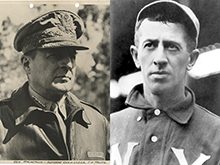

Gen. Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964, left) and Willie Keeler (1872-1923, right). Keeler was a right fielder in Major League Baseball who played from 1892 to 1910. He was one of the best hitters of his era, and is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He is famous for having advised hitters to "Keep your eye clear, and hit 'em where they ain't," with they referring to the defending fielders. During World War II, Gen. MacArthur commanded a campaign in the southwest Pacific in which he avoided the heavy losses that would have been inevitable if he had attacked enemy strong points. Instead, he cut their supply lines at points less strongly defended. In describing this strategy, he often cited Wille Keeler's advice to "hit 'em where they ain't." (See William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880-1964, New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1978.)

Photo of Willie Keeler ca. 1903, available at Wikipedia. Photo of Gen. MacArthur courtesy U.S. National Archives.

We began our catalog of risk management strategies last time, exploring Denial, Shock, Acceptance, and Chaos. None of those four are particularly effective with respect to achieving our goals in the context of adversity. One more ineffective strategy remains to be explored before we examine some more effective approaches.

- Procrastination

- This strategy, usually executed unconsciously, involves repeated delay of planning to address acknowledged risks. We just can't seem to find time to sit down and plan for risks.

- Slogan: "Yes, we have to plan for that risk, but we're too busy right now. Maybe tomorrow."

- Advantage: Deferring planning enables the procrastinator to defer acknowledging the cost of managing risk, which can be helpful in persuading decision makers to undertake or continue the effort, because its full cost is unrecognized. Procrastinating also enables the procrastinator to claim that planning is "in progress" when actually it isn't.

- Danger: Procrastinating leads to a perception that the resources at hand are sufficient, when they might be wholly inadequate. It can also lead to delays so great that the organization can become unable to prepare for the risk prior to the actual risk event.

Let's look now at strategies that actually facilitate progress.

- Avoidance

- Avoidance is the choice to eliminate the possibility of loss by changing what you're doing. Other losses might happen, but not that one. For example, if we include an overview of the Marigold project in our presentation, we risk being asked about Issue 18, for which we have no answers yet. To avoid that risk, we decide not to provide a general overview of Marigold. Instead we'll discuss only Issue 17, which is almost resolved.

- Slogan: "If we use this other design instead, we can avoid that risk."

- Advantage: Finding Sometimes we can be so averse

to risk that we convince ourselves

that a risk-avoiding alternative

approach can achieve our goals,

when it actually cannota clever alternative to what we planned originally, and thereby avoiding a risk we would have borne under the original approach, can be both elegant and effective. - Danger: Sometimes we can be so averse to risk that we convince ourselves that a risk-avoiding alternative approach can achieve our goals, when it actually cannot.

- Limitation

- Limitation strategies reduce the probability of the risk event occurring, or reduce the size of the loss if it does occur, or both. Using limitation, we make the risk acceptable by reducing the expected value of the loss.

- Slogan: "We can reduce the probability of that risk (or the cost of that risk) if we do this."

- Advantage: The expected value of the loss associated with a risk event is the product PV, where P is the probability of the occurrence and V is the value lost. If we can reduce the expected value enough, we can proceed with confidence, even if the risk event occurs.

- Danger: Estimating probabilities is notoriously difficult. If we're wrong in our estimates, and the risk event occurs, we could be in trouble.

We'll continue next time with the last three of our risk management strategies. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Projects never go quite as planned. We expect that, but we don't expect disaster. How can we get better at spotting disaster when there's still time to prevent it? How to Spot a Troubled Project Before the Trouble Starts is filled with tips for executives, senior managers, managers of project managers, and sponsors of projects in project-oriented organizations. It helps readers learn the subtle cues that indicate that a project is at risk for wreckage in time to do something about it. It's an ebook, but it's about 15% larger than "Who Moved My Cheese?" Just . Order Now! .

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Quantum Management

Quantum Management- When we plan projects, we estimate the duration and cost of something we've never done before. Since

projects are inherently risky, our chances of estimating correctly are small. Quantum Management tells

us how to think about cost and schedule in new ways.

Nine Positive Indicators of Negative Progress

Nine Positive Indicators of Negative Progress- Project status reports rarely acknowledge negative progress until after it becomes undeniable. But projects

do sometimes move backwards, outside of our awareness. What are the warning signs that negative progress

might be underway?

How to Make Good Guesses: Tactics

How to Make Good Guesses: Tactics- Making good guesses probably does take talent to be among the first rank of those who make guesses.

But being in the second rank is pretty good, too, and we can learn how to do that. Here are

some tactics for guessing.

The Risks of Too Many Projects: II

The Risks of Too Many Projects: II- Although taking on too many projects risks defocusing the organization, the problems just begin there.

Here are three more ways over-commitment causes organizations to waste resources or lose opportunities.

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II- Plans are well known for working out differently from what we intended. Sometimes, the unintended outcome

is due to external factors over which the planning team has little control. Two examples are priming

effects and widely held but inapplicable beliefs.

See also Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!