Until very recently, ground war tactics emphasized control of the movement of forces and materiel. In this style of conflict, the flanking maneuver is a way of cutting off access of forces to resupply, and cutting off their ability to advance or retreat. In a typical flanking maneuver, force is applied to one side of the main opposing force, or perhaps to its rear, where the opponent's forces are less well protected. By contrast, a frontal assault applies force to the strongest face of the opposing configuration.

Project plans

generally consist

solely of plans

for "frontal assaults"In project management, we also perform flanking maneuvers, but we use other names for the tactics. Military flanking maneuvers, however, are often more sophisticated than those of project managers. We can learn much from studying even basic ground tactics.

When we encounter an obstacle in a project, we have three basic choices.

- We can quit

-

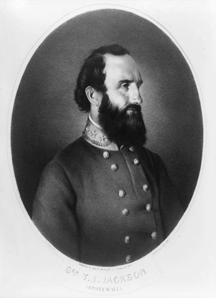

Gen. T.J. "Stonewall" Jackson executed a now-classic flanking maneuver at the Battle of Chancellorsville, during the U.S. Civil War. Photo by J.L. Giles, courtesy Prints and Photographs Division of the U.S. Library of Congress

- We can solve it

- In the military domain, we mount a frontal attack, possibly with enhanced forces. In project management, we add staff, budget or schedule.

- We can circumvent it

- In the military domain, we execute any of a variety of flanking maneuvers, or we bypass the position. In project management, we find a workaround, which might involve a redesign or using an alternative technology.

Project plans generally consist solely of plans for frontal assaults. We decide how we'll solve the problem, and we prepare a plan that implements that solution. We make few, if any, preparations for flanking maneuvers or alternatives of any kind that might be useful if we encounter obstacles. When we do, we call such plans "risk management," and too often, they're sketchy.

Military plans are usually more sophisticated. They include plans for acquiring intelligence, which is essential if adjustments are required. And they include possible adjustments too.

A more sophisticated project plan has resources allocated to three elements:

- Gathering and fusing intelligence

- Even though the plan focuses on a specific approach, we study alternative approaches right from the outset. If problems develop, we already know a fair amount about alternatives.

- Executing alternatives in parallel

- By executing at least one alternate approach in parallel, we facilitate collecting intelligence, and ensure a running start if the favored approach gets stuck. We might even provide insights that are useful in the favored approach.

- Looking far ahead

- A reconnaissance team working far ahead of the main body of the current effort searches for and provides early warning of hidden difficulty or unrecognized opportunity. If necessary, they use placeholders for yet-to-be-developed project elements.

The more expense-minded among us might resist allocating resources to these activities. Ask them this: What fraction of past projects was completed without flanking maneuvers? ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

For an overview of tactics, see "65 Operational Firepower: the Broader Stroke" by Colonel Lamar Tooke, US Army, Retired. Combined Arms Center: Military Review, July-August 2001.

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Nine Project Management Fallacies: I

Nine Project Management Fallacies: I- Most of what we know about managing projects is useful and effective, but some of what we "know"

just isn't so. Identifying the fallacies of project management reduces risk and enhances your ability

to complete projects successfully.

Design Errors and Groupthink

Design Errors and Groupthink- Design errors cause losses, lost opportunities, accidents, and injuries. Not all design errors are one-offs,

because their causes can be fundamental. Here's a first installment of an exploration of some fundamental

causes of design errors.

Unresponsive Suppliers: II

Unresponsive Suppliers: II- When a project depends on external suppliers for some tasks and materials, supplier performance can

affect our ability to meet deadlines. How can communication help us get what we need from unresponsive

suppliers?

The Planning Fallacy and Self-Interest

The Planning Fallacy and Self-Interest- A well-known cognitive bias, the planning fallacy, accounts for many unrealistic estimates of project

cost and schedule. Overruns are common. But another cognitive bias, and organizational politics, combine

with the planning fallacy to make a bad situation even worse.

Power Distance and Risk

Power Distance and Risk- Managing or responding to project risks is much easier when team culture encourages people to report

problems and to question any plans they have reason to doubt. Here are five examples that show how such

encouragement helps to manage risk.

See also Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- A common dilemma in knowledge-based organizations: ask for an explanation, or "fake it" until you can somehow figure it out. The choice between admitting your own ignorance or obscuring it can be a difficult one. It has consequences for both the choice-maker and the organization. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!