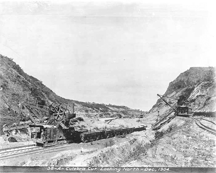

An excavator loads spoil into rail cars in the Culebra Cut, Panama, 1904.

Photo courtesy Wikipedia.

Some projects get into real trouble — real trouble, not just a speedbump. When that happens, we attribute the trouble to the usual suspects — misconceived plans, poor leadership, insufficient resources, and so on. But one suspect that's often ignored is team culture. Culture can limit how a team responds to trouble at any stage of the unfolding catastrophe. And sadly, even when we make risk plans, we rarely plan for the risks associated with the idiosyncrasies of team culture.

In a series of research papers, books, articles, and Web sites, over a period of five or six decades and still counting, Geert Hofstede developed, tuned, and applied a model of cultures that has predictive value for nations, for businesses large and small, and, as I'm suggesting here, for project teams as they respond to trouble. Hofstede's model, based on his cultural dimensions theory, describes cultures in terms of six dimensions: Power Distance, Individualism/Collectivism, Uncertainty Avoidance, Masculinity/Femininity, Long/Short Term Orientation, and Indulgence/Restraint. Of these, three are most relevant for project teams executing high-risk projects: Power Distance, Individualism/Collectivism, and Uncertainty Avoidance.

These cultural A cultural attribute known as

power distance can affect a

team's ability to execute high-

risk projects successfullyattributes suggest the possibility of dramatic differences in a society's — or a company's or a team's — ability to successfully undertake challenging, high-risk projects. I'll address Uncertainty Avoidance and Individualism/Collectivism in future posts. For now, let's examine Hofstede's concept of a culture's Power Distance, and next time discuss how it might affect a team's ability to deal with high-risk projects successfully.

Hofstede defines power distance as "the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions…accept and expect that power is distributed unequally." [Hofstede 2011] To measure the Power Distance of a culture, Hofstede developed an index or scale, as defined by the perceptions of the society's members with least power. But for purposes of this exploration, it's sufficient to compare Large Power Distance (Large-PD) teams to Small Power Distance (Small-PD) teams in terms of the way they deal with unequally distributed power.

Below is a selection of attributes of Large-PD and Small-PD teams. It follows a similar list of Hofstede's that applies to societies. I've rephrased the items somewhat to apply to teams and the organizations that charter them.

| Small Power Distance | Large Power Distance |

|---|---|

The legitimacy of the use of power is subject to moral standards — good or evil, right or wrong, ethical or unethical | Power inequality is a fact of life and the legitimacy of its use isn't a consideration |

Power holders treat subordinates almost as equals; power holders and subordinates regard themselves as collaborators | Subordinates are expected to obey — and they expect themselves to obey — the commands and directions of power holders |

Hierarchy is present only when necessary, and then, minimally | Hierarchy is an unquestioned fact of life |

Training is learner-centered, and professional development is a primary goal | Training is employer-centered and timed and designed to meet the needs of the employer |

Subordinates expect to be consulted and expect to have a say in the work they do and the direction of the team | Subordinates expect to be told what to do |

Management's approach is collaborative; managers view themselves as servant leaders | Management is autocratic, and based on co-optation of the efforts and creativity of subordinates |

Management changes are driven by performance, merit, and expertise required by the project | Management is changed by top-down reorganizations, re-assignments, and by mergers or hostile takeovers |

Corruption is rare; scandals lead to disciplinary action, including termination | Corruption is common; scandals are covered up |

Compensation distribution is relatively even, with variations driven by market forces | Compensation distribution is very uneven and is biased in favor of power holders over their subordinates |

There is relatively little concern for status or status symbols; power level confers very little privilege in terms of amenities; material resource allocations are determined by the nature of the work | There is relatively great concern for status and status symbols; office size and numbers of windows matter; there is segregation by power level for dining, office location, parking, and accommodations while traveling |

An intriguing question presents itself: To what extent do these cultural differences with respect to Power Distance affect the success of high-risk projects? An example might provide helpful motivation.

Between 1881 and 1894, Ferdinand de Lesseps, with French backing, undertook one of the more significant attempts to construct a canal in Panama. Having had such great success with his sea-level canal at Suez, de Lesseps was the obvious choice for this project. His concept for Panama was similar to that of Suez — a sea-level canal through the Isthmus of Panama. Though his concept was similar, the climate and terrain were not. Suez is relatively flat and a desert; the Isthmus of Panama is mountainous and rain-drenched.

De Lesseps' effort in Panama ended in failure, bankruptcy, and scandal.

In 1904, after resolving the political issues involving Panama and its sovereignty — by what some say were questionable means — the United States purchased from France for $40 million the construction equipment and progress to date. Under John Findley Wallace, the former chief engineer of the Illinois Central Railroad, work resumed along largely the lines laid out by de Lesseps — a sea-level canal through the mountainous isthmus. When Wallace resigned suddenly in 1905, John Frank Stevens, who had built the Great Northern Railway, running from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Seattle, Washington, replaced him. Stevens' experience with that effort seemed relevant to the Panama problem, as the route of the Great Northern Railway traversed the Rocky Mountains.

Stevens quickly made changes to both the canal construction process and the infrastructure, which dramatically improved operational effectiveness. Meanwhile, a U.S. design review of the project in 1905 approved the sea-level canal concept of de Lesseps, thereby committing the United States to the design as it then stood.

But by that point, Stevens had experienced the rains that drench the Isthmus every year. He regarded a sea level cut as unworkable because of the enormous volume of the water from those rains. He conceived a new approach that would manage the runoff most effectively, and which would dramatically reduce the amount of rock and earth to be moved. His approach used locks to raise and lower vessels in their traverse over the mountains, and in 1906, he presented his new design to President Roosevelt, who approved it.

Such radical re-thinking of high-risk projects is not uncommon. Because re-thinking often requires questioning the decisions of powerful people, it's reasonable to suppose that Small-PD organizational cultures are better able to re-think their projects when necessary; and the people working on those projects are more likely to take the risk of pointing out the need to re-think when the need arises. Indeed, Hofstede's research suggests that French culture is Large-PD, while the United States culture is Small-PD. Stevens might have been helped — and de Lesseps might have been hindered — by the power distances of their respective cultures.

Next time, we'll examine several mechanisms by which power distance can affect an organization's re-thinking processes. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Backtracking in Incremental Problem Solving

Backtracking in Incremental Problem Solving- Incremental problem solving is fashionable these days. Whether called evolutionary, incremental, or

iterative, the approach entails unique risks. Managing those risks sometimes requires counterintuitive action.

The Politics of Lessons Learned

The Politics of Lessons Learned- Many organizations gather lessons learned — or at least, they believe they do. Mastering the political

subtleties of lessons learned efforts enhances results.

Project Improvisation and Risk Management

Project Improvisation and Risk Management- When reality trips up our project plans, we improvise or we replan. When we do, we create new risks

and render our old risk plans obsolete. Here are some suggestions for managing risks when we improvise.

On the Risk of Undetected Issues: II

On the Risk of Undetected Issues: II- When things go wrong and remain undetected, trouble looms. We continue our efforts, increasing investment

on a path that possibly leads nowhere. Worse, time — that irreplaceable asset — passes.

How can we improve our ability to detect undetected issues?

Seven Planning Pitfalls: I

Seven Planning Pitfalls: I- Whether in war or in projects, plans rarely work out as, umm well, as planned. In part, this is due

to our limited ability to foretell the future, or to know what we don't know. But some of the problem

arises from the way we think. And if we understand this we can make better plans.

See also Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!