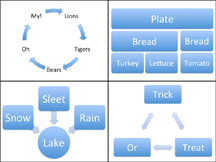

Examples of nonlinear relationships among concepts. Bulleted lists cannot serve to present all kinds of relationships. Sometimes we need alternatives.

In many contexts in organizations, decision makers seek briefings from subject matter experts who are often subordinates or external consultants. These experts then present elements of a "business case" (for or against) some position relative to the issue at hand. And the preferred format for these cases is a series of bullet points. Often, it's a series of series, called a "presentation" or "slide deck." No matter how complex the argument of the business case, bullet points are the preferred form. This fixation on a single form for all arguments is bullet point madness, because it creates a risk of making poor decisions.

In support of this assertion, consider two possible risks. First, the bullet point form might be inherently limited with respect to the kinds of arguments it can represent with clarity. And second, the authors of bullet points might exploit any of the many available tools that can distort the audience's ability to assess the validity of the arguments presented. I'll address this second risk next time. For now, let's consider the inherent limitations of the bullet point format for making complex logical arguments.

The best any presentation can do is to convey an impression that's a simplified but serviceable representation of reality. Presenters and audience alike hope that the simplified forms correspond well enough to reality to ensure the workability of any decisions based on that representation. But the requirement that we must distill all arguments into bullet points, or a series of series of bullet points, limits the set of realities that we can represent accurately enough and completely enough. That leads to trouble, because the bullet point form isn't capable of presenting faithful representations of every reality or every logical argument. And the root of the problem lies in the nature of the bullet point itself.

Experts tell The requirement that we must

distill all arguments into bullet

points, or a series of series of

bullet points, limits the set

of realities that we can

represent accurately enough

and completely enoughus that each bullet point must be concise, crisp, and restricted to a single salient idea. When we write our bullet points, we necessarily trim them down to conform to this ideal. Then, when we actually make the presentation, we restore the connections and supporting ideas that coalesce the bullet points into a coherent whole. When we do that, we try to convey the thought process that the bullet points represent. And therein lies the risk. We have difficulty tying together the bullet points because of a cognitive bias known as the illusion of transparency.

The illusion of transparency is the human tendency to attribute to others greater awareness of our own mental or emotional state than those others actually possess. Common examples of this effect relate to our emotions or our feelings about our own performance. For example, if we feel unsure about our public speaking skills, we tend to believe that the inadequacy we feel is more evident to others than it actually is.

But the illusion of transparency is more powerful than that. It can also affect our assessment of the level of understanding others have of what we're trying to communicate to them. We tend to overestimate how well aligned is the audience's understanding to the message we're trying to convey. And so, when we explain our bullet points — an activity necessitated by our having trimmed them down to their ideal level of crisp conciseness — we tend to overestimate the firmness of the audience's grasp of our complete message.

This overestimate of the audience's understanding arises from our inability to know what audience members are thinking about what we're presenting. We cannot know everything about their background or experience. We cannot know what meaning they're making of our bullet points or our words. We cannot even know how closely they're paying attention, unless something really unusual happens.

A second area of difficulty for the bullet point format is its inherently linear structure. The bullet points in each cluster of bullet points are arranged in some order. When people read them, or listen to them as they're presented, they take them in order, as if one leads logically to the next, or as if one depends logically on its predecessor. In many actual situations, there is no ordering among the bullet points. In other situations, there is an ordering, but the ordering isn't linear. Or there might be a linear ordering for some of the bullets, but the remaining bullets might affect each other mutually, in a loop, or even a web.

Makers of presentation software have provided templates for some of these situations. These templates, some of which are illustrated above, do help when the bullets in question are "near" each other in the thread of the logical argument, and near each other in their physical placement in documents. But some arguments truly do require sprawling webs of relationships among concepts.

Consider, for example, moving an entire information management system from on-premises configurations to the cloud. Hard work is involved, for both presenter and audience. A linear series of bullet points probably wouldn't be able to fairly present the business case for such a complex decision. Most likely, a sound decision would depend on an examination of the issues involved based on something more complex than a series (or series of series) of bullet points.

The bullet point format does have its place — for simple decisions, or for smaller, self-contained sectors of the knowledge space supporting more complex decisions. But that role is limited. For complex decisions, we actually do need to think.

Next time we'll examine some of the tools advocates can use to make the bullet point format appear to provide a stronger foundation for complex decisions than it actually can provide. ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Cognitive Biases at Work:

Effects of Shared Information Bias: I

Effects of Shared Information Bias: I- Shared information bias is the tendency for group discussions to emphasize what everyone already knows.

It's widely believed to lead to bad decisions. But it can do much more damage than that.

The Trap of Beautiful Language

The Trap of Beautiful Language- As we assess the validity of others' statements, we risk making a characteristically human error —

we confuse the beauty of their language with the reliability of its meaning. We're easily thrown off

by alliteration, anaphora, epistrophe, and chiasmus.

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II

Seven Planning Pitfalls: II- Plans are well known for working out differently from what we intended. Sometimes, the unintended outcome

is due to external factors over which the planning team has little control. Two examples are priming

effects and widely held but inapplicable beliefs.

Some Perils of Reverse Scheduling

Some Perils of Reverse Scheduling- Especially when time is tight, project sponsors sometimes ask their project managers to produce "reverse

schedules." They want to know what would have to be done by when to complete their projects "on

time." It's a risky process that produces aggressive schedules.

The Risk of Astonishing Success

The Risk of Astonishing Success- When we experience success, we're more likely to develop overconfidence. And when the success is so

extreme as to induce astonishment, we become even more vulnerable to overconfidence. It's a real risk

of success that must be managed.

See also Cognitive Biases at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!