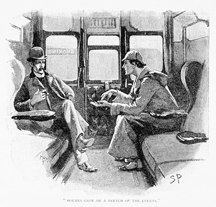

Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson, in an illustration by Sidney Paget, captioned "Holmes gave me a sketch of the events." The illustration was originally published in 1892 in The Strand magazine to accompany a story called The Adventure of Silver Blaze by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It is in this story that the following dialog occurs:

Gregory (Scotland Yard detective): "Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?"

Holmes: "To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time."

Gregory: "The dog did nothing in the night-time."

Holmes: "That was the curious incident."

From this, Holmes deduces that the dog's master was the villain. This is an example of Holmes' overcoming a cognitive bias I refer to here as absence blindness.

Original book illustration, courtesy Wikimedia.

Some organizations seem to be constitutionally averse to planning for complex projects. They do sometimes plan simple projects, informally, but for projects sufficiently large or complex, they don't plan well at all. Their plans are generally shoddy and ineffective; when they do produce plans, their people lack the patience to execute those plans effectively; and people who actively advocate for planning find themselves cast as disloyal empire-builders. Worse, those who advocate for risk planning are cast as cynical pessimists. Periodically, these planning-averse organizations must confront their addiction to brashness, usually after an exceptionally disappointing and stressful project experience. Haphazard attempts to plan do follow, but no plan survives for long before the next shortsighted, haphazard plan displaces it.

These are the observable characteristics of the planning dysfunction cycle. How does it arise? What sustains it?

To answer questions like these about systems involving people, it's useful to separate investigations of the origin of the situation from investigations of its sustenance, because the two dynamics can be so different. So let me focus for now on the question of sustenance. Given the trail of disappointing results, what keeps the cycle going? Why do these organizations fail to adopt more sensible and effective approaches to planning?

What follows are conjectures about planning deficiencies for large, complex projects. For those projects, planning well is necessary for success. And for those projects, planning well is truly difficult. Four phenomena provide energy for the planning dysfunction cycle.

- Planning and doing are in tension

- Because planning requires effort and takes time, planning and doing are in tension with each other. Planning defers doing. Planning consumes resources that doing requires. Whatever might be happening, whatever the situation, planning delays action. The urge to "get on with it" can be overwhelming. Whether the sense of urgency arises from fear of calamity or from a desire to exploit a rare opportunity, resisting a call to action can be far more difficult than resisting a call to plan.

- Succumbing prematurely to the call to action ensures the incompleteness of the plan, and elevates the probability of failure.

- We incur the costs of planning now, but we receive its benefits later

- The difference between the arrival time of the cost of planning and the arrival time of the benefits of planning creates a challenge for advocates of planning. That challenge is related to hyperbolic discounting, a cognitive bias affecting decisions about choices between items that arrive at different times.

- Humans value items according to their arrival times. An item arriving in the near future is worth more than an identical item arriving in the more distant future. But the perceived difference in values of these two items favors the early arrival more than is justified by the difference in arrival times. A time-consistent valuation would assign a constant percentage value discount per unit of time delay. That form of discounting is called exponential discounting.

- Many careful experiments have demonstrated that humans inherently use a different discounting pattern known as hyperbolic discounting. [Laibson 1997] In hyperbolic discounting, the value assigned to early-arriving items exceeds what would be assigned by exponential discounting. In the context of deciding how carefully to plan, we therefore tend to overvalue near-term costs compared to long-term benefits. Thus hyperbolic discounting causes us to view planning (incorrectly) as costing more than it is worth.

- The benefits of planning are less evident than its costs

- The benefits of careful planning often appear in the form of troubles that don't arise, disasters that don't happen, or expenses that don't need to be expended. Therefore many of the benefits of planning aren't directly observable. By contrast, the costs of planning in terms of effort and delay are directly observable.

- Even when When we focus only on what's here,

we can fail to notice what isn't herewe're in the midst of experiencing the benefits of planning, we tend not to notice them because of a cognitive bias called absence blindness. [Kaufman 2010] Absence blindness is a cognitive bias that causes us to tend not to notice what isn't there, or what doesn't happen, even if the item we don't notice is usually present or usually occurs. When a project runs smoothly, absence blindness causes us not to notice that troubles aren't occurring. Because the benefits of planning are less evident than are its costs, we tend to overvalue planning costs compared to planning benefits. - All plans are imperfect

- However carefully we plan complex projects, we can't anticipate everything that can go wrong, and our knowledge of what needs to be accomplished is probably incomplete. Inevitably, we find imperfections in our plans. We need to backtrack to redo some things, and we eventually realize that other things we did were unnecessary.

- People who oppose the advocates of planning see these imperfections in plans as evidence of the rightness of their position. Moreover, because of a cognitive bias called confirmation bias, they seek out these incidents. When they find them, they feel that their arguments are validated. They point to the relative absence, by comparison, of benefits of planning. In doing so, they usually fail to recognize that absence blindness and confirmation bias have led them to overlook many planning benefits. Since their comparison of the relative importance of the planning imperfections and hazards avoided is unscientific, their conclusions are invalid, but weighty nevertheless.

These four phenomena combine synergistically to reinforce a view that careful planning is grossly overvalued. That synergy generates comments like these:

- We've done enough planning. We now see clearly enough how the work will go. Let's get started. More planning will cost more money and only delay the work.

- It's true that if we invest in careful planning, we'll probably have a better project experience. But how much better? The improvement won't justify additional planning costs, and it will just delay the effort. The last time we had a pretty decent plan, it turned out to be a waste of effort, because the project went so smoothly, no problems at all. What a waste.

- Don't you remember what happened with the project before that one? We thought we had planned enough. Some of us thought we over-planned. They might have been right, too, because even though we thought we had a good plan, we still had trouble. The return on investment for planning is too low and too unpredictable.

These arguments, bogus though they might be, are powerful indeed. Overcoming the urge to "get on with it" is difficult, but overcoming the urge is easier when we understand how our own thought processes work against us. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Projects never go quite as planned. We expect that, but we don't expect disaster. How can we get better at spotting disaster when there's still time to prevent it? How to Spot a Troubled Project Before the Trouble Starts is filled with tips for executives, senior managers, managers of project managers, and sponsors of projects in project-oriented organizations. It helps readers learn the subtle cues that indicate that a project is at risk for wreckage in time to do something about it. It's an ebook, but it's about 15% larger than "Who Moved My Cheese?" Just . Order Now! .

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Films Not About Project Teams: I

Films Not About Project Teams: I- Here's part one of a list of films and videos about project teams that weren't necessarily meant to

be about project teams. Most are available to borrow from the public library, and all are great fun.

Nine Project Management Fallacies: IV

Nine Project Management Fallacies: IV- Some of what we "know" about managing projects just isn't so. Understanding these last three

of the nine fallacies of project management helps reduce risk and enhances your ability to complete

projects successfully.

The Politics of Lessons Learned

The Politics of Lessons Learned- Many organizations gather lessons learned — or at least, they believe they do. Mastering the political

subtleties of lessons learned efforts enhances results.

Risk Management Risk: II

Risk Management Risk: II- Risk Management Risk is the risk that a particular risk management plan is deficient. Here are some

guidelines for reducing risk management risk arising from risk interactions and change.

Anticipating Absence: Why

Anticipating Absence: Why- Knowledge workers are scientists, engineers, physicians, attorneys, and any other professionals who

"think for a living." When they suddenly become unavailable because of the Coronavirus Pandemic,

substituting someone else to carry on for them can be problematic, because skills and experience are

not enough.

See also Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!