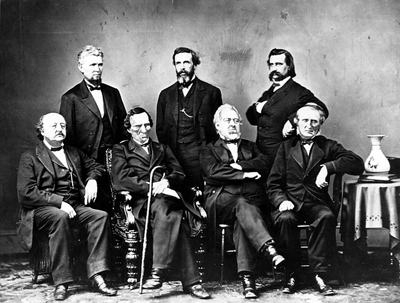

The impeachment managers for the impeachment of U.S. President Andrew Johnson, 1868. View a larger image. Standing are James Falconer Wilson (R-Iowa 1st), George Sewall Boutwell (R-Massachusetts 7th), and John Alexander Logan (R-Illinois at-large). Seated are Benjamin Franklin Butler (R-Massachusetts 5th at the time), Thaddeus Stevens (R-Pennsylvania 9th), Thomas Williams (R-Pennsylvania 23rd), and John Armor Bingham (R-Ohio 16th). Thaddeus Stevens, a Radical Republican, is the character to whom President Lincoln tells the "True North" story in the recent film, Lincoln. Lincoln wanted to persuade Stevens to argue more moderately in favor of the 13th Amendment, because he felt that a more ideological argument would result in failure. Paraphrasing Lincoln's line in the film, "A compass will point you true North. But it won't show you the swamps in between you and there. If you don't avoid the swamps, what's the use of knowing true North?" Essentially, Lincoln is arguing for a pragmatic approach in preference to a more ideological one.

The line is likely invented by the filmmakers. I know of no evidence that Lincoln actually employed such a metaphor. Nevertheless, it is a powerful illustration of the interplay between the objective orientation and the obstacle orientation. Success demands both.

Photo by Mathew Brady, in the United States Signal Corps, War Department, Washington, 1868. Available from Wikipedia.

People have preferences. We have preferences about so many different things that the number of different combinations is enormous. Everyone is unique. We even have preferences about the ways we try to solve problems. One classification of problem-solving preferences is the relative interest we have in focusing on objectives versus obstacles.

To focus on objectives is to keep foremost in mind what we're trying to achieve by solving the problem. To focus on obstacles is to look first at the difficulties we face when we try to implement candidate solutions.

When we approach problem solving, few of us are aware of whether we prefer to focus on objectives or obstacles. And few of us make conscious choices of focus during the solution process.

Because solving problems successfully requires balanced attention to both objectives and obstacles, choosing the right focus at the right stage of problem solving can dramatically enhance problem-solving effectiveness. Here are some observations that can help you make wise choices.

- Objective orientation

- A focus on objectives helps us find the way to the goal when we must make the detours needed to evade or eliminate obstacles. Keeping objectives in mind can be inspiring when attaining them seems out of reach, or when we encounter obstacles wherever we turn.

- The objective orientation has a dark side, too. It can lead to an obsession with ideas that seem promising, but which have little practical value. And it can lead us to reject out of hand any candidate solution that requires that we temporarily deviate from the direct path to our goal. Rigid adherence to the objective orientation can actually prevent us from finding ways around obstacles.

- Obstacle Orientation

- A focus on obstacles helps us find impediments Relying mostly on one approach —

either objectives or obstacles — to

the exclusion of the other is a

path to failureearly in the search for solutions. This enables wise allocation of resources, which helps us rank possible solutions according to likelihood of success. And when we notice a common theme among some of the obstacles we find early in the search, we can apply that insight to the task of generating more promising candidate solutions. - The obstacle orientation has a dark side, too. A focus on obstacles can be dispiriting, because we must search for reasons why candidate solutions don't work. Sometimes we must consider the question, "Can any solution at all ever work?" And sometimes we can become so lost in addressing obstacles that we lose sight of the objective.

Relying mostly on one approach to the exclusion of the other is a path to failure. Both orientations — objectives and obstacles — are needed at various times and in different situations. And often we can't tell which approach we need at any given moment. An appreciation for the advantages and risks associated with each perspective can lead to acceptance of the approaches and contributions of people whose preferences differ from our own. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Occasionally we have the experience of belonging to a great team. Thrilling as it is, the experience is rare. In part, it's rare because we usually strive only for adequacy, not for greatness. We do this because we don't fully appreciate the returns on greatness. Not only does it feel good to be part of great team — it pays off. Check out my Great Teams Workshop to lead your team onto the path toward greatness. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Problem Solving and Creativity:

Bois Sec!

Bois Sec!- When your current approach isn't working, you can scrap whatever you're doing and start again —

if you have enough time and money. There's a less radical solution, and if it works, it's usually both

cheaper and faster.

Unintended Consequences

Unintended Consequences- Sometimes, when we solve problems, the solutions create new problems that can be worse than the problems

we solve. Why does this happen? How can we limit this effect?

Reactance and Decision Making

Reactance and Decision Making- Some decisions are easy. Some are difficult. Some decisions that we think will be easy turn out to be

very, very difficult. What makes decisions difficult?

When Fixing It Doesn't Fix It: I

When Fixing It Doesn't Fix It: I- When complex systems misbehave, a common urge is to find any way at all to end the misbehavior. Succumbing

to that urge can be a big mistake. Here's why we succumb.

Contributions, Open and Closed

Contributions, Open and Closed- We can classify contributions to discussions according to the likelihood that they stimulate new thought.

The more open they are, the more they stimulate new thought. How can we encourage open contributions?

See also Problem Solving and Creativity for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!