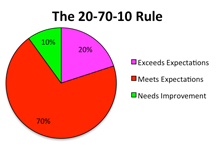

The 20-70-10 rule, graphically. The main problem with this scheme for appraising performance is that it doesn't actually appraise performance. It does categorize people, but that isn't what the enterprise really needs. The enterprise needs performance appraisal — of the enterprise.

We continue with our exploration of some of the foundational misconceptions underlying performance appraisal as it's widely practiced. last time we sketched how a rhetorical fallacy known as the fallacy of composition, which lies at the heart of performance appraisal strategy, prevents performance management systems from attaining their stated goals. We also examined the reification error, and what I called the "myth of identifiable contributions" and the "myth of omniscient supervision."

Let's now take a look at the effects of uniform quotas. In some organizations, as part of the annual review process, supervisors receive quotas for each grade of performance appraisal — a so-called "vitality curve." For example, one quota system, known as the 20-70-10 rule, recommends quotas of 20% for Exceeds Expectations, 70% for Meets Expectations, and 10% for Needs Improvement. When a rule such as this is applied uniformly to all organizational units, madness results.

The problems with uniform quotas are many. Here are just four of them.

- The heterogeneity of capability

- Typically, there is little uniformity of capability across all organizational units. Most units have a mix of people performing at various levels, but some units consist almost exclusively of top performers, while others consist almost exclusively of mediocre performers. The system of uniform quotas compels a supervisor of mostly top performers to rate 10% of his or her supervisees as "Needs Improvement." And the system also compels a supervisor of mostly mediocre performers to rate 20% of them as "Exceeds Expectations."

- Because of the quota, someone who is a top performer relative to the entire organization might be rated as "Needs Improvement" relative to the group of which he or she is a member. And a performer who is actually in the "Meets Expectations" group relative to the entire organization might be rated as "Exceeds Expectations" relative to the group of which he or she is a member.

- Consequently, in some cases, relative to the organization as a whole, a top performer might be rated lower than a mediocre performer. The obvious injustice of this result can contribute to cynicism, toxic conflict, and elevated voluntary termination rates.

- The heterogeneity of the need for capability

- Most enterprises don't need top performers in every role. To recruit and retain top performers when they aren't needed constitutes a waste of enterprise resources. Moreover, top performers need challenges and opportunities to demonstrate creativity. In some roles in some organizations, those desires are positively unhelpful. In some roles, the enterprise needs only reliable, routine levels of performance.

- Despite this, uniform application of the 20-70-10 rule, for example, assumes implicitly that it is desirable to have 20% of the people in each and every unit assessed as top performers. For many roles, this assumption is in contradiction to enterprise needs.

- Serial attrition of talent

- Some units perform work for which there is only a limited pool of capable potential hires. Because of the quota system, when the organization mis-appraises top performers as "Meets Expectations," or worse, those affected might voluntarily terminate if they believe they are being treated unfairly. They do so because the elevated demand for people with their skills means they can readily find alternative employment.

- In this way, uniform quotas applied year after year eventually deplete any units that depend on people with rare and marketable skills and talent.

- A zero-sum game

- Finally, quota systems tend to create environments favorable to demoralization and inter-employee conflict, mainly because they create a zero-sum game. A zero-sum game is a mathematical construct that describes group processes in which the group members are pitted against each other. The total of gains of value summed across all participants is always equal to the total of losses of value summed across them.

- For example, if you're working in a group in which you have a clear sense of who the favored 20% are, and you know you won't be among them, why would you go to great lengths to deliver excellent performance? Indeed, why would you even stay in that position? And inversely, if you were certain that you were among the favored 20%, why would you deliver excellent performance? After all, you know that your supervisor needs to report not less than 20% of his or her supervisees as Exceeds Expectations. Moreover, if you aren't among the favored 20%, and if you try to gain a place among the favored 20%, and they learn of your intentions, they might be motivated to try to prevent you from succeeding. The whole mess is just a nightmare for teamwork.

These phenomena can lead to exits by the most capable people, because they're the people who are most likely able and motivated to find alternative employment. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Critical Thinking at Work:

Paths

Paths- Most of us follow paths through our careers, or through life. We get nervous when we're off the path.

We feel better when we're doing what everyone else is doing. But is that sensible?

Snares at Work

Snares at Work- Stuck in uncomfortable situations, we tend to think of ourselves as trapped. But sometimes it is our

own actions that keep us stuck. Understanding how these traps work is the first step to learning how

to deal with them.

The Halo Effect

The Halo Effect- The Halo Effect is a cognitive bias that causes our evaluation of people, concepts, or objects to be

influenced by our perceptions of one attribute of those people, concepts, or objects. It can lead us

to make significant errors of judgment.

Missing the Obvious: I

Missing the Obvious: I- At times, when the unexpected occurs, we recognize with hindsight that the unexpected could have been

expected. How do we miss the obvious? What's happening when we do?

Hidden Missions

Hidden Missions- When you meet people who seem unfit for their jobs, think carefully before asking yourself why they

aren't replaced immediately. It's possible that they're in place because they're fulfilling hidden missions.

See also Critical Thinking at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!