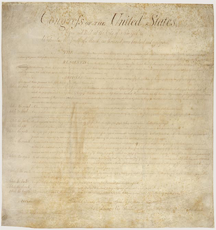

The Bill of Rights — the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The Bill actually was a Bill, introduced in the First Congress, and sent on after much wrangling, to the states for ratification. How it came about is a wonderful illustration of the approach to impasse that is founded on acceptance and serious consideration of the views of dissenters. Ratification of the Constitution was a controversial decision, with two views contending for dominance. The dominant group were the Federalists, who favored a strong central government and who felt that no enumeration of rights was advisable. The dissenting minority were the Anti-Federalists, who were wary of strong central government and who wanted specific protection of individual rights. Ratification of the Constitution met serious opposition in some states, including in Massachusetts. But it succeeded there based on an approach that came to be known as the Massachusetts Compromise, which enabled Anti-Federalists to vote to ratify the Constitution in exchange for a commitment by Federalists to consider the amendments that would become the Bill of Rights. This compromise was replicated in other states where ratification was problematic, and on September 13, 1788, the Constitution was finally declared ratified, albeit at that time by only 11 of the thirteen states that eventually ratified it.

The first Congress met in New York City on March 4, 1789, dominated by the Federalists, 20 to 2 in the Senate, and 48 to 11 in the House. It was this First Congress that adopted and sent to the states for ratification the Bill of Rights, which dealt specifically with the Anti-Federalists' objections. Read more about the history of the Bill of Rights. Photo courtesy .

We began an exploration of impasses last time by focusing on the perspective of opinion minorities. In our scenario, we postulated that the group did have consensus on some issues, which we called the C-Issues. But there was disagreement on other issues — the D-Issues. In this Part II, we explore two tactics that tend to strengthen the impasse, preventing agreement.

- Hostage tactics

- Some group members believe that by taking hostages, they can compel the rest of the group to adopt a position more to their liking. The hostage of choice is often one or more of the C-Issues. In the view of the hostage takers, refusing to agree to the C-Issues exerts pressure on the rest of the group to comply with the hostage-takers' wishes. This tactic can become corrosive if members of the rest of the group press the hostage-takers to justify their opposition to the hostage C-Issues. The hostage-takers then devise arguments to justify their opposition to the C-Issues, which, often, they themselves don't believe. What little agreement there was with respect to C-Issues might then vanish. Even worse, others in the group might become intransigent, if they feel that acceding to the hostage-takers' demands will only invite further demands and further hostages, either by the hostage-takers or by others who witness the success of the hostage-takers.

- Acceding to hostage-takers' demands might seem appealing, but it does usually lead to more widespread hostage taking. Because questioning the hostage-takers about C-Issues risks converting C-Issues to D-Issues, approaches to forging agreement must always focus on D-Issues. Make the concerns of the objectors visible, and deal with them substantively.

- Abuse of the concept of precedent

- Some group members might fear that after they agree to the C-Issues, they won't be able to influence subsequent decisions sufficiently with respect to the D-Issues. They see partial agreement as the first step on a slippery slope, fearing that others will use their partial agreement as inappropriate leverage for later decisions. In effect, they fear they might be confronted with, "I don't see what your problem is with D-Issue #3, because you agreed to C-Issue #2." That tactic can indeed be an abuse of the concept of precedent, if it relies solely on the fact of agreeing to C-Issue #2, rather than on the substance of C-Issue #2, the substance of D-Issue #3, and their connection.

- If abuse of precedent Acceding to hostage-takers' demands

might seem appealing, but it does

usually lead to more

widespread hostage-takinghas occurred in the past, then certainly the concern is real, and the group must deal with it. To address the concern, the group can agree that such content-free appeals to precedents are unacceptable.

Hostage-taking by dissenters, or precedent abuse by those pressuring dissenters, are indirect attempts to gain adherents. To avoid strengthening impasses, deal directly with objections to agreement. First in this series Next in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are you fed up with tense, explosive meetings? Are you or a colleague the target of a bully? Destructive conflict can ruin organizations. But if we believe that all conflict is destructive, and that we can somehow eliminate conflict, or that conflict is an enemy of productivity, then we're in conflict with Conflict itself. Read 101 Tips for Managing Conflict to learn how to make peace with conflict and make it an organizational asset. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Conflict Management:

How to Avoid Responsibility

How to Avoid Responsibility- Taking responsibility and a willingness to be held accountable are the hallmarks of either a rising

star in a high-performance organization, or a naïve fool in a low-performance organization. Either

way, you must know the more popular techniques for avoiding responsibility.

What You See Isn't Always What You Get

What You See Isn't Always What You Get- We all engage in interpreting the behavior of others, usually without thinking much about it. Whenever

you notice yourself having a strong reaction to someone's behavior, consider the possibility that your

interpretation has outrun what you actually know.

On Snitching at Work: II

On Snitching at Work: II- Reporting violations of laws, policies, regulations, or ethics to authorities at work can expose you

to the risk of retribution. That's why the reporting decision must consider the need for safety.

Backstabbing

Backstabbing- Much of what we call backstabbing is actually just straightforward attack — nasty, unethical,

even evil, but not backstabbing. What is backstabbing?

Covert Verbal Abuse at Work

Covert Verbal Abuse at Work- Verbal abuse at work uses written or spoken language to disparage, disadvantage, or harm others. Perpetrators

favor tactics they can subsequently deny having used. Even more favored are abusive tactics that are

so subtle that others don't notice them.

See also Conflict Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!