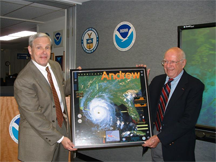

National Weather Service Director Jack Kelly presents civil engineer Herbert Saffir (on right) with a framed poster of Hurricane Andrew depicting the Saffir-Simpson scale for rating the strength of hurricanes. Saffir was co-developer of the scale, with meteorologist Robert Simpson. The phrases, "Category One," "Category Two," and so on, have by now passed into the language, having been applied, informally, to company names, traffic jams, divorces, and more, to name just a few uses.

The categorization scheme might also one day see service for categorizing Storms in task-oriented work groups. One can even imagine a tool for predicting the strength of Storms in projects in advance of their actual arrival.

Image by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, courtesy Wikimedia.

In my two most-recent posts (Dec 25 and Jan 1), I explored how to use Satir's Change Model (SCM) to understand Tuckman's developmental sequence in small groups (TDSSG). [Tuckman 1965] [Tuckman & Jensen 1977] These posts made a tacit assumption of orderly progress — that as a group develops, it moves through the stages of Tuckman's developmental sequence linearly and in order, beginning with the creation of the group. Nor could I find in Tuckman's work an explicit statement that he was or was not making an assumption of orderly progress. But in referring to his stages as a sequence, he does imply that small groups, over the course of their development, traverse the sequence in the order he describes.

Many have observed that this isn't the way things work in practice. Although the groups in the studies Tuckman used in his research probably did follow an ordered, linear development sequence, many groups in practice today cannot. They're subjected to external constraints and forces that compel them to traverse more complex trajectories, though they aren't free to hop around randomly among the Tuckman stages. In this post and the next, I provide six principles that capture the limitations on how groups large and small can move through the stages of Tuckman's model.

The importance of this limitation becomes clear when we consider how and why groups enter and exit the Storming stage.

Six principles of Tuckman stage transitions

At Norming is a challenging process

because the group must work together

to discover how to work togetherthis point the question about Storming has at least the beginnings of an answer. The essence of the question about Storming is this: "Can a group regress to a Storming stage after it has reached Norming or Performing?" The answer is "Possibly." And we can explain how this can happen within a framework of six principles governing stage transitions in TDSSG:

- Forming Events follow every change in group or task. Following a change in group composition, or a change in group structure, or a change in task definition, a Forming event — whether planned or spontaneous — is inevitable. In practical terms, everyone in the group affected by the change must be informed of the change. They must make adjustments, which could require coordination and even collaboration with others.

- Storming is the result of progress in Forming. As word of a change spreads through the group, members make adjustments. Some raise objections, because (a) they prefer the former arrangements, or (b) they've already completed some work that they must now revise or replace, or (c) they cannot accommodate the change for reasons beyond their control. Others seek to exploit the change to advance their own agendas. Some are just confused. Misinformation floats around. These are the main ingredients of the Storming that follows Forming Events. Storming can be chaotic.

- Storming ends when the group reaches consensus about a new or revised set of norms. Until the group reaches a new consensus about how to work together, Storming continues. It gradually abates as the new consensus emerges. The new understanding of the task and the new norms must take into account the recent changes that precipitated this latest Forming Event. If the new norms don't serve that purpose, Storming continues (or resumes).

- To devise or revise norms about working together, a group must enter a Norming stage. This can be a challenging process, because the group must work together to discover how to work together. Adopting norms by open consensus brings the last bits of Storming to an end, enabling work on task to resume (or begin).

- Group consensus about norms is a prerequisite of high performance. Unless the group agrees to a set of norms for working together, debate about norms continues. After reaching consensus about norms, performance accelerates, pausing only occasionally to make minor adjustments revealed by Practice with the new ways of working.

- Upon termination of work on the task, Adjourning takes place. Formal recognition of the termination of work might come in the form of administrative actions alone, such as filing a report or rescinding certain privileges. Celebrations might occur if the work has been successful. If not, grieving occurs, though grieving only rarely receives organizational support. If there are any group events associated with Adjourning, they might include retrospectives, whether or not the work has been successful.

In cases of task cancellation, Adjourning might be initiated during a Storming stage. Although these incidents are complicated, they're rare. A topic for another time.

Storming generally happens because achieving the objectives set in the Forming Event alters — or in some cases disrupts — the structures, relationships, and sense of purpose that served so well in the period before the most-recent Forming Event. For a newly formed group, I call that period Preforming. For an existing group, a change in membership actually creates a new group, while a change in task gives new purpose (or altered purpose) to the work lives of the group's members. Storming follows whenever we engage in Forming-related activities that disrupt the structures and purpose previously established in stages before the most-recent Forming Event.

An example

When we alter the task objectives for a group that has already reached the Performing stage, that group necessarily initiates a Forming Event, because the group needs to orient itself to the new changes. It might even be necessary to distribute some of the new work, or to redistribute some work previously distributed. If group members are added, introductions might be needed. After this Forming Event is completed, the group might enter a Storming stage, perhaps briefly, before it can revise its norms in a Norming stage, and then enter a revised Performing stage.

Examples of Storming stages can be difficult to identify. Storming might be invisible when group members elect to keep their resentments and anger private. Most professionals regard public emotional complaints as "unprofessional," and some cultures actually penalize group members for registering dissatisfaction with the decisions of others. Or Storming might appear to be continuous in task-oriented work groups in which subgrouping has occurred, if Storming in one or more subgroups is misidentified as Storming in the larger group.

Last words

The six principles above are sufficient for representing all transitions a task-oriented work group might make from one stage to another, provided we recognize that a Forming Event (a) isn't a stage and (b) can occur in a variety of forms, such as meetings, email, text messages, or Wikis. These properties of Forming can make Storming appear to be continuous. Next time I'll provide examples of applying these six principles to understand Tuckman stage transitions in specific situations . ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

More about Tuckman's sequence of small group development

Reaching Agreements in Technological Contexts [December 7, 2022]

Reaching Agreements in Technological Contexts [December 7, 2022]- Reaching consensus in technological contexts presents special challenges. Problems can arise from interactions between the technological elements of the issue at hand, and the social dynamics of the group addressing that issue. Here are three examples.

The Politics of Forming Joint Leadership Teams [January 4, 2023]

The Politics of Forming Joint Leadership Teams [January 4, 2023]- Some teams, business units, or enterprises are led not by individuals, but by joint leadership teams of two or more. They face special risks that arise from both the politics of the joint leadership team and the politics of the organization hosting it.

Tuckman's Model and Joint Leadership Teams [January 18, 2023]

Tuckman's Model and Joint Leadership Teams [January 18, 2023]- Tuckman's model of the stages of group development, applied to Joint Leadership Teams, reveals characteristics of these teams that signal performance levels less than we hope for. Knowing what to avoid when we designate these teams is therefore useful.

Beating the Layoffs: II [November 20, 2024]

Beating the Layoffs: II [November 20, 2024]- If you work in an organization likely to conduct layoffs soon, keep in mind that exiting voluntarily can carry advantages. Here are some advantages that relate to collegial relationships, future interviews, health, and severance packages.

White Water Rafting as a Metaphor for Group Development [December 4, 2024]

White Water Rafting as a Metaphor for Group Development [December 4, 2024]- Tuckman's model of small group development, best known as "Forming-Storming-Norming-Performing," applies better to development of some groups than to others. We can use a metaphor to explore how the model applies to Storming in task-oriented work groups.

Subgrouping and Conway's Law [December 18, 2024]

Subgrouping and Conway's Law [December 18, 2024]- When task-oriented work groups address complex tasks, they might form subgroups to address subtasks. The structure of the subgroups and the order in which they form depend on the structure of the group's task and the sequencing of the subtasks.

The Storming Puzzle: I [December 25, 2024]

The Storming Puzzle: I [December 25, 2024]- Tuckman's model of small group development, best known as "Forming-Storming-Norming-Performing," applies to today's task-oriented work groups — if we adapt our understanding of it. If we don't adapt, the model appears to conflict with reality.

The Storming Puzzle: II [January 1, 2025]

The Storming Puzzle: II [January 1, 2025]- For some task-oriented work groups, Tuckman's model of small group development doesn't seem to fit. Storming seems to be absent, or Storming never ends. To learn how this illusion forms, look closely at Satir's Change Model and at what we call a task-oriented work group.

The Storming Puzzle: Patterns and Antipatterns [January 15, 2025]

The Storming Puzzle: Patterns and Antipatterns [January 15, 2025]- Tuckman's model of small group development, best known as "Forming-Storming-Norming-Performing," applies to today's task-oriented work groups, if we understand the six principles that govern transitions from one stage to another. Here are some examples.

Storming: Obstacle or Pathway? [January 22, 2025]

Storming: Obstacle or Pathway? [January 22, 2025]- The Storming stage of Tuckman's model of small group development is widely misunderstood. Fighting the storms, denying they exist, or bypassing them doesn't work. Letting them blow themselves out in a somewhat-controlled manner is the path to Norming and Performing.

A Framework for Safe Storming [January 29, 2025]

A Framework for Safe Storming [January 29, 2025]- The Storming stage of Tuckman's development sequence for small groups is when the group explores its frustrations and degrees of disagreement about both structure and task. Only by understanding these misalignments is reaching alignment possible. Here is a framework for this exploration.

On Shaking Things Up [February 5, 2025]

On Shaking Things Up [February 5, 2025]- Newcomers to work groups have three tasks: to meet and get to know incumbent group members; to gain their trust; and to learn about the group's task and how to contribute to accomplishing it. General skills are necessary, but specifics are most important.

On Substituting for a Star [February 12, 2025]

On Substituting for a Star [February 12, 2025]- Newcomers to work groups have three tasks: to meet and get to know incumbent group members; to gain their trust; and to learn about the group's task and how to contribute to accomplishing it. All can be difficult; all are made even more difficult when the newcomer is substituting for a star.

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Conflict Management:

When You're the Target of a Bully

When You're the Target of a Bully- Workplace bullies are probably the organization's most expensive employees. They reduce the effectiveness

not only of their targets, but also of bystanders and of the organization as a whole. What can you do

if you become a target?

Divisive Debates and Virulent Victories

Divisive Debates and Virulent Victories- When groups decide divisive issues, harmful effects can linger for weeks, months, or forever. Although

those who prevail might be ready to "move on," others might feel so alienated that they experience

even daily routine as fresh insult and disparagement. How a group handles divisive issues can determine

its success.

Dealing with Rapid-Fire Attacks

Dealing with Rapid-Fire Attacks- When a questioner repeatedly attacks someone within seconds of their starting to reply, complaining

to management about a pattern of abuse can work — if management understands abuse, and if management

wants deal with it. What if management is no help?

The Myth of Difficult People

The Myth of Difficult People- Many books and Web sites offer advice for dealing with difficult people. There are indeed some difficult

people, but are they as numerous as these books and Web sites would have us believe? I think not.

Tuckman's Model and Joint Leadership Teams

Tuckman's Model and Joint Leadership Teams- Tuckman's model of the stages of group development, applied to Joint Leadership Teams, reveals characteristics

of these teams that signal performance levels less than we hope for. Knowing what to avoid when we designate

these teams is therefore useful.

See also Conflict Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!