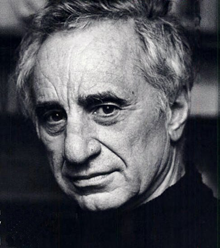

Elia Kazan (1909-2003), award winning film director. Among his films are A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), On the Waterfront (1954), and East of Eden (1955). In 1952, he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee as a so-called "friendly witness." He provided to the committee the names of artists then employed in film and theater, and whom he had met during his days as a member of the American Communist Party in New York. His testimony led to the destruction of numerous careers. More.

Photo courtesy Wikipedia.

We learn about snitching as children, often at home, when siblings practice it on each other, or in our early years at school. By whatever name, snitching, tattling, ratting, or finking is the act of informing authority about an alleged transgression by a third party, usually a peer. And again as children, we learn that the practice is deprecated. Those who snitch are sometimes ostracized or socially penalized in a variety of ways. To most children, snitching — all snitching — is bad.

But that's the child's view. Children have difficulty with nuance. To children, things tend to fall into two categories: good and bad. We're adults now, and we can do a little better.

Let's use neutral terms to help us in the discussion. In place of "snitching", I prefer "reporting." The person reporting is the reporter or witness. What's being reported is the offense. The person who's alleged to have committed the offense is the accused. The report recipient is the authority.

Even when the offense is real and the report would be truthful, deciding whether to report it to authority can be difficult. Let's examine the issues.

- How serious is the offense?

- If the offense is serious enough, reporting it is probably not a social transgression. What "serious enough" means is up to you, but most crimes are serious enough, certainly. Also serious are fraudulent absenteeism, false reports about work in progress, ethical violations, and violations of regulations.

- Indeed, if the offense is serious enough, If the offense is serious enough,

reporting it might be obligatory,

even if the offense isn't

a crime or ethical breachreporting it might be obligatory, even if the offense isn't a crime or ethical breach. For example, if a co-worker's performance is far enough below standards, reporting it might be an expected part of your own performance. - One useful test: if the authority finds out somehow that I knew about the offense and chose not to report it, will I be in trouble? If so, then the offense is probably "serious enough."

- Isn't all reporting antisocial?

- If the primary purpose of the report is to benefit not the organization, but the reporter or someone else, then the report might be a social transgression. For example, some people report offenses to ingratiate themselves with authorities.

- If the primary purpose of the report is to harm the accused or someone else, then the report might be a social transgression. For example, some people report transgressions because they seek revenge against the accused, or because the accused is a rival for a promotion or a plum assignment. Some seek to harm the supervisor of the accused, or the spouse of the accused. The accused might be merely a proxy for someone else.

- One general principle: a report is most likely to constitute a social transgression if its primary purpose is to benefit the reporter, or to harm someone else.

We'll continue this exploration next time, focusing on retribution. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Workplace Politics:

Using Indirectness at Work

Using Indirectness at Work- Although many of us value directness, indirectness does have its place. At times, conveying information

indirectly can be a safe way — sometimes the only safe way — to preserve or restore

well-being and comity within the organization.

When It's Just Not Your Job

When It's Just Not Your Job- Has your job become frustrating because the organization has lost its way? Is circumventing the craziness

making you crazy too? How can you recover your perspective despite the situation?

The Artful Shirker

The Artful Shirker- Most people who shirk work are fairly obvious about it, but some are so artful that the people around

them don't realize what's happening. Here are a few of the more sophisticated shirking techniques.

Stone-Throwers at Meetings: I

Stone-Throwers at Meetings: I- One class of disruptions in meetings includes the tactics of stone-throwers — people who exploit

low-cost tactics to disrupt the meeting and distract all participants so as to obstruct progress. How

do they do it, and what can the meeting chair do?

Commenting on the Work of Others

Commenting on the Work of Others- Commenting on the work of others risks damaging relationships. It can make future collaboration more

difficult. To be safe when commenting about others' work, know the basic principles that distinguish

appropriate and inappropriate comments.

See also Workplace Politics for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!Beware any resource that speaks of "winning" at workplace politics or "defeating" it. You can benefit or not, but there is no score-keeping, and it isn't a game.

- Wikipedia has a nice article with a list of additional resources

- Some public libraries offer collections. Here's an example from Saskatoon.

- Check my own links collection

- LinkedIn's Office Politics discussion group