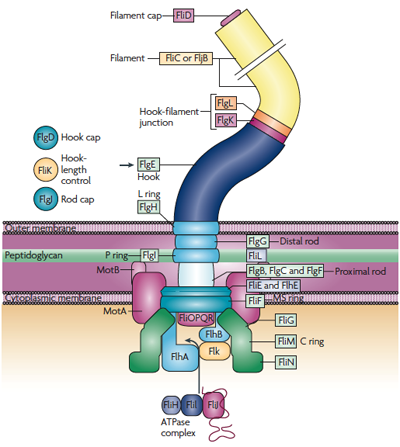

A schematic representation of the flagellar components of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, in cross-section. View a larger image. The flagellum, which provides locomotion for the bacterium, is a long helical structure that is shown in abbreviated form at the top of the drawing. Locomotion is achieved by rotating the flagellum. The apparatus at the bottom of the figure, shown in cross-section, is the motor. The motor is approximately 150 Å in diameter. For reference, an oxygen molecule is approximately 3 Å in diameter.

The structure itself is a marvel, but even more wondrous is the process by which it is built. That process is the topic of the paper from which this figure is drawn. As described by F.F. Chevance and K.T. Hughes, the proteins required are manufactured within the cell, and passed along the portions of the apparatus that have so far been assembled. As the different components are completed, chemical signals are fed back to the cell with instructions for what proteins are needed next, and what proteins are no longer needed. This complex choreography is a sequence of messages — requests and responses — that results in a complete motor and flagellum.

The sequence of requests and responses that builds a flagellum and motor would fail utterly if any element of the system decided to over-deliver. That is, if, say, the cell body decided to anticipate the needs of the flagellum under construction, it would deliver proteins that could not yet be used. Or, if used, they would clutter the "construction site," resulting in malformations and a nonfunctional motor assembly or flagellum. Nature and evolution have solved this problem by inhibiting over-deliveries of the kind discussed here. People in organizations must learn to do the same.

The image is from Chevance F.F. and Hughes K.T. "Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine." Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008,6:455-465.

When asked a question such as "Is that correct?" some of us embark on paths that create trouble in our working relationships. For example, suppose Jan knows that the premise isn't correct, because she knows of at least one counterexample — call it X. Instead of responding, "No, it isn't correct, because of X," she begins forming a mental catalog of all possible counterexamples. If Jan receives the query in conversation, she pauses while she assembles her response. If she receives the query in email, she takes a day or two to do research.

That's why it takes Jan longer to respond than the person who asked the question expects. Often, people interpret these delays as shiftiness, evasiveness, or secretiveness. They might see her as being careful in her words, or plotting, or scheming, or taking time to manufacture lies or misleading responses, or lacking in confidence.

Questioners who fairly evaluate her responses are much less likely to make these erroneous conclusions. But some questioners don't want the complete responses Jan always delivers. Questioners who ask, "Is that correct" sometimes don't want a full catalog of the reasons why it isn't correct, and they ignore it when she delivers it. Their preferences thus lead them to misunderstand what takes Jan so long to respond.

By over-delivering, some people, like Jan, convey the impression of being untrustworthy, scheming, reluctant, or incompetent.

To avoid this problem, apply a general principle:

When asked for an opinion or judgment, and the request doesn't specify a need for a complete or absolutely reliable response, a partial and estimated response — delivered right now — might suffice. If you're unsure, deliver the short answer, then ask.

Some examples:

- Is this possible?

- If you know one reason why it's impossible, that might be enough. Offer it and ask if more are needed.

- Can you do it by Friday?

- One reason why you can't might be enough.

- Why is that so?

- If you know one possible explanation, provide it, acknowledging that it isn't 100% certain or complete.

- Who do you think can do this?

- This is a question about capability, not availability. A complete list might not be required.

- Can we do this for under $X?

- This just requires a By over-delivering, some people

convey the impression of being

untrustworthy, scheming,

reluctant, or incompetentyes-or-no answer. Yes can require significant research. No can be very easy. - Who told you that? Or: Where did you hear that?

- A complete list isn't required. It might not be necessary to provide the date on which you were told, or the order in which various people told you.

- Would any changes be required to meet that requirement?

- If you know of one, then the answer is yes. You don't necessarily need to devise a complete, priority-ranked or cost-ranked list of all changes that would be required.

And I don't think I need to supply any more examples. You get the idea. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are you fed up with tense, explosive meetings? Are you or a colleague the target of a bully? Destructive conflict can ruin organizations. But if we believe that all conflict is destructive, and that we can somehow eliminate conflict, or that conflict is an enemy of productivity, then we're in conflict with Conflict itself. Read 101 Tips for Managing Conflict to learn how to make peace with conflict and make it an organizational asset. Order Now!

See "How to Create Distrust," Point Lookout for May 18, 2011, for a catalog of other behaviors that erode trust.

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Effective Communication at Work:

See No Evil

See No Evil- When teams share information among themselves, they have their best opportunity to reach peak performance.

And when some information is withheld within an elite group, the team faces unique risks.

Changing the Subject: II

Changing the Subject: II- Sometimes, in conversation, we must change the subject, but we also do it to dominate, manipulate, or

assert power. Subject changing — and controlling its use — can be important political skills.

What We Don't Know About Each Other

What We Don't Know About Each Other- We know a lot about our co-workers, but we don't know everything. And since we don't know what we don't

know, we sometimes forget that we don't know it. And then the trouble begins.

Cognitive Biases and Influence: I

Cognitive Biases and Influence: I- The techniques of influence include inadvertent — and not-so-inadvertent — uses of cognitive

biases. They are one way we lead each other to accept or decide things that rationality cannot support.

Formulaic Utterances: III

Formulaic Utterances: III- Formulaic utterances are phrases that follow a pre-formed template. They're familiar, and they have

standard uses. "For example" is an example. In the workplace, some of them can help establish

or maintain dominance and credibility. Some do the opposite.

See also Effective Communication at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!