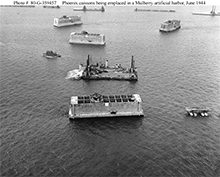

Phoenix caissons being towed to form a Mulberry harbor off Normandy, June 1944. The Normandy coast has few natural harbors, and for that reason, among others, the German command regarded it as an unlikely site for a landing. They expected an assault at or near one of the harbors on the French coast, which they therefore fortified heavily. Recognizing the high risk of an attack at or near a harbor, the Allies chose to transform that risk into the risks associated with a beach landing. They then dealt with those risks, in part, by engineering artificial harbors, constructed from chains of caissons like those shown here, which they towed from the English coast and sank off the beaches of Normandy. This approach is a clear example of risk transformation. Photo courtesy U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command.

In Part I and Part II, we explored five ineffective strategies and two somewhat more effective strategies for managing risk. In this Part III, we complete our little catalog with three of the more effective strategies.

- Transformation

- Transformation strategies entail exchanging the risk or risks in question for a different risk or risks. After the transformation, the asset at risk might be different, or it might be imperiled in a different way, or both. For example, if we're traveling from A to B, and two routes are available, Route 1 might be more congested, while Route 2 might be more hazardous. If we take Route 1 we might lose time; if we take Route 2 we might lose the vehicle and its passengers.

- Slogan: "That risk vanishes if we use this alternative approach, but then we would have to deal with this other risk instead."

- Advantage: If we can't deal with risk event A, but we can deal with risk event B, then we can proceed with confidence if we take an approach in which risk event A cannot occur, but risk event B might.

- Danger: Dealing with risk usually entails estimation. Our estimates can be wrong, either because of the errors inherent in estimation, or because we mislead ourselves.

- Compensation

- In compensation strategies, we arrange that if the risk event occurs, we make up for it somehow.

- Slogan: "If we take these steps, then these good things will happen if the risk materializes."

- Advantage: In compensation strategies, we

arrange that if the risk event

occurs, we make up

for it somehowEven if we can't sufficiently limit the probability or size of the loss, we can proceed with confidence, because the net value of the compensation minus the expected value of the loss is acceptable. - Danger: We might be so emotionally committed to proceeding that we overestimate the value of the compensation.

- Transfer

- In transfer strategies, we arrange to have some other person or organization (the counter party) bear the consequences of the risk. When the transfer is by mutual agreement, the parties usually exchange some resources as well. Purchasing insurance is an example of a risk transfer strategy.

- Slogan: "If we do this, then we don't have to deal with that risk. They will."

- Advantage: Transferring risk to another party can relieve us of the burden of planning for the risk. The sum of both the resources required for such planning and the expected value of the loss can exceed the cost of transferring the risk.

- Danger: The counter party might not be strong enough, or ethical enough, to cover the loss. When counter parties are coerced into accepting the risk, their reliability can be dubious. Be certain that the transfer is real.

Project risk is inherently imprecise, both numerically and conceptually. By far, the greatest risk is the risk of overlooking or misunderstanding a significant risk, including this one. Ironically, I have never seen it mentioned in a risk plan. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Projects never go quite as planned. We expect that, but we don't expect disaster. How can we get better at spotting disaster when there's still time to prevent it? How to Spot a Troubled Project Before the Trouble Starts is filled with tips for executives, senior managers, managers of project managers, and sponsors of projects in project-oriented organizations. It helps readers learn the subtle cues that indicate that a project is at risk for wreckage in time to do something about it. It's an ebook, but it's about 15% larger than "Who Moved My Cheese?" Just . Order Now! .

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Seeing Through the Fog

Seeing Through the Fog- When projects founder, we're often shocked — we thought everything was moving along smoothly.

Sometimes, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that we had — or could have had — enough

information to determine that trouble was ahead. Somehow it was obscured by fog. How can we get better

at seeing through the fog?

Why Scope Expands: I

Why Scope Expands: I- Scope creep is depressingly familiar. Its anti-partner, spontaneous and stealthy scope contraction,

has no accepted name, and is rarely seen. Why?

Unresponsive Suppliers: II

Unresponsive Suppliers: II- When a project depends on external suppliers for some tasks and materials, supplier performance can

affect our ability to meet deadlines. How can communication help us get what we need from unresponsive

suppliers?

The Risk of Astonishing Success

The Risk of Astonishing Success- When we experience success, we're more likely to develop overconfidence. And when the success is so

extreme as to induce astonishment, we become even more vulnerable to overconfidence. It's a real risk

of success that must be managed.

Allocating Action Items

Allocating Action Items- From time to time in meetings we discover tasks that need doing. We call them "action items."

And we use our list of open action items as a guide for tracking the work of the group. How we decide

who gets what action item can sometimes affect our success.

See also Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!