and the Reification Error- We commit the reification error when we assume, incorrectly, that we can treat abstract constructs as

if they were real objects. It's a common error when we try to motivate people.

Organizational Roots of Toxic Conflict

Organizational Roots of Toxic Conflict- When toxic conflict erupts in a team, cooperation ends and person-to-person attacks begin. Usually we

hold responsible the people involved. But in some cases, the organization is the root cause, and then

replacing or disciplining the people might not help.

Way Over Their Heads

Way Over Their Heads- For organizations in crisis, some but not all their people understand the situation. Toxic conflict

can erupt between those who grasp the problem's severity and those who don't. Trying to resolve the

conflict by educating one's opponents rarely works. There are alternatives.

See also Organizational Change for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!