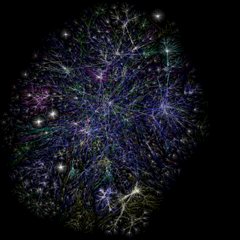

A map of the Internet ca. January 2005. Each line segment connects a pair of nodes. Learning something by accident on the way to learning something on purpose is a common experience of users of the World Wide Web, which resides on the Internet. In my view, though I certainly have no data, the Internet is likely the world's most complex support device for unintentional learning. The Web, Email, Twitter, Facebook and many other Internet-based media provide opportunities for unintentional learning. Exploiting the Internet's capability for supporting intentionally unintentional learning might someday be a well-developed and widely adopted human skill, no doubt supported by applications based on the Internet. Image courtesy OPTE.org.

We usually associate learning with the young, the naïve, or newbies. As sophisticated adults or professionals, we tend to regard ourselves more as having learned rather than as learning. The truth, of course, is that maintaining sophistication or professionalism requires continuous, lifelong learning, including learning about learning itself.

Intentional learning entails deciding to learn about something specific. We read about diseases of houseplants to try to determine what's wrong with the schefflera; we practice telling a new joke to improve our delivery; or we take tennis lessons to elevate the strategic part of our game.

In this culture, intentional learning is highly valued. We hold in high esteem achievements such as degrees and certifications, and we grant or lend resources to help those pursuing those degrees and certifications. But while we do value intentional learning, that valuing is most specific, as evidenced by the specificity of the goals of these activities. Degree-granting institutions must themselves be accredited. And the marketing literature of most training programs includes sections titled "What Attendees Learn" or "Learning Objectives" or even "Measurable Outcomes."

Even so, it's likely that most learning is unintentional. We accidentally discover keyboard shortcuts in Outlook; a colleague relates tidbits of market intelligence that explain the CEO's latest announcement; we witness a miscommunication between two colleagues and resolve never to use that particular phrasing again ourselves.

Because unintentional learning is so productive, a natural question arises: What if we intentionally create opportunities for unintentional learning? Intentional learning without specific goals offers several advantages.

- Prerequisites are less restrictive

- Since the goals are nonspecific, prerequisites for unintentional learning in a given field of knowledge relate more to the will and ability to learn than they do to specific capabilities in that field of knowledge. This enables the learner to explore more broadly than learners who use a more conventional goal-oriented approach.

- The learning is less biased

- The more specific our learning goals are, the less likely we are to acquire knowledge unrelated to those goals. And that unrelated knowledge can be more useful and beneficial than what we set out to learn in the first place. Just as goals provide direction and focus, they also bias the undertaking — that's how they provide focus. And just as there is a place for goal-oriented learning, there is a place for less-goal-oriented learning.

- Spectacularly beneficial discontinuities are more likely

- When we open When we open our minds to intentionally

unintentional learning, sudden, disruptive,

"aha's" become more likelyour minds to intentionally unintentional learning, sudden, disruptive, "aha's" become more likely. And these unexpected insights can be the sources of the spectacularly beneficial discontinuities that lead to life-altering choices in the personal domain, or disruptive innovations in the business domain.

As this day closes, perhaps you'll reflect on what you learned today. Maybe you'll notice some things that you didn't intend to learn when this day began. And tomorrow, maybe there will be even more. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Love the work but not the job? Bad boss, long commute, troubling ethical questions, hateful colleague? This ebook looks at what we can do to get more out of life at work. It helps you get moving again! Read Go For It! Sometimes It's Easier If You Run, filled with tips and techniques for putting zing into your work life. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness:

Some Costs of COTS

Some Costs of COTS- As a way of managing risk, we sometimes steer our organizations towards commercial off-the-shelf (COTS)

components, methodologies, designs, and processes. But to gain a competitive edge, we need creative

differentiation.

Inner Babble

Inner Babble- It goes by various names — self-talk, inner dialog, or internal conversation. Because it is so

often disorganized and illogical, I like to call it inner babble. But whatever you call it,

it's often misleading, distracting, and unhelpful. How can you recognize inner babble?

Guidelines for Delegation

Guidelines for Delegation- Mastering the art of delegation can increase your productivity, and help to develop the skills of the

people you lead or manage. And it makes them better delegators, too. Here are some guidelines for delegation.

False Summits: II

False Summits: II- When climbers encounter "false summits," hope of an early end to the climb comes to an end.

The psychological effects can threaten the morale and even the safety of the climbing party. So it is

in project work.

Symbolic Self-Completion and Projects

Symbolic Self-Completion and Projects- The theory of symbolic self-completion holds that to define themselves, humans sometimes assert indicators

of achievement that either they do not have, or that do not mean what they seem to mean. This behavior

has consequences for managing project-oriented organizations.

See also Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!