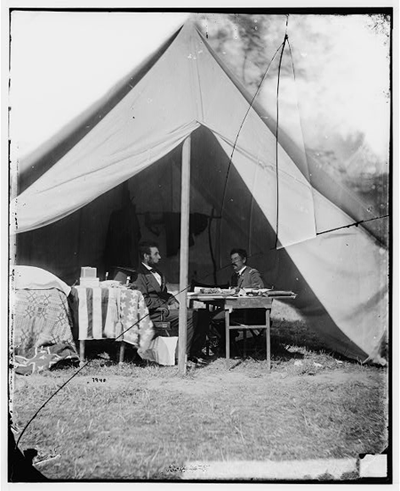

President Lincoln (left) and Gen. George B. McClellan (right) in the general's tent near the Antietam battlefield, October 3, 1862. View a larger image. Although the Battle of Antietam is regarded as a Union victory, McClellan's performance was so questionable that many believe a more effective general could have utterly destroyed Gen. Robert E. Lee's army, given the advantages Gen. McClellan had. In a truly astounding bit of luck, on September 12th, 1862, as the Union's Twelfth Army Corps bivouacked about five miles from Frederick, Maryland, Corporal Barton W. Mitchell found an envelope lying in the tall grass. It contained three cigars and a copy of Gen. Lee's battle plans. Within hours, the plans, without the cigars, were passed up the chain of command to Gen. McClellan. After assessing the plans as real, Gen. McClellan formulated and executed a response, but he did not act with urgency, nor did he communicate any sense of urgency to his subordinates. The slowness of his response enabled Gen. Lee to avoid a catastrophe. That is why this incident is used so often to demonstrate Gen. McClellan's ineffectiveness as a commander.

There is much speculation about the reasons for Gen. McClellan's unwillingness to commit forces with alacrity. One possibility is that he had a low tolerance for the unknown. In a pattern demonstrated repeatedly as a commander, he tended to wait for situations to develop, rather than act earlier in the face of uncertainty. We cannot know for certain why he moved so slowly so often, but we do know that President Lincoln found the pattern so frustrating that he eventually relieved the general of command. Photograph by Alexander Gardner, courtesy U.S. Library of Congress.

When deciding whether to adopt a goal, groups sometimes fall into destructive conflict between those who want the group to commit to the goal (the advocates) and those, less willing, who want to know more about how the group can achieve that goal (the skeptics). Because the skeptics often express their concerns by asking "How?", the debate about whether to commit to the goal can descend into inappropriate problem solving.

Here are some common reasons for the differences between advocates and skeptics.

- Tolerance for failure

- The decision to adopt the goal often requires a commitment to the goal long before a path to success becomes clear. For some, the possibility of insurmountable obstructions yet unrecognized creates internal tension. For others, trying and failing can be very costly emotionally. To reduce the tension about possible obstructions, or to limit the risk of failure, some people ask the How question.

- Tolerance for the unknown

- Even if all obstacles are eventually overcome, the cost of overcoming them, and the time required, might be unknown at the outset. Cost and schedule are just two of the unknowns. Other examples: Who do we need to help us? What do we have to learn? What resources are required?

- Tolerance for conflict

- Sometimes striving for the goal entails conflict with people. Conflict can be creative or toxic, but even if it's creative, healthy, and constructive, some people are unwilling to engage in it. Perhaps they've had experiences that suggest to them that the coming conflict will be unhealthy. In any case, some people are unwilling to commit to the goal if they anticipate conflict.

- Unfamiliarity with the problem space

- For some, general unfamiliarity with the problem space or the problem itself can be troubling. To cope with this, they seek to manage the overall risk of approaching the problem by demanding information that might not be available. If the information is forthcoming, they feel comforted. If not, they argue for rejecting the proposal.

- Hat hanging

- Some people make For some, general unfamiliarity

with the problem space or the

problem itself can

be troublingconnections — usually outside their awareness — between the current situation and some other situation they've known. If that other situation was painful or didn't turn out well, they might feel hesitant to commit to the proposed goal. This can lead them to ask the How question, demanding more details than they might otherwise require. - Toxic politics

- Some are skeptical because they see adoption as a threat to their narrow political interests. By asking the How question, and demanding clarity at a level of detail that isn't available, they hope to dissuade the group from pursuing the goal.

Advocates of the goal can experience frustration when repeatedly restrained by the skeptics. If the group can distinguish skepticism from problem solving, it can keep tension from building, and focus on Whether, instead of How. ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

For more about differences and disagreements, see "Appreciate Differences," Point Lookout for March 14, 2001; "When You Think They've Made Up Their Minds," Point Lookout for May 21, 2003; "Towards More Gracious Disagreement," Point Lookout for January 9, 2008; and "Blind Agendas," Point Lookout for September 2, 2009.

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Problem Solving and Creativity:

Design Errors and Groupthink

Design Errors and Groupthink- Design errors cause losses, lost opportunities, accidents, and injuries. Not all design errors are one-offs,

because their causes can be fundamental. Here's a first installment of an exploration of some fundamental

causes of design errors.

Rationalizing Creativity at Work: II

Rationalizing Creativity at Work: II- Creative thinking at work can be nurtured or encouraged, but not forced or compelled. Leaders who try

to compel creativity because of very real financial and schedule pressures rarely get the results they

seek. Here are examples of tactics people use in mostly-futile attempts to compel creativity.

Tackling Hard Problems: I

Tackling Hard Problems: I- Hard problems need not be big problems. Even when they're small, they can halt progress on any project.

Here's Part I of an approach to working on hard problems by breaking them down into smaller steps.

What Keeps Things the Way They Are

What Keeps Things the Way They Are- Changing processes can be challenging. Sometimes the difficulty arises from our tendency to overlook

other processes that work to keep things the way they are. If we begin by changing those "regulator

processes" the difficulty can sometimes vanish.

Why Meetings Go Down Rabbit Holes

Why Meetings Go Down Rabbit Holes- When a meeting goes "down the rabbit hole," it has swerved from the planned topic to detail-purgatory,

problem-solving hell, irrelevance, or worse. All participants, not only the Chair, contribute to the

problem. Why does this happen?

See also Problem Solving and Creativity for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!