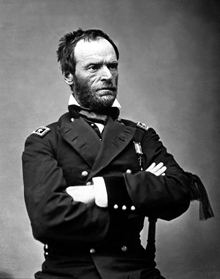

William Tecumseh Sherman as a major general in May 1865. The black ribbon of mourning on his left arm is for President Lincoln. General Sherman is famous for having said, upon learning that there were those who wanted to nonimate him for the office of President in the election of 1864, "I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected." Such unambiguous statements are so rare in U.S. politics that they are now called Shermanesque statements. Apparently, it was necessary to be so unambiguous, even in 1864, because the population in general, and the press in particular, had grown so accustomed to carefully parsing the statements of public figures. For Gen. Sherman to decline any less explicitly probably would not have been effective.

We rarely need Shermanesque statements at work, but humor can be a useful tool in achieving the required level of clarity. Portrait by Mathew Brady, available at Wikipedia.

Some people write email badly. It's unclear, ambiguous, or just hard to understand. When they speak on the phone, or in person, what they say seems less opaque, because if something isn't clear, you can ask a question, and you get a clarifying answer. No, these people seem to be unclear only in email.

Among those who fairly consistently write unintelligible email messages are those who don't know the language well. They aren't the subjects of this article. Let's consider only those who know the language and who consistently author unintelligible email messages. What's going on?

To understand why these people produce unintelligible email messages, begin by appreciating the advantages ambiguity and opacity offer to senders of such messages.

- Insulation from commitment

- By avoiding commitment to clear positions, the authors of unclear email messages leave themselves room to maneuver. If one possible interpretation proves wrong or politically undesirable, the author can say, "No, I didn't mean that, I meant this."

- Insulation from responsibility

- Consider, for example, ambiguous or unclear messages that supposedly contain directions or orders. If the directions are unclear, the author can claim that the recipient misinterpreted them if trouble develops. If the order is unclear, and trouble develops, the giver of the order can claim that the action taken was not the action that was ordered. Ambiguity shelters the author from responsibility.

- Ambiguity saves time

- Writing withBy avoiding commitment to clear

positions, the authors of unclear

email messages leave themselves

room to maneuver clarity is difficult. Authors must consider possible misinterpretations of what they write, and devise language that limits the interpretations to those the author intends. Ambiguity is much easier to achieve. - Intimidation offers additional protection

- If recipients request clarification, the author can intimidate them: "What part of X don't you understand?" Or, "I thought the message was perfectly clear, but apparently, not for someone like you." Or, "You missed your calling. You should have been a lawyer." (Ineffective for recipients who are lawyers)

The effect on recipients can be maddening. They often know that seeking clarification is risky, but choosing an interpretation that might be wrong is even riskier. They huddle among themselves, working out scenarios and hoping they'll discover the right interpretation, or maybe one that's less risky than the others. They dare not seek telephonic clarification, because they need evidence justifying the choice they ultimately make. A phoned request for clarification doesn't help.

There is a tactic that sometimes works. Recipients can send the author of the ambiguous message an email message that reads, in essence, "OK, got it. We'll do X, exactly as you suggest in your message below." The author of the ambiguous message then has a choice: (a) approve the interpretation; (b) correct it, again ambiguously; or (c) deny receiving the message. If the sender chooses (a), and X is unambiguous, the recipient has the clarification sought. If the sender chooses (b), the recipient can repeat the tactic. After a pattern of responses of type (c) is established, they lose credibility.

Posting this article where all can see it can help, too. Everyone will know who this article is about. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Effective Communication at Work:

When Naming Hurts

When Naming Hurts- One of our great strengths as Humans is our ability to name things. Naming empowers us by helping us

think about and communicate complex ideas. But naming has a dark side, too. We use naming to oversimplify,

to denigrate, to disempower, and even to dehumanize. When we abuse this tool, we hurt our companies,

our colleagues, and ourselves.

Begging the Question

Begging the Question- Begging the question is a common, usually undetected, rhetorical fallacy. It leads to unsupported conclusions

and painful places we just can't live with. What can we do when it happens?

The Fine Art of Quibbling

The Fine Art of Quibbling- We usually think of quibbling as an innocent swan dive into unnecessary detail, like calculating shares

of a lunch check to the nearest cent. In debate about substantive issues, a detour into quibbling can

be far more threatening — it can indicate much deeper problems.

Masked Messages

Masked Messages- Sometimes what we say to each other isn't what we really mean. We mask the messages, or we form them

into what are usually positive structures, to make them appear to be something less malicious than they

are. Here are some examples of masked messages.

On Facilitation Suggestions from Meeting Participants

On Facilitation Suggestions from Meeting Participants- Team leaders often facilitate their own meetings, and although there are problems associated with that

dual role, it's so familiar that it works well enough, most of the time. Less widely understood are

the problems that arise when other meeting participants make facilitation suggestions.

See also Effective Communication at Work for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!