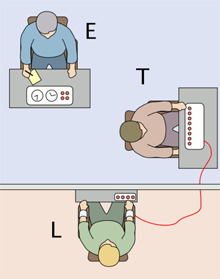

A schematic representation of the Milgram Experi|-ment, which explored the power of the urge to obey authority. In the experiment, devised by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram, and first conducted in the early 1960s, an experimenter (E) instructs a test subject (T) in the training of a learner (L). The experimenter plays the role of an authority figure. The test subject plays the role of a teacher or trainer. The learner is an actor separated from the experimenter and test subject by an opaque screen. In the experiment, T is instructed to apply a series of electric shocks to L whenever L makes a mistake. The shocks escalate in power. In reality, L never receives any shocks at all, but emits a series of auditory responses that escalate from expressions of pain in response to the early, light shocks, all the way to screams of agony and finally death, in response to the most powerful shocks. If T becomes reluctant, E provides a series of verbal prods of escalating urgency. The experiment is intended to determine to what degree it is true that when instructed to do so by an authority figure, humans are almost universally capable of administering pain and harm at any level of severity. Replications of the experiment yield fairly uniform results that have been interpreted to mean that humans do exhibit this capability.

However, given what we now know about the online disinhibition effect, one important question about this result does arise. That question involves the asymmetry of immediacy in the E/T and T/L relationships, which could account for the difference in the ability of E to influence T through in-person commands and the ability of L to influence T through screams of agony heard through the screen. It's possible that a remote E, having to overcome the effect of minimizing authority identified by Suler, might be unable to compete with T's reluctance to continue shocking L. It's also possible that a more immediate connection to L, through video or perhaps a convincing F2F simulation, might cause L's influence over T to dominate over E's. Image (cc) Expiring Frog, courtesy Wikipedia.

As we saw last time, toxic conflict in virtual teams can arise from the nature of the virtual environment, because in the virtual environment, we sometimes engage in behavior that we self-inhibit when we interact face-to-face (F2F). One factor contributing to this phenomenon is that the virtual environment supports only a weakened form of the connection between our personhood and our actions. In his study of online behavior, psychologist John Suler calls this mechanism dissociative anonymity an element of what he calls the online disinhibition effect.

Suler identifies another mechanism that he calls minimizing authority. Briefly, in the virtual environment, differences in personal status are not as evident as they are F2F, which can encourage behavior in the virtual environment that would be rare F2F. A familiar example is the stream of sometimes-disrespectful email messages that CEOs receive from people all through their organizations. Minimizing authority contributes to the online disinhibition effect by suppressing the inhibitions people have about addressing the CEO, and in what manner they address him or her.

Within virtual teams, minimizing authority has analogous consequences. Here are three examples.

- Ineffective facilitation

- An effective facilitator can impose order F2F with presence alone. Sidebars and interruptions are rare. In the virtual environment, especially one that lacks video, facilitators have much more difficulty maintaining order on the basis of presence, because projecting one's presence is difficult. Muting everyone except the recognized contributor does help, but the meeting pays a price for this in terms of spontaneity and the inability to interrupt legitimately, as one might do for a process question.

- Ineffective project leadership

- Although project managers generally lack formal authority over the members of teams they lead, they do have some authority within the project context. They can use that authority, their personal relationships, and their personal presence to craft a microculture that enables team success. But in the virtual environment, the phenomenon of minimizing authority makes this more difficult. Progress suffers.

- Minimizing subordination

- Minimizing authority In the virtual environment, especially

one that lacks video, facilitators

have difficulty maintaining order

on the basis of presencein the virtual environment also affects those with authority, whose perceptions of their own authority are based, in part, on their experiences of others' perceptions of them. In the virtual environment, since the perceptions of others are affected by minimizing authority, those with authority sometimes see themselves as less authoritative. Moreover, when others behave in a manner that in real life would be viewed as challenging to authority, those with authority can experience a feeling of being disrespected. This can be upsetting, leading to misjudgments, miscommunications, and misbehavior on the part of those with authority.

Loss of effective facilitation, loss of effective leadership, and feeling disrespected make the virtual environment vulnerable to toxic conflict. We'll continue this exploration next time. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are you fed up with tense, explosive meetings? Are you or a colleague the target of a bully? Destructive conflict can ruin organizations. But if we believe that all conflict is destructive, and that we can somehow eliminate conflict, or that conflict is an enemy of productivity, then we're in conflict with Conflict itself. Read 101 Tips for Managing Conflict to learn how to make peace with conflict and make it an organizational asset. Order Now!

For more on Suler's work, visit his Web site. For a lighter look at email in particular, see Daniel Goleman's article, "Flame First, Think Later: New Clues to E-Mail Misbehavior," from The New York Times, February 20, 2007.

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Conflict Management:

The Advantages of Political Attack: III

The Advantages of Political Attack: III- In workplace politics, attackers have significant advantages that explain, in part, their surprising

success rate. In this third part of our series on political attacks, we examine the psychological advantages

of attackers.

False Consensus

False Consensus- Most of us believe that our own opinions are widely shared. We overestimate the breadth of consensus

about controversial issues. This is the phenomenon of false consensus. It creates trouble in the workplace,

but that trouble is often avoidable.

Unresponsive Suppliers: III

Unresponsive Suppliers: III- When suppliers have a customer orientation, we can usually depend on them. But government suppliers

are a special case.

Conversation Irritants: II

Conversation Irritants: II- Workplace conversation is difficult enough, because of stress, time pressure, and the complexity of

our discussions. But it's even more vexing when people actually try to be nasty, unclear, and ambiguous.

Here's Part II of a small collection of their techniques.

Overt Verbal Abuse at Work

Overt Verbal Abuse at Work- Verbal abuse in the workplace involves using written or spoken language to disparage, to disadvantage,

or to otherwise harm others. Perpetrators tend to favor tactics that they can subsequently deny having

used to harm anyone.

See also Conflict Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!