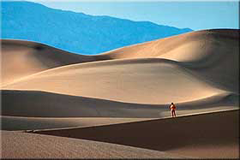

Dunes in Death Valley, California. Dunes are of course transitory, moved about constantly by wind action. At the time of this photograph, we can see several possible "hill peaks" of the kind we imagine when we use hill climbing algorithms. Looking at the photo, it's easy to understand how hill climbing algorithms can be captured by local maxima, thereby preventing them from finding even higher maxima. Photo courtesy U.S. National Park Service.

Finding the extreme values of functions is a common problem in mathematics. For instance, one form of the famous "traveling salesman" problem involves finding the shortest path that a traveling salesman can follow to visit all customers in a given district. Algorithms for optimizing functions are called "hill climbing" algorithms if they work by gradually improving a solution, adjusting its attributes one at a time.

The hill climbing metaphor comes from imagining the function's value as being the altitude of a point in a geographical region. To find the highest point in the region, we take one step at a time, always uphill. By always climbing uphill, we hope that we'll find the highest point in the region. The metaphor is so powerful that hill climbing algorithms are called "hill climbing" even when we're minimizing something instead of maximizing.

There's just one problem: hill climbing doesn't always work. For example, suppose you're unlucky enough to start your optimizing on the shoulder of a hill that happens to be the second-highest hill in the region. By always "moving uphill" you will indeed find the peak of that second-highest hill, but you'll never find the highest hill. In effect, the algorithm is "captured" by the second-highest hill and it can't break free.

That's unfortunate, because we use hill climbing often without being aware of it. For instance, when we hire people, we look for attributes that we feel will ensure that we hire the best. One such attribute is experience in efforts exactly like the ones we anticipate. Even though identical experience doesn't necessarily ensure future success, we use experience because we believe that it will take us most steeply "uphill." It's possible, of course, that someone with a different experience background might be just what we need to achieve even better results. But we'll never know, because the current solution has captured us.

This In decision making, we use hill

climbing often without being

aware of ithappens in problem solving too. When we're familiar with one solution, we tend to focus on filling out the rest of that solution, rather than seeking a completely new approach that might lead to a far better solution. Such new approaches are sometimes said to arise from "thinking out of the box."

And most tragically, hill climbing can lead to the downfall of an entire enterprise. A company that's dominant in its market can become captured by the particular way in which it meets customer needs. Even though it searches constantly for innovations, it seeks only those innovations that preserve certain attributes of its current offerings. When a competitor enters the market with a wholly different approach, that competitor can prevail if its solution gives the customer a path to a "higher hill." Think airlines and railroads, iTunes and record stores, or iPhone and Blackberry.

Is your enterprise captured by a hill climbing approach? Maybe it's not too late to do something about it. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness:

There Is No Rumor Mill

There Is No Rumor Mill- Rumors about organizational intentions or expectations can depress productivity. Even when they're factually

false, rumors can be so powerful that they sometimes produce the results they predict. How can we manage

organizational rumors?

Who Would You Take With You to Mars?

Who Would You Take With You to Mars?- What makes a great team? What traits do you value in teammates? Project teams can learn a lot from the

latest thinking about designing teams for extended space exploration.

Virtual Interviews: I

Virtual Interviews: I- The pandemic has made face-to-face job interviews less important. Although understanding the psychology

of virtual interviews helps both interviewers and candidates, candidates would do well to use the virtual

interview to demonstrate video presence.

Subject Lines for Intra-Team Messages

Subject Lines for Intra-Team Messages- When teams communicate internally using messaging systems like email, poorly formed subject lines of

messages can limit the effectiveness of the exchanges. Subject lines therefore provide a powerful means

of increasing real-time productivity of the team.

Improvement Bias

Improvement Bias- When we set about improving how our organizations do things, we expose ourselves to the risk of finding

opportunities for improvement that offer very little improvement, while we overlook others that could

make a real difference. Cognitive biases play a role.

See also Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!