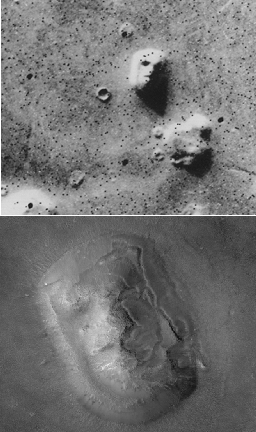

The "Face on Mars" as seen by Viking 1 in 1976 (top), compared to the Mars Global Surveyor image taken in 2001 (bottom). When the image was first released, it set off a flurry of speculation among those unaware of the dangers of apophenia or its cousin, pareidolia. The idea of a face carved on Mars by aliens took root, and even led to the release of a film, Mission to Mars, starring Tim Robbins, Gary Sinise, and Don Cheadle. To this day, the phrase face on Mars gets over 548 million hits at Google, which is most respectable for a thoroughly debunked illusion. Photos courtesy U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Viking mission and Mars Global Surveyor mission.

Let's begin our exploration of wishful thinking at the beginning, where we take in information about the world. After we receive information from the world — from our environment and from the people in it — we process that information. We can regard the early stages of that process as intake, which includes choosing where to acquire data, actually acquiring it with our sensors (eyes, ears, touch, and so on), and processing that data in the sensors, in the brain, and in the connections between sensors and brain. Because the world is so complex, we must be selective, and we can't process all the data we acquire. So we do our best. The result is inevitably an incomplete representation of the world.

And that's where things begin to get interesting.

To reduce the volume of data, we take shortcuts that introduce systematic distortions and misrepresentations. Many of these shortcuts (but not all) are among what psychologists call cognitive biases. When we want the world to be a certain way, these shortcuts and biases help us see things that way. That's how they can contribute to wishful thinking.

Here are some of the known phenomena that contribute to wishful thinking by affecting the data we take in.

- Confirmation bias

- Our preconceptions and wishes can affect how we search for information, how we process it, and how we recall it. Our wishes can even affect what questions we ask. This phenomenon is known as confirmation bias.

- Examine your research process. Did you search only for what you hoped you'd find? Or did you also ask the questions that a skeptic would have asked?

- Attentional bias

- The focus of our attention can be biased by what we've been attending to recently, by what we're familiar with, by what we like, or by what we understand most easily. Biased attention yields a distorted view of the overall situation.

- To gain insight into what you might have overlooked, consider what you've been exploring recently, your likes, your familiarities, and what you find easy to understand. That's where your wishes are. Then look elsewhere. That's where you'll find what you wish wasn't so — or what never occurred to you at all.

- Seeing patterns that aren't there

- Some cognitive Biased attention yields

a distorted view of the

overall situationbiases result in noticing patterns that don't actually exist: among them are the clustering illusion, the hot hand fallacy, pareidolia, and apophenia. [Brenner 2014] When we have wishes to be fulfilled, we're more likely to see patterns that support those wishes. - Seeing false patterns is misleading enough, but when we use them to guide us in gathering more data, the false patterns can reinforce themselves, which can make them seem even more plausible. Did you use your observations of patterns to guide you in gathering further information? Did you first verify that the patterns you saw were real?

We'll continue next time with more sources of perceptual distortion that can lead to wishful thinking. ![]() First issue in this series

First issue in this series ![]() Next issue in this series

Next issue in this series ![]() Top

Top ![]() Next Issue

Next Issue

Are your projects always (or almost always) late and over budget? Are your project teams plagued by turnover, burnout, and high defect rates? Turn your culture around. Read 52 Tips for Leaders of Project-Oriented Organizations, filled with tips and techniques for organizational leaders. Order Now!

For more about apophenia, see "Apophenia at Work," Point Lookout for March 14, 2012, and "Cognitive Biases and Influence: II," Point Lookout for July 13, 2016.

Footnotes

Your comments are welcome

Would you like to see your comments posted here? rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend me your comments by email, or by Web form.About Point Lookout

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you enjoyed it and

found it useful, and that you'll consider recommending it to a friend.

This article in its entirety was written by a human being. No machine intelligence was involved in any way.

Point Lookout is a free weekly email newsletter. Browse the archive of past issues. Subscribe for free.

Support Point Lookout by joining the Friends of Point Lookout, as an individual or as an organization.

Do you face a complex interpersonal situation? Send it in, anonymously if you like, and I'll give you my two cents.

Related articles

More articles on Project Management:

Resuming Projects: Team Morale

Resuming Projects: Team Morale- Sometimes we cancel a project because of budgetary constraints. We reallocate its resources and scatter

its people, and we tell ourselves that the project is on hold. But resuming is often riskier, more difficult

and more expensive than we hoped. Here are some reasons why.

The Politics of Lessons Learned

The Politics of Lessons Learned- Many organizations gather lessons learned — or at least, they believe they do. Mastering the political

subtleties of lessons learned efforts enhances results.

Why Do Business Fads Form?

Why Do Business Fads Form?- The rise of a business fad is due to the actions of both its advocates and adopters. Understanding the

interplay between them is essential for successful resistance.

Scope Creep, Hot Hands, and the Illusion of Control

Scope Creep, Hot Hands, and the Illusion of Control- Despite our awareness of scope creep's dangerous effects on projects and other efforts, we seem unable

to prevent it. Two cognitive biases — the "hot hand fallacy" and "the illusion

of control" — might provide explanations.

Joint Leadership Teams: Risks

Joint Leadership Teams: Risks- Some teams, business units, or enterprises are led not by individuals, but by joint leadership teams

of two or more. They face special risks that arise from the organizations that host them, from the teams

they lead, or from within the joint leadership team itself.

See also Project Management for more related articles.

Forthcoming issues of Point Lookout

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance

Coming October 1: On the Risks of Obscuring Ignorance- When people hide their ignorance of concepts fundamental to understanding the issues at hand, they expose their teams and organizations to a risk of making wrong decisions. The organizational costs of the consequences of those decisions can be unlimited. Available here and by RSS on October 1.

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying

And on October 8: Responding to Workplace Bullying- Effective responses to bullying sometimes include "pushback tactics" that can deter perpetrators from further bullying. Because perpetrators use some of these same tactics, some people have difficulty employing them. But the need is real. Pushing back works. Available here and by RSS on October 8.

Coaching services

I offer email and telephone coaching at both corporate and individual rates. Contact Rick for details at rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.com or (650) 787-6475, or toll-free in the continental US at (866) 378-5470.

Get the ebook!

Past issues of Point Lookout are available in six ebooks:

- Get 2001-2 in Geese Don't Land on Twigs (PDF, )

- Get 2003-4 in Why Dogs Wag (PDF, )

- Get 2005-6 in Loopy Things We Do (PDF, )

- Get 2007-8 in Things We Believe That Maybe Aren't So True (PDF, )

- Get 2009-10 in The Questions Not Asked (PDF, )

- Get all of the first twelve years (2001-2012) in The Collected Issues of Point Lookout (PDF, )

Are you a writer, editor or publisher on deadline? Are you looking for an article that will get people talking and get compliments flying your way? You can have 500-1000 words in your inbox in one hour. License any article from this Web site. More info

Follow Rick

Recommend this issue to a friend

Send an email message to a friend

rbrenaXXxGCwVgbgLZDuRner@ChacDjdMAATPdDNJnrSwoCanyon.comSend a message to Rick

![]() A Tip A Day feed

A Tip A Day feed

![]() Point Lookout weekly feed

Point Lookout weekly feed

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!

My blog, Technical Debt for Policymakers, offers

resources, insights, and conversations of interest to policymakers who are concerned with managing

technical debt within their organizations. Get the millstone of technical debt off the neck of your

organization!