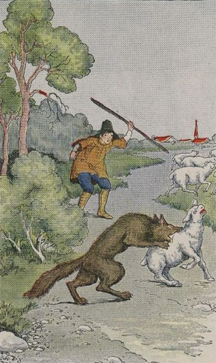

The Boy Who Cried Wolf, illustrated by Milo Winter in a 1919 Aesop anthology. This fable, attributed to Aesop, tells the story of a shepherd boy who repeatedly — and falsely — alerted villagers that a wolf was attacking his flock. He did this as an entertainment. Finally, when a wolf actually did attack his flock, the villagers didn't believe him. He had lost all credibility. In this case, the loss of credibility was due not to any of the behavioral factors described here, but to deliberate disinformation. Disinformation does occur in organizations, but it is much less common than the other factors, and it falls outside the realm of factors that degrade credibility without your actually being wrong. Other similar factors include deceits of various types, baseless accusations, ethical transgressions, and associations with others similarly inclined. Photo courtesy Project Gutenberg.

Whether you want to advance your career, or just keep your job, credibility matters. It's a basis for trust. It determines what assignments come your way. And when things go wrong, credibility can protect you from accusations, real or false.

If you have credibility, it's easy to forget that you do. But after you've lost credibility, you notice its absence almost everywhere you turn.

Sometimes it's easy to understand why you lost credibility. Mistakes, for example, can do it. One or two spectacularly avoidable blunders can pretty much finish you off. But a string of less-than-spectacular errors can erode credibility too, if there are so many of them that they become predictable.

More interesting are the behaviors that erode credibility without your actually being wrong about anything. Here are some attitudes we project that erode credibility.

- Desperation

- Sometimes being believed — about almost anything — becomes so important to us that anxiety and desperation become evident. This can arouse suspicions that being believed is more important than being right. Others believe that we might even lie to ourselves and thus become incapable of knowing the truth.

- Arrogance

- Nobody likes — or more to the point — nobody believes a know-it-all. People generally have difficulty accepting that someone can know it all, perhaps because it reflects on their own limitations. But even if we actually do know it all, others can become determined to demonstrate that there are limits to any one person's knowledge. They can do that through disbelief.

- Nonchalance

- An attitude of disrespect for truth projects a disregard for the difference between truth and fiction. Nonchalance about being mistaken can give others cause to doubt that we care about the truth of what we say.

- Uncertainty

- Uncertainty and confidence are linked to credibility in a paradoxical way. The more uncertain we are, the less credible we are. The more confident, the more credible. This seems only sensible. But paradoxically, the more competent we are, the less confident we seem. The less competent we are, the more confident we seem. Read more about this in "The Paradox of Confidence," Point Lookout for January 7, 2009.

- Ulterior motives

- When others Sometimes being believed

— about almost anything —

becomes so important to us

that anxiety and desperation

become evidentbelieve we have motives other than surfacing Truth, they tend to question our claims even when those claims are true. For example, if we have contempt for some of the people involved in the topic at hand, or if others suspect that we wish them to fail, our questions, skepticism, and words of warning will likely be ineffective, or even anti-effective.

If you think that any of these factors might be limiting your credibility, talking about them with others might help, but it could enhance the risk of appearing desperate, as described above. You have little or no control over what other people believe. Instead, focus on eliminating them from your own behavior. Be the best You that you can be. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Is every other day a tense, anxious, angry misery as you watch people around you, who couldn't even think their way through a game of Jacks, win at workplace politics and steal the credit and glory for just about everyone's best work including yours? Read 303 Secrets of Workplace Politics, filled with tips and techniques for succeeding in workplace politics. More info

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness:

Shooting Ourselves in the Feet

Shooting Ourselves in the Feet- When you give a demo to a small audience, there's a danger of overwhelming them in a behavior I call

"swarming." Here are some tips for terrific demos to small audiences.

Take Any Seat: II

Take Any Seat: II- In meetings, where you sit in the room influences your effectiveness, both in the formal part of the

meeting and in the milling-abouts that occur around breaks. You can take any seat, but if you make your

choice strategically, you can better maintain your autonomy and power.

Team-Building Travails

Team-Building Travails- Team-building is one of the most common forms of team "training." If only it were the most

effective, we'd be in a lot better shape than we are. How can we get more out of the effort we spend

building teams?

How to Make Meetings Worth Attending

How to Make Meetings Worth Attending- Many of us spend seemingly endless hours in meetings that seem dull, ineffective, or even counterproductive.

Here are some insights to keep in mind that might help make meetings more worthwhile — and maybe

even fun.

The Perils of Piecemeal Analysis: Content

The Perils of Piecemeal Analysis: Content- A team member proposes a solution to the latest show-stopping near-disaster. After extended discussion,

the team decides whether or not to pursue the idea. It's a costly approach, because too often it leads

us to reject unnecessarily some perfectly sound proposals, and to accept others we shouldn't have.

See also Personal, Team, and Organizational Effectiveness for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!