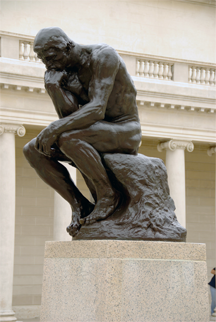

"The Thinker," a bronze sculpture by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). Thinking can be helpful when we encounter difficulty resolving issues in debates. The explanations we devise to help us understand why others disagree with us are results of thinking that is often mistaken if focus on our debate opponents' shortcomings. A more useful application of thinking might be a focus on our own positions, or better, on our own shortcomings.

This photo, by Karora, is of the statue at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, courtesy Wikimedia.

When we debate substantive issues with others at work, and progress towards resolution stalls, we sometimes suspend open debate. Meanwhile, though, the debate can continue in our minds, or privately among like-minded colleagues. One focus of ongoing private debate is a series of attempts to explain why those on the other side disagree. Ironically, many of the more popular explanations perhaps tell us more about ourselves than they do about the behavior or obstinacy of those with whom we disagree.

In what follows, I'll refer in the first person to those offering explanations — "us," "our," and "we." I'll refer in the third person to "our" debate opponents — "they," "their," and "them."

- They're being illogical

- Do we really believe that their capacity for logical reasoning is insufficient for this particular task? Really?

- What appears as a logical flaw in their thinking can actually arise from information we ourselves lack or have forgotten. Or possibly, someone else is actively concealing that information. When logical errors seem like the best explanation, search instead for forgetfulness, deception, self-deception, hidden agendas, or blind agendas.

- They're being hypocritical or inconsistent

- When it seems that they're applying a standard inconsistently, especially for their own benefit, hypocrisy is a possibility. But do they really think so little of our powers of perception that they believe we won't notice?

- Explanations of others' behavior by which we place ourselves in morally superior positions deserve close scrutiny. Examine carefully the argument that they're being inconsistent. Is all the evidence available and valid? Is there no other interpretation of that evidence?

- Our arguments are weak

- Perhaps they disagree because our arguments are weak or flawed in some way. An indicator of this explanation is the urge to perfect one's arguments and try again.

- If we've Explanations of others' behavior

by which we place ourselves in

morally superior positions

deserve close scrutinybeen careful, our arguments are probably correct. A more likely possibility is that we haven't evaluated our arguments from our debate opponents' perspective, which can include false assumptions or outdated or incorrect information. Check that the arguments address such matters effectively. - Our arguments are sound, but they don't understand

- Perhaps they just can't follow our arguments. Really? Are they so challenged mentally?

- This is another explanation that is as dubious as it is self-serving. If they're unable to follow the thread of our arguments, perhaps the problem is that we're expressing them poorly. Even worse, perhaps our approach is condescending or offensive in some other way. If what we say moves them to anger, it is our own actions that may be compromising their ability to think clearly.

Finally, when we suggest that our failure to resolve the issues in question is evidence of our opponents' corruption, we're adopting a very risky position. If we're mistaken, we've placed in jeopardy our relationship with our debate opponents. Damage can be permanent. If we're correct, then we have a problem more severe than our inability to resolve the question at hand. Attend to that instead. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are you fed up with tense, explosive meetings? Are you or a colleague the target of a bully? Destructive conflict can ruin organizations. But if we believe that all conflict is destructive, and that we can somehow eliminate conflict, or that conflict is an enemy of productivity, then we're in conflict with Conflict itself. Read 101 Tips for Managing Conflict to learn how to make peace with conflict and make it an organizational asset. Order Now!

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Conflict Management:

The Advantages of Political Attack: III

The Advantages of Political Attack: III- In workplace politics, attackers have significant advantages that explain, in part, their surprising

success rate. In this third part of our series on political attacks, we examine the psychological advantages

of attackers.

On Snitching at Work: I

On Snitching at Work: I- Some people have difficulty determining the propriety of reporting violations to authorities at work.

Proper or not, reporting violations can be simultaneously both risky and necessary.

Covert Verbal Abuse at Work

Covert Verbal Abuse at Work- Verbal abuse at work uses written or spoken language to disparage, disadvantage, or harm others. Perpetrators

favor tactics they can subsequently deny having used. Even more favored are abusive tactics that are

so subtle that others don't notice them.

Fear/Anxiety Bias: II

Fear/Anxiety Bias: II- When people sense that reporting the true status of the work underway could be career-dangerous, some

shade or "spin" their reports. Managers then receive an inaccurate impression of the state

of the organization. Here are five of the patterns people use.

When Retrospectives Turn into Blamefests: III

When Retrospectives Turn into Blamefests: III- Although retrospectives do foster organizational learning, they come with a risk of degeneration into

blame and retaliation. One source of this risk is how we responded to issues uncovered in prior retrospectives.

See also Conflict Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!