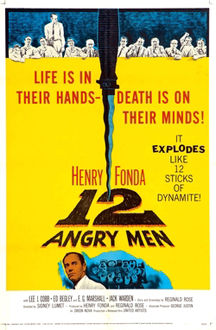

Promotional poster for the 1957 film Twelve Angry Men. The jury retires to deliberate, and right away it's 11-1 to convict, but one dissenter gradually brings the rest around. Watch it for the drama, or watch it to learn something about groupthink, leadership, team conflict, influence, and team dynamics. Director: Sidney Lumet. Lee J. Cobb, Henry Fonda, and many more greats. 1957. DVD: 96 min. Order from Amazon. Image courtesy Wikimedia.

To influence is to have an effect on people that helps to determine their actions, behavior, perceptions, or attitudes. The opposite of influence is to have no effect. But most of us regard influencing others as bringing their actions, behavior, and views more into line with our own. The opposite of that sense of influence would then be inducing others to adopt positions that contradict our own.

Because I know of no English word for that kind of influence, I'll call it anti-influence. Like influence, anti-influence can be abused, but let us consider only unintentional anti-influence.

Especially in knowledge-oriented workplaces, anti-influence can be costly, when groups engaged in collaborative problem solving might reject contributions that could have led to brilliant solutions. How does this happen?

One widely used framework for studying influence consists of six principles of persuasion developed by Robert Cialdini. For each of the six, I suggest below how they can lead to anti-influence.

- Reciprocity

- To use reciprocity, the influencer induces in the target a sense of indebtedness by means of gifts or favors.

- If someone frequently fails to reciprocate, others may develop resentments. Then later, when the nonreciprocator tries to influence the team, suspicion and resentment can block adoption of any of the nonreciprocator's suggestions.

- Commitment and consistency

- People like to see themselves as consistent — that they follow through on their commitments.

- If an Especially in knowledge-

oriented workplaces,

anti-influence can be costlyanti-influencer is known for inconsistency, and not following through, others might develop distrust. The probability of rejection of his or her contributions is then elevated, however obviously correct they might be. - Social proof

- When we're uncertain, we seek confirmation of our choices by observing what others do.

- Most companies, departments, and work groups loathe being the first to adopt a practice. And if someone who's widely disrespected advocates a position, that disrespect affects how people assess the advocated position, likely due, in part, to the halo effect.

- Liking

- People we like, especially people who are like us, or whom we find physically attractive, are more effective influencers — for us.

- If someone is widely disliked, when that person tries to influence the team to adopt a position, that dislike affects how people assess the advocated position, likely due again, in part, to the halo effect.

- Authority

- People respect authority. At work, the emblems of authority are rank and professional respect, often indicated by office location, size, and furnishings.

- People of low rank, or who are new to the organization or to the subject matter, or who lack elite professional credentials, have a more difficult time gaining adherents to their positions, however correct they may be.

- Scarcity

- The principle of scarcity is that the more rare and difficult-to-obtain something is, the more it's valued.

- Those who offer their opinions and thoughts too liberally are more likely to find them ignored or even opposed.

Watch for behaviors that might confer anti-influencer status. Once you identify anti-influencers, you're better able to assess their contributions objectively. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Workplace Politics:

The High Cost of Low Trust: II

The High Cost of Low Trust: II- Truly paying attention to Trust at work is rare, in part, because we don't fully appreciate what distrust

really costs. Here's Part II of a little catalog of how we cope with distrust, and how we pay for it.

How to Avoid a Layoff: Your Situation

How to Avoid a Layoff: Your Situation- These are troubled economic times. Layoffs are becoming increasingly common. Here are some tips for

positioning yourself in the organization to reduce the chances that you will be laid off.

How to Undermine Your Boss

How to Undermine Your Boss- Ever since I wrote "How to Undermine Your Subordinates," I've received scads of requests for

"How to Undermine Your Boss." Must be a lot of unhappy subordinates out there. Well, this

one's for you.

Ground Level Sources of Scope Creep

Ground Level Sources of Scope Creep- We usually think of scope creep as having been induced by managerial decisions. And most often, it probably

is. But most project team members — and others as well — can contribute to the problem.

Not Really Part of the Team: I

Not Really Part of the Team: I- Some team members hang back. They show little initiative and have little social contact with other team

members. How does this come about?

See also Workplace Politics for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!